‘If only I can restore to our institutions their primitive simplicity and purity, can only succeed in banishing those extraneous corrupting influences which tend to fasten monopoly and aristocracy on the Constitution and to make the government an engine of oppression to the people instead of the agent of their will, I may then look back on the honors conferred on me with just pride – with the consciousness that they have not been bestowed altogether in vain.’

‘The preservation of the Union is the supreme law.’

‘Circumstances that cannot be controlled, and which are beyond the reach of human laws, render it impossible that you can flourish in the midst of a civilized community. You have but one remedy within your reach. And that is, to remove to the West and join your countrymen, who are already established there.’

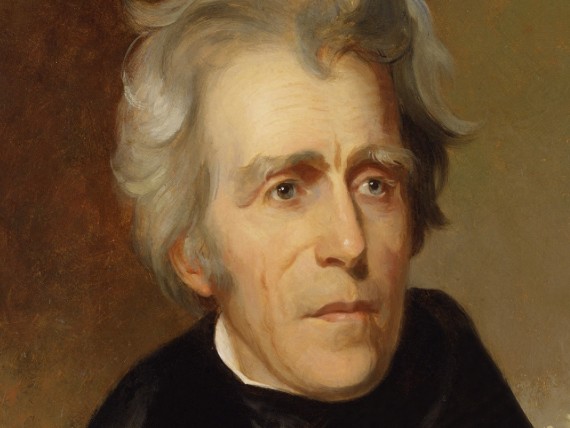

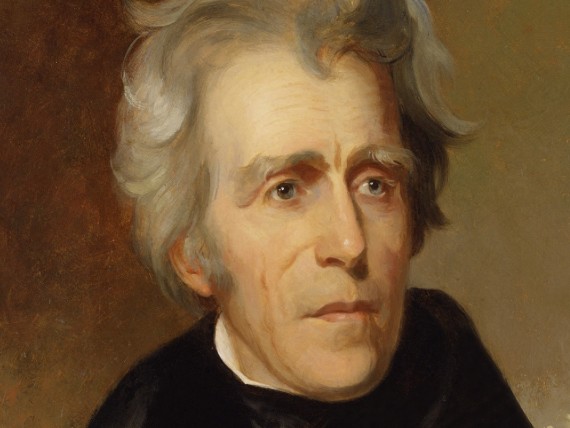

Andrew Jackson lived a truly epic life. Born to hardy Scotch-Irish stock in the Waxhaws, a backcountry region in the then-disputed border between the Carolinas, the boy Jackson became a man in the brutal guerrilla warfare between the British, the Tories, and the Patriots. Jackson joined the local militia as a courier, and when captured by the British was scarred by the sabre of a haughty officer. His father having died before he was born, his mother dead from cholera contracted treating wounded soldiers, and his two brothers dead from battle and a diseased British prison, Jackson came out of the American Revolution an orphan. By drastically staking his life, fortune, and sacred honour on battles, horse races, and duels, Jackson rose from his humble beginnings to become the victor of the Battle of New Orleans and ultimately President of the United States. His name defines an entire age of American history – ‘The Age of Jackson’ – and ‘Jacksonian democracy’ is a term still used today to describe a sort of libertarian egalitarianism or populist Jeffersonianism.

Despite his significance and popularity, Andrew Jackson has not escaped the ire of the American jihadists wantonly purging American history in accord with present social sensibilities. Indeed, a growing number of Americans want to chop Old Hickory off the twenty-dollar bill (an ironic insult, given Jackson’s opposition to a national bank). In a typical attack, Slate Magazine accuses Jackson of having ‘engineered genocide’ of the Indians and concludes that ‘he should be vilified, not honored.’

The mission of the Abbeville Institute is ‘to preserve what is true and valuable in the Southern tradition.’ How should Americans, then, and especially American Southerners, view Andrew Jackson? What is the good, the bad, and the ugly of this easy-to-hate Southerner?

