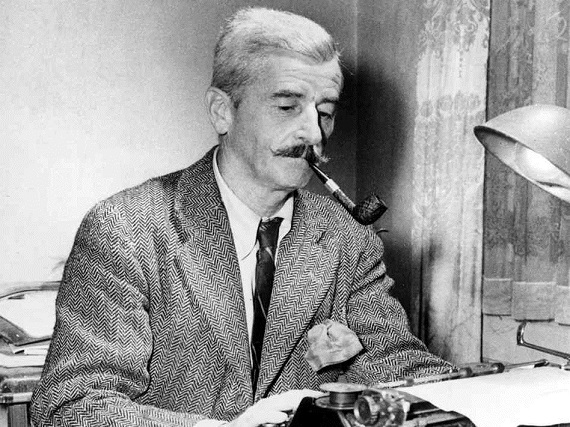

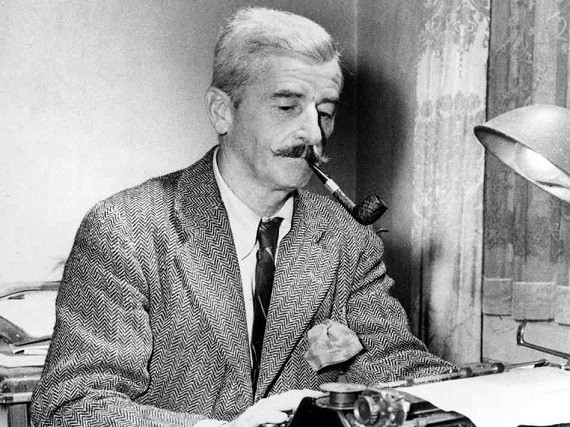

William Faulkner of Mississippi was the greatest writer produced by the United States in the 20th century. His craft was fiction, but like any great writer he was a better historian and philosopher than most who wear those labels . I was reminded of a nonfiction piece of Faulkner’s recently when the hoopla erupted about some of the pampered and petted gladiators of the commercial sports industry trashing the national anthem. This article was Faulkner’s sole contribution to Sports Illustrated (January 1955) and was called “An Innocent at Ringside.”

In this essay Faulkner writes about his first viewing of an ice hockey match, which he describes beautifully and inimitably. Then he reflects on the preoccupation of Americans with sports spectacles, viewed while sitting in rain-proofed and often cold-proofed comfort, in comparison with our ancestors’ hunting, fishing, sailing. He (in the role of Innocent) wondered:

“just what a professional hockey-match, whose purpose is to make a decent and reasonable profit for its owners, had to do with our National Anthem. What are we afraid of? Is it our national character of which we are so in doubt, so fearful that it might not hold up in the clutch, that we not only dare not open a professional athletic contest or a beauty-pageant or a real-estate auction, but we must even use a Chamber of Commerce race for Miss Sewage Disposal or a wildcat land-sale, to remind us that that liberty gained without honor and sacrifice and held without constant vigilance and undiminished honor and complete willingness to sacrifice at need, was not worth having to begin with?”

Faulkner suggests that the need to blare out the anthem at every occasion reflects a dream-like state of denial, a cover-up for a loss of the real patriotism and courage of our forebears. This loss of human quality and purpose in the trivial and materialistic America of the Fifties was a theme repeated in various writings of his later years. In fact, when he passed away in 1962 Faulkner was working on a book to be called “The American Dream—What Happened to It?”

If there is some truth in the great observer’s view, then the gladiators’ refusal to stand for the anthem is just imposing one phony gesture on top of another. Why do Americans need this ritual at sports contests? And why does our society award wealth and adulation to athletes to the extent that we should care what they think? Athletic prowess attracts natural admiration, but such skills pursued exclusively are of very limited social usefulness. Unless governed by character they can become, indeed, social deficits. George Washington was a great horseman, but that is not the reason he was first in the hearts of his countrymen. Athlete-worship indicates that a large portion of the American public suffers from arrested adolescence, which disqualifies them for real citizenship, and points at a bit of imperial Roman decadence.

