Excerpted from “The Banjo Entertainers, Roots to Ragtime, A Banjo History,” by Lowell H. Schreyer, Minnesota Heritage Publishing, 2007, pages 5-36.

The James River valley of Virginia was a locale of banjo activity in the early 1800s.

That river led to the city of Lynchburg. Only 25 miles away was the Clover Hill community in Buckingham County, part of which would become Appomattox County. Nearby was the Flood family plantation. A white neighbor boy would come over to play with young blacks on that plantation. Eventually he learned something about the peculiar instrument they played.

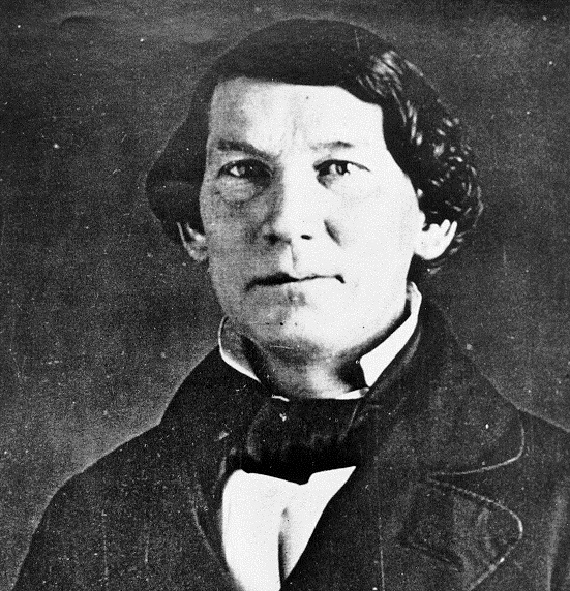

The instrument was the gourd banjo. The boy was Joel Walker Sweeney.

“I have often heard it said that… he was taught to play by a negro…,” wrote a Sweeney family acquaintance commenting on Joel Sweeney.

When Sweeney took up the banjo it was already well known as an instrument played by blacks in the area, according to P.C. Sutphin, another contemporary observer.

Sutphin also recalled Sweeney’s proficiency as a violinist. “He was an expert violinist,” he related, “and the last time I saw him, he was chief violinist at a special dance party of some of the ‘elite’ of Lynchburg.”

”When 21 years of age, he commenced the work of his life by attending the County Courts of the adjoining Counties and giving concerts at night in such vacant rooms as he could secure…,” continued Pore. “When I was but a child I saw much of Old Band Joe, as I lived but a mile from his home and had to pass his house going to and from the P.O.”

While Sweeney cannot be said to be the inventor of the banjo, as his theatrical billing sometimes proclaimed, he can certainly be recognized as the individual who popularized it in its five-string form with the general public. He can also be credited with starting a repertoire of music for the African-originated instrument by transferring to it music characteristic of a European idiom from his background as a violinist. This pattern of integrating elements of African and European music continued well into the next century in shaping American music.

Before Sweeney’s arrival on the banjo scene, the hide-covered instrument was usually described as having a gourd body. Once Sweeney became prominent, the gourd was generally replaced, except in some southeastern mountain areas, by a wooden shell for the banjo’s sounding chamber. He obviously used the wood shaping skills learned from his wheel-making father, John Sweeney, in constructing these non-gourd bodies for his banjos. The wooden rim of the body had the advantages of durability, uniformity, and availability without having to wait on a gourd-growing season.

“As his fame spread, demands were made on him from every direction and he decided to devote his whole time to giving concerts,” Pore wrote. “Up to this time he had no assistant but gave the entire entertainment himself, singing, dancing and playing different instruments; he was adept in constructing a doggerel verse and rarely appeared before an audience that he did not have a song of his own composing, (both words and music) filled with local hits.”

Johnnie Reb (Col. Stephen Farrar), who as a boy had learned to play banjo from Sweeney, also described the Virginia banjoist’s act. “One of his performances always excited to applause,” he wrote in a later newspaper account. “His old Virginia break-down, a jig tune, he danced, and made his own music with his banjo hung around his neck with a string.”

While unresolved points remain on Sweeney’s improvements to the banjo, his greater importance lay in his role of making the white mainstream of American society aware of the entertainment potential of a slaves’ instrument. Sweeney’s influence on other traveling performers who took up the banjo after hearing him play caused the instrument’s popularity to mushroom rapidly around the developing United States and abroad. Before 1836, mentions of banjo players were absent from theatrical advertising. A decade later, banjoists were a routine part of stage and circus entertainments. The change was triggered by Sweeney. He may not have been the only white man to play the banjo in the early 1800s, but he was the only one to make such an impact on American culture.

Without a doubt, Sweeney was, in theatrical terms, “a ham,” much to the banjo’s benefit. The congenial Sweeney had personality traits that made him well liked by his audiences and contributed to his success in show business.

News accounts on Sweeney also carried descriptive phrases such as “the irresistible Extravaganza singer,” “good natured countenance,” “the laughter-provoking Sweeny,” “a fine noble hearted fellow.”

Sweeney was then on his way, leaving his home state to carry the banjo sound to other parts of the nation and, eventually to Europe.

The old Virginny banjoist opted for the theatrical glory of touring the British Isles at the height of his career as the leading banjoist in America.

Joel Sweeney’s sailing away to Europe did not remove the sound of the banjo from American theaters. Prior to leaving for England, he had planted sufficient seeds for banjo growth that ensured the continuation of the instrument’s popularity in this country…

Sweeney, meanwhile, remained in the British Isles until 1845 inspiring more potential banjo players and instilling in the British cousins a love of the instrument that exists to this day. Strangely, his amiable nature in getting other performers started on the banjo in America went into complete reversal in Great Britain. Probably protecting his exclusive position on an instrument supposedly new to that country, he became very secretive about anyone examining and copying his banjo off stage.

By the time Sweeney returned from England in 1845, other entertainers, in addition to Billy Whitlock, had taken his place in spreading the popularity of the banjo as a performing musical instrument across the United States.

Within one decade, the banjo had become an important part of the entertainment field. The banjo had developed from a homemade to a commercially constructed instrument, and formal banjo instruction had become available. It was just the beginning. A lot of history for the instrument and its players lay ahead.