The Good

In the presidential election of 1824, the ‘outsider’ Andrew Jackson received a plurality of the popular and electoral vote against the ‘establishment’ candidates of John Quincy Adams (the son of John Adams) and John H. Crawford (the heir apparent of the Jefferson-Madison-Monroe Virginia Dynasty), but not the majority necessary to win election. As a result, the election transferred to the House of Representatives, where Quincy Adams won the election in what was perceived by many, Jackson included, as a ‘corrupt bargain’ between him and Speaker of the House Henry Clay, who was shortly thereafter appointed as Secretary of State. Earlier, when some of Clay’s ‘friends’ approached Jackson with an offer of Clay’s support in exchange for assurances that he would not appoint Quincy Adams as Secretary of State, Jackson replied, ‘Say to Mr. Clay and his friends that before I would reach the presidential chair by such means…I would see the earth open and swallow both Mr. Clay and his friends and myself with them.’

President Quincy Adams embarked on an unpopular and unconstitutional neo-Federalist agenda of national economic planning. Aware that public opinion would be negative, the elitist Quincy Adams went so far as to urge Congressmen to ignore their constituents and support his expensive proposals. This was such an alarming turn of events that the aged Thomas Jefferson wrote the ‘Solemn Declaration and Protest’ for Virginia, denouncing Quincy Adam’s ‘usurpations’ and warning that the only evil worse than a ‘separation in the Union was ‘submission to a government of unlimited powers.’ Vice President John C. Calhoun of South Carolina (who, as the editor of his papers, Clyde N. Wilson, quips, was the one Vice President who was important not because he was Vice President, but was Vice President because he was important), the wily Senator Martin Van Buren of New York, and other Jeffersonian public figures organised the political opposition against Quincy Adams, which coalesced around the figure of Andrew Jackson and ultimately became the Democratic Party.

In 1828, Andrew Jackson defeated Quincy Adams for the presidency. Before Jackson, political parties controulled presidential elections. Party caucuses nominated candidates among the party elite, largely comprised of propertied and educated gentry. Campaigns were conducted on the pages of party newspapers and in letters between party members. Jackson, however, was the first popularly elected President. Jackson’s legacy of opening up of politics to the plain folk, however, also entailed the dumbing down of politics. For instance, a popular Jacksonian campaign slogan was, ‘John Quincy Adams who can write, Andrew Jackson who can fight!’ (the implication being that Quincy Adams, the son of a Founding Father who grew up in the American diplomatic service, attended Harvard University, knew the Tsar personally, and was a successful Secretary of State, was inferior to Jackson, who had fought the Indians and the British).

Andrew Jackson aimed to reestablish the Jeffersonian ideal of ‘that government which governs best governs least,’ which had been lost in the ‘corrupt bargain’ and neo-Federalist agenda of John Quincy Adams and Henry Clay. In his First Inaugural Address, Jackson explained his philosophy of good governance: ‘As long as our government is administered for the good of the people, and is regulated by their will; as long as it secures to us the rights of person and of property, liberty of conscience and of the press, it will be worth defending.’ According to Jackson, ‘equality among the people in the rights conferred by government’ was the ‘great radical principle of freedom.’ Jackson viewed himself as the champion of the ‘great body of the citizens’ against special interests such as industrialists and financiers, which he regarded as ‘the predatory portion of the community.’ As President, Jackson upheld his standards, cutting taxes and spending, balancing the budget and distributing the surplus among the States, repaying the national debt in its entirety, and investigating corruption and waste in executive departments.

Andrew Jackson is most famous for, as he put it, having ‘killed the bank,’ a ‘hydra of corruption.’ Early in his presidency, Jackson had reached an accommodation with Nicholas Biddle, the President of the Second Bank of the United States, agreeing to certain reforms to restrict the political activities of the bank. When Biddle went behind Jackson’s back with presidential aspirant Henry Clay, however, and attempted to recharter the bank without the reforms to which they had earlier agreed, Jackson, incensed against Clay and Biddle, went to ‘war’ against the bank.