And what about this national anthem of the star-spangled banner? It has often been observed that it is not particularly inspiring, unlike other national anthems like “Dixie” and “The Marsellaise.” The undistinguished music comes from some European tune or other about “Anacreon.” As is well-known, the words were written by Francis Scott Key. Key watched while a British fleet bombarded Fort McHenry in Baltimore Harbor during the War of 1812. The Fort, a vital part of the defenses of one of America’s largest cities, held. Key was inspired to verse by the sight of the starry banner of the Union still flying after the attack.

Here is a part of the story not known. Francis Key Howard was Key’s grandson, and also the grandson of Col. John Eager Howard, Maryland’s foremost soldier in the Revolution. In September 1861 Francis Key Howard was held as a prisoner of the U.S. Army in that same Fort McHenry. He had been seized without warrant because of a newspaper editorial he had written criticising Abraham Lincoln for his suspension of the right of habeas corpus. (The Chief Justice of the United States had already declared Lincoln’s action illegal.) Lincoln’s army had seized and imprisoned the mayor, city council, and police commissioners of Baltimore, along with a Maryland Congressman and other citizens.

Howard had this to say about his prison experience:

“When I looked out in the morning, I could not help being struck by an odd and not unpleasant coincidence. On that day forty-seven years before, my grandfather . . . had witnessed the bombardment of Fort McHenry. . . . he wrote the song so long popular throughout the country, the Star Spangled Banner. As I stood upon the very scene of that conflict, I could not but contrast my position with his, forty-seven years before. The flag which he had then so proudly hailed, I saw waving over the same place over the victims of as vulgar and brutal a despotism as modern times have witnessed.”

After Lincoln had launched his ruthless war of invasion and conquest against fourteen States and their citizens, the song and the flag which it celebrates represented something quite other than what Francis Scott Key had in mind. They now stood for a supreme power in Washington rather than a patriotic Union. (The stars, remember, represent States.) The “Star-Spangled Banner” was captured property, appropriated for a phony national history. Yet another layer of unreality for that national anthem. Like putting the Southern republican statesmen Washington and Jefferson (more captured Southern property), on Mount Rushmore along with the blood-and-iron nationalists Lincoln and Theodore Roosevelt.

Officially-decreed national anthems are a product of 20th century militarism. Note that Howard refers to “The Star-Spangled Banner” as a popular song. It was used in a celebratory manner, along with other songs, not officially. National anthems and national flags before the 20th century were strongly associated with armies and navies and not seen or heard very often by ordinary citizens. The song was not made an official “national” anthem until 1931! You might say that it represents the idea that all of us are potential cannon fodder for the power in Washington. That was not our forebears conception of patriotism. For them patriotism was a willing defense of one’s people, not being an obedient and conscriptable government asset.

The official national anthem and the Pledge of Allegiance are symbols that we are no longer free men but property of the government. The ugly history of the fascist Pledge of Allegiance has been pointed out by several writers. It was invented in the early 20th century by Francis Bellamy, a “Christian Socialist” and advocate of compulsory and uniform government schooling. It represents the old New England Yankee drive for dominance and was intended particularly to combat the fear of people like Bellamy that immigrants would escape their control. Almost nobody knows that the Pledge made its first appearance with right arm raised and extended—the fascist salute—which tells something about its family resemblance. The Pledge did not become official until 1942. And not until 1954 were the words “under God” added by the lobbying of a Catholic group.

Myself, I will stand during the Pledge out of politeness to the as-yet unenlightened. No repeating the words or hands over the heart. Like our forebears, I do not owe unquestioning allegiance to a flag or a government and will not swear such. Like them, I will swear to “uphold the Constitution,” which is what free men reasonably ought to do.

(More about Faulkner’s view of his own times can be found in Essays, Speeches, and Public Letters of William Faulkner, ed. By James B. Meriwether. See also “Citizen Faulkner: ‘What We Did in Those Old Days’,” in Brion McClanahan and Clyde N. Wilson, Forgotten Conservatives in American History.)