In his veto message for the recharter bill, Andrew Jackson declared that he was ‘deeply impressed with the belief that some of the powers and privileges possessed by the existing bank are unauthorized by the Constitution, subversive of the rights of the States, and dangerous to the liberties of the people.’ Specifically, Jackson was suspicious of the bank’s powers to inflate or deflate the currency at will, redistribute wealth from Southern and Western plain folk to a Northern and foreign financial elite, and corrupt the Congress and the press with easy money. Jackson flatly rejected the claim that the Supreme Court had ‘settled’ the constitutionality of a national bank, arguing that the Congress and the President were ‘coordinate authorities’ with the Supreme Court. ‘Each public officer who takes an oath to support the Constitution swears that he will support it as he understands it, and not as it is understood by others,’ explained Jackson. ‘The authority of the Supreme Court must not, therefore, be permitted to control the Congress or the Executive when acting in their legislative capacities, but to have only such influence as the force of their reasoning may deserve.’ While previous Presidents had deferred to George Washington’s rule of limiting his judgment of a bill to its constitutionality, Jackson cited social and economic reasons for vetoing the recharter bill:

It is to be regretted that the rich and powerful too often bend the acts of government to their selfish purposes. Distinctions in society will always exist under every just government. Equality of talents, of education, or of wealth can not be produced by human institutions. In the full enjoyment of the gifts of Heaven and the fruits of superior industry, economy, and virtue, every man is equally entitled to protection by law; but when the laws undertake to add to these natural and just advantages artificial distinctions, to grant titles, gratuities, and exclusive privileges, to make the rich richer and the potent more powerful, the humble members of society – the farmers, mechanics, and laborers – who have neither the time nor the means of securing like favors to themselves, have a right to complain of the injustice of their Government. There are no necessary evils in government. Its evils exist only in its abuses. If it would confine itself to equal protection, and, as Heaven does its rains, shower its favors alike on the high and the low, the rich and the poor, it would be an unqualified blessing. In the act before me there seems to be a wide and unnecessary departure from these just principles.

In the ensuing ‘bank war,’ Andrew Jackson withdrew federal funds from the Second Bank of the United States and deposited them in State-chartered banks. Until the bank’s charter expired, however, the Second Bank of the United States was the legal depository of federal funds. Jackson had to remove and replace two Treasury Secretaries before he found one who would comply with his command – Roger B. Taney, whom he would reward with an appointment as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. At the same time, many of these State-chartered banks were controulled by Jacksonians, leading to the derisive term ‘pet banks.’ Jackson’s critics claimed that Jackson was an American Caesar, riding roughshod over the law under the pretense of saving the republic. John C. Calhoun, who had resigned as Vice President and been elected as a South Carolina Senator, denied that the issue was ‘bank or no bank,’ for he was against the bank himself, but was rather the ‘union of the banking system with the executive.’ Jackson, however, convinced of the bank’s corruption and consumed with hatred of Nicholas Biddle (whose strategy of pressuring Jackson by contracting credit only reinforced Jackson’s opposition to the bank), was adamant. ‘You are den of vipers and thieves!’ Jackson bellowed at a group of bank petitioners, banging his fist down on the table. ‘I have determined to rout you out, and by the Eternal, I will rout you out!’

A struggle between ‘liberty and power’ defined the Age of Jackson. In this struggle, Andrew Jackson succeeded striking a blow for liberty – downsizing the oversized federal government, checking an arrogant Supreme Court, and abolishing the corrupt Second Bank of the United States. Yet Jackson’s victory for liberty resorted to tactics which weakened the rule of law and aggrandised the presidency over the legislature, the judiciary, and the States. Indeed, Jackson transformed the American presidency from the traditional role of ‘First Magistrate of the United States’ to, as he put it, ‘the direct representative of the people’ – a powerful national leader rather than a humble public servant. Prior to Jackson, the Congress had been the dominant branch in Washington, D.C., but after Jackson, it was the President who controulled not just his party but the government itself. When Jackson was first approached with the prospect of the presidency, he himself acknowledged that he was not suited to the position. ‘Do they think that I am such a damned fool to think myself fit for President of the United States?’ he exclaimed. ‘No, sir; I know what I am fit for. I can command a body of men in a rough way, but I am not fit to be President.’ What this old military man meant became painfully clear when he was faced with a challenge to his authority.

The Bad

In 1828, Jacksonians in the Congress passed the heaviest protectionist tariff in American history. The Jacksonians figured that this tariff raised rates so high that President John Quincy Adams would have no choice but to veto the bill, giving Andrew Jackson an issue to exploit in the North (where industrial protectionism was popular and where the Southern war hero had the least support). Virginia Congressman John Randolph of Roanoke, that old-school Virginian and eccentric aristocrat-libertarian, sneered at his colleagues’ cynical ruse, pithily remarking, ‘The bill referred to manufactures of no sort or kind, but the manufacture of a President of the United States.’ In the end, the Jacksonians were hoisted on their own petard when Quincy Adams signed the bill anyway. The agricultural, commercial South, where tariffs on imported manufactures fell hardest, was outraged. Maryland Senator Samuel Smith, a veteran of the War of American Independence and War of 1812, branded the tax ‘the Tariff of Abominations,’ a name which stuck among Southerners.

South Carolina smoldered with hatred of the Tariff of Abominations and fear of Southern enslavement to the North. South Carolinians had counted the votes and realised that even if the South were united in the Congress, she could not stop the North from taxing the South and spending on herself. Congressman George McDuffie was spreading his ‘Forty Bale Theory,’ which held that for every one-hundred bales of cotton that South Carolinians raised, forty were paid to the North in taxes. Thomas Cooper, President of the South Carolina College, urged South Carolinians to ‘calculate the value of the Union…by which the South has always been the loser and the North always the gainer.’ Robert J. Turnbull, writing under the pseudonym Brutus, warned in his pamphlet, The Crisis, ‘The GREAT SOUTHERN GOOSE will yet bear more plucking.’ Congressman Robert B. Rhett, in a pair of resolutions from his district, denounced the ‘oppressive,’ ‘unconstitutional,’ and ‘tributary’ Tariff of Abominations, and declared that ‘our attachment to this Union can only be limited by our superior attachment to our rights.’ South Carolina Senator Robert Y. Hayne, in response to Massachusetts Senator Daniel Webster’s declamation of ‘Liberty and Union, now and forever, one and inseparable,’ countered with ‘Liberty – the Constitution – Union.’ When President Andrew Jackson, at a Democratic celebration of Thomas Jefferson’s birthday, toasted, ‘The Union: it must be preserved,’ Vice President John C. Calhoun toasted in reply, ‘The Union: next to our Liberty, the most dear!’

In 1828, shortly after the Tariff of Abominations was enacted into law, John C. Calhoun authored the Exposition and Protest, a lengthy disquisition on economics and politics adopted by the South Carolina legislature. In the Exposition and Protest, Calhoun sought to develop a way for the States to carry out the ‘Principles of ’98’ enunciated by James Madison and Thomas Jefferson in the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions. The Tariff of Abominations, began Calhoun, was unequal in its economic effects (enriching the North at the expense of the South) and unconstitutional in its intent (promoting special interests rather than the general welfare). As one of the sovereign parties to the constitutional compact, Calhoun continued, the State of South Carolina had the right to ‘nullify’ such a law – meaning to declare it unenforceable within her jurisdiction and call for a convention of States to resolve the dispute. According to Calhoun, carrying out Jefferson and Madison’s ‘rightful remedy’ was ‘a sacred duty to the Union, to the cause of liberty over the world,’ and South Carolinians would be ‘unworthy of the name of freemen, of Americans – of Carolinians, if danger, however great, could cause them to shrink from the maintenance of their constitutional rights.’ In 1832, when federal tariffs on key articles were further raised, South Carolina followed through on the Exposition and Protest, calling a convention and nullifying the tariffs of 1828 and 1832.

The crisis clearly called for compromise. Indeed, the Union had been built on compromise: it was compromise between the States – large versus small, Northern versus Southern, etc. – which had been the basis of the Constitution. As John Randolph of Roanoke put it, ‘Our Constitution is an affair of compromise between the States, and this is the master-key which unlocks all difficulties.’ The Union had also been built on nullification. In the 1760s and 1770s, the Colonies repeatedly nullified unconstitutional British taxes, forcing concessions of policy if not principle out of the Parliament. In 1791, Georgia nullified an unconstitutional Supreme Court ruling and was vindicated by a constitutional amendment which upheld her position. In 1798, Virginia and Kentucky nullified the unconstitutional Alien and Sedition Acts, leading to the downfall of the Federalist Party and the triumph of the Jeffersonian Democratic-Republicans. In 1809, Massachusetts and Connecticut had nullified an unconstitutional trade embargo that was shortly thereafter repealed. Whenever nullification had been tried, it had succeeded, and Americans were freer as a result.

President Andrew Jackson, however, was utterly uncompromising. During the Creek War, when his troops decided to desert, Jackson rode out in front of them and threatened, ‘I’ll shoot dead the first man who makes a move to leave!’ Jackson was to employ the same tactics against South Carolina, treating a member of a federal republic with fair grievances like he would an insubordinate soldier under his command. In his ‘Nullification Proclamation,’ Jackson rejected any compromise on the issues of tariffs or States’ rights. Jackson proclaimed, ‘I consider…the power to annul a law of the United States, assumed by one State, incompatible with the existence of the Union, contradicted expressly by the letter of the Constitution, unauthorized by its spirit, inconsistent with every principle on which it was founded, and destructive of the great object for which it was formed.’ Yet James Madison and Thomas Jefferson, in the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions, believed otherwise:

This Assembly doth explicitly and peremptorily declare, that it views the powers of the federal government, as resulting from the compact, to which the States are parties; as limited by the plain sense and intention of the instrument constituting the compact; as no further valid that they are authorized by the grants enumerated in that compact; and that in case of a deliberate, palpable, and dangerous exercise of other powers, not granted by the said compact, the States who are parties thereto, have the right, and are in duty bound, to interpose for arresting the progress of the evil, and for maintaining within their respective limits, the authorities, rights and liberties appertaining to them. – Virginia (Madison)

Resolved, that the several States composing, the United States of America, are not united on the principle of unlimited submission to their general government; but that, by a compact under the style and title of a Constitution for the United States, and of amendments thereto, they constituted a general government for special purposes – delegated to that government certain definite powers, reserving, each State to itself, the residuary mass of right to their own self-government; and that whensoever the general government assumes undelegated powers, its acts are unauthoritative, void, and of no force; that to this compact each State acceded as a State, and is an integral part, its co-States forming, as to itself, the other party: that the government created by this compact was not made the exclusive or final judge of the extent of the powers delegated to itself; since that would hae made its discretion, and not the Constitution, the measure of its powers; but that, as in all other cases of compact among powers having no common judge, each party has an equal right to judge for itself, as well of infractions as of the mode and measure of redress. – Kentucky (Jefferson)

Jackson also proclaimed, ‘Each State having expressly parted with so many powers as to constitute jointly with the other States a single nation, cannot from that period possess any right to secede, because such secession does not break a league, but destroys the unity of a nation, and any injury to that unity is not only a breach which would result from the contravention of a compact, but it is an offense against the whole Union.’ Yet Thomas Jefferson had written to James Madison in 1798 that Virginia and Kentucky should ‘sever ourselves from that Union we so much value, rather than give up the rights of self-government which we have reserved, and in which alone we see liberty, safety, and happiness,’ and to the soon-to-be Governor of Virginia in 1825 that Virginia should ‘separate from our companions only when the sole alternatives left are a dissolution of our Union with them, or submission to a government without limitation of powers.’ The States, as Jackson would learn, were not conquered Indian tribes which he could so easily overawe.

Jackson’s proclamation was hailed – and, in fact, is still hailed – for denying the ‘treason and insurrection’ of nullification and secession, but it spelled doom for the Founding Fathers’ federal republic and gave birth to the national empire that Abraham Lincoln would ultimately baptise in more blood than has been spilled in all other American wars combined. John C. Calhoun, who more than any other man of his day saw the writing on the wall, described this new Union as a government ‘sustained by force instead of patriotism.’ Indeed, Jackson’s proclamation was one of the few documents to which Lincoln referred in composing his First Inaugural Address declaring the Union indissoluble, secession treason, and civil war imminent.

As the date on which South Carolina’s nullification ordinance was to take effect approached, Andrew Jackson requested the Congress to authorise him to use military force to collect the tariff in South Carolina. ‘I will meet it at the threshold, and have the leaders arrested and arraigned for treason,’ boasted President Jackson. ‘In forty days I can have within the limits of South Carolina fifty thousand men, and in forty days more another fifty thousand.’ Jackson singled out the nullification leader, John C. Calhoun, who had resigned as Vice President and been elected Senator to represent South Carolina in the crisis, threatening that he would ‘hang him as high as Haman.’ Unsurprisingly, Jackson’s Force Bill only escalated the conflict, compelling the Governor of Virginia to pledge to the Governor of South Carolina that the Old Dominion would defend the Palmetto in any attempted invasion. ‘If South Carolina be put down then may each of the States yield all pretensions to sovereignty,’ warned Virginia Senator John Tyler, Calhoun’s sole ally in the Congress. ‘How idle to talk of preserving the republic for any length of time with an uncontrolled power over the military, exercised at the pleasure of the President.’ John Randolph of Roanoke, a feeble old man at this point, wished for his ‘dying body’ to be strapped to his horse, ‘Radical,’ and be sent into battle against ‘our Djezzar Pacha’ and his ‘ferocious and bloodthirsty proclamation.’

Andrew Jackson claimed that he was obligated ‘to execute the law’ and ‘to preserve the Union’ even if it meant ‘a recourse to force’ and ‘the shedding of a brother’s blood.’ Yet even Alexander Hamilton, a militarist, mercantilist, and monarchist, admitted at the New York Ratification Convention in 1788 that the federal government would not have the power to use force against a State. ‘To coerce the States is one of the maddest projects ever devised,’ remarked Hamilton. ‘Can any reasonable man be well-disposed toward a government which makes war and carnage the only means of supporting itself – a government that can exist only by the sword?’ As John C. Calhoun put it, ‘Force may, indeed, hold the parts together, but such union would be the bond between master and slave – a union of exaction on one side and unqualified obedience on the other.’

In the end, an eleventh-hour compromise between Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun reducing federal tariff rates in exchange for the repeal of South Carolina’s nullification ordinance averted civil war – no thanks to Andrew Jackson. Indeed, Jackson later admitted that the two chief regrets of his presidency were that he did not ‘shoot Henry Clay’ and ‘hang John C. Calhoun.’

In his violent opposition to nullification, Andrew Jackson was blinded by his hatred for John C. Calhoun, whom he distrusted and despised for perceived personal disloyalty. In other cases, Jackson was quite willing to allow and even affirm nullification.

The Ugly

In 1788, Andrew Jackson moved to Nashville, Tennessee, where he began as a lowly lawyer but rose to become a respected judge and planter, a delegate to the Tennessee Constitutional Convention in 1796, Tennessee’s first Representative to the Congress that same year, a U.S. Senator in 1797, and general of the Tennessee militia from 1802 to 1815. During the War of 1812, Jackson became a national war hero for crushing the Creek at Horseshoe Bend and smashing the British at New Orleans. In 1814, a faction of the Creek known as the ‘Red Sticks,’ incited and armed by the British, went on the warpath against the Americans. When Jackson, dying of wounds from a recent duel, heard that the Red Sticks had massacred the men, women, and children of the frontier settlement, Fort Mims, life returned to his body and he sat up in his deathbed, eyes flashing, and bellowed, ‘By the Eternal, these people must be saved!’

His health miraculously restored, Andrew Jackson personally led the militia against the Red Sticks. In retaliation for the massacre at Fort Mims, Jackson burned the Creek villages of Tallussahatchee and Artussee and massacred the men, women, and children (Jackson adopted a young Creek boy whose parents had been killed and raised him as his own son). ‘We shot them like dogs,’ recalled a young Davy Crockett, who regretted the savage revenge and would later become one of Jackson’s staunchest foes. At Horseshoe Bend, Jackson, with the help of the Cherokee, defeated the remnant of the Red Sticks and accepted the surrender of the Red Stick chieftain, Red Eagle (William Weatherford, a ‘half-breed’ son of a white trader and a Creek woman). From his service in the Creek War, Jackson became known as ‘Old Hickory’ among Americans and ‘Jacksa Chula Harjo’ (‘Jackson, Old and Fierce’) among the Creek.

After the War of 1812, Andrew Jackson was appointed as a U.S. general and a U.S. Indian commissioner, and eventually as the military governor of Florida. From 1815 to 1820, Jackson negotiated a series of treaties with the Creek, Cherokee, Chickasaw, and Choctaw which acquired a fifth of Georgia, half of Mississippi, and most of Alabama for the United States.

At the same time, however, the Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Seminole were undergoing a major economic, cultural, and political revolution. Aware that they could not coexist with the whites if they continued in their traditional way of life, these Indian tribes began to acculturate to America, becoming known as the ‘Five Civilised Tribes’ in the process. The Indians abandoned hunting and foraging for agriculture and manufacturing, established schools and churches, built roads and bridges, published newspapers, formed constitutions and bills of rights, dressed in American-style clothing, and intermarried with Americans. At times, the Five Civilised Tribes often seemed more ‘white’ than ‘red’ – so much so that Virginia Senator Henry A. Wise commented that the Cherokee were actually ‘more advanced in civilization’ than most Georgians! For instance, the Cherokee chief John Ross, or White Bird, was the son of a Scottish Tory who had fled to the West to escape persecution in the East and married a Cherokee woman, a veteran of the War of 1812 who had fought beside Jackson at Horseshoe Bend, a framer of the Cherokee constitution, and a landowning and slaveholding planter. In every respect, Ross and Andrew Jackson were equals; indeed, they were once friends.

Earlier, the warlike Indians had posed a threat to the safety of American frontiersman, but the rise of acculturated, ‘civilised’ Indians now posed a threat to the American acquisition of fertile, cotton-growing land. In 1827, the Cherokee adopted a constitution which declared themselves ‘sovereign and independent.’ Georgia, where most of the Cherokee lived, was alarmed by this declaration of independence, and when Andrew Jackson was elected President, nullified the federal treaty with the Cherokee by asserting her sovereignty over the tribe. Georgia was counting on the old Indian fighter’s sympathy and support, and she counted correctly: in Jackson’s first address to the Congress, he accommodated Georgia’s nullification by calling for a policy of removing the Indians from States in the East to territory in the Trans-Mississippi.

Andrew Jackson framed Indian removal as an issue of ‘humanity,’ arguing that if the tribes remained in the East they would be doomed to extinction but if they resettled in the West then their cultures would flourish. As with the ‘Bank War’ (either the Second Bank of the United States or no national bank!) or the ‘Nullification Crisis’ (either submission or disunion!), Jackson had framed a false choice. There was no threat to the Indians’ survival; the only threat was to the Americans’ greed for more land. ‘Those who really control the administration, are governed by the lowest and most sordid object of gain, I do not in the least doubt,’ remarked Vice President John C. Calhoun. ‘Indian treaties and the removal of the Indians with all of their contracts and jobs have doubtless opened a wide field to their cupidity.’ Nevertheless, an Indian removal bill, proposed by a Tennessee Congressman in the House of Representatives and a Tennessee Senator in the Senate, passed in a narrow vote of 102-97 and 28-19, respectively, and was immediately signed into law by Jackson. Congressman Davy Crockett was the sole member of the Tennessee delegation to vote against the bill, an act which cost him his seat in the next election:

I opposed it from the purest motives in the world. Several of my colleagues got around me, and told me how well they loved me, and that I was ruining myself. They said it was a favorite measure of the President, and I ought to go for it. I told them I believed it was a wicked, unjust measure, and that I should go against it, let the cost to myself be what it might. That I was willing to go with General Jackson in everything that I believed was right; but, further than this, I wouldn’t go for him, or any man in the whole creation; I would sooner be honestly and politically d[am]ned, than hypocritically immortalized […] I voted against the Indian bill, and my conscience yet tells me that I gave a good and honest vote, and one that I believe will not make me ashamed in the day of judgment.

The Indian Removal Act authorised the President to demarcate Indian territory on public land west of the Mississippi River and negotiate treaties with the Indian tribes for their resettlement. Resettling Indians were to receive an honest appraisal of their land and fair compensation. Most importantly, in principle, Indian removal was supposed be voluntary. ‘This emigration should be voluntary,’ Andrew Jackson had instructed the Congress, ‘for it would be as cruel as unjust to compel the aborigines to abandon the graves of their fathers, and seek a haven in a distant land.’ In practice, however, Indian removal was fraudulent or forcible, the States of Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi making life so miserable for the Indians that they were left with no choice but to leave. The States abolished the Indians’ tribal American-style governments, banning tribes from enforcing their own laws or even assembling. Indians were subjected to State laws and State taxes but were banned from State polls and State courts. Settlers and speculators squatted on the Indians’ legally protected land, counterfeiting titles and expelling the rightful inhabitants.

Despite these blatant violations of federal treaties and federal law, the Andrew Jackson who was willing to go to war against South Carolina ‘to execute the law’ did nothing to stop the States or save the Indians. As Jackson informed the Choctaw, he was ‘obliged to sustain the States in the exercise of their right.’ Unlike South Carolina, however, which was actually in the right, Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi were in the wrong: the United States had the right to enter into treaties with the Indians. Jackson could and should have enforced the law in those States, but because Jackson believed in Indian removal, however, he enacted Georgia’s nullification into federal law and turned a blind eye to the ensuing crimes.

Due to the severe harassment from the States and the indifference of Andrew Jackson, the Choctaw and the Chickasaw were forced to negotiate treaties of removal. Even then, the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek between the Choctaw and the United States was ratified only after key chiefs were bribed. In the ensuing mass-emigration to the Trans-Mississippi, up to 4,000 Choctaw died from exposure, disease, and starvation. The Creek and the Seminole went to war rather than submit to removal. The Creek were defeated and deported to the west, the captured men in chains followed by the women and children. Up to 10,000 Creek died during the war and subsequent resettlement. The Seminole held out until the United States gave up and decided to let them stay on reservations in the Florida swamps, where their descendants still live to this day.

The Cherokee did not agree to a treaty or go to war, but relied on the law to protect their rights. The Cherokee council of chiefs, led by John Ross, attempted to challenge Georgia’s assertion of State law over the tribe in the Supreme Court, but their suit was dismissed on the grounds that a ‘ward’ had no legal standing against its ‘guardian.’ Counting on Andrew Jackson’s continued support, Georgia escalated its nullification of the federal treaty with the Cherokee, confiscating tribal land and auctioning it off in a statewide lottery. Repeated harassment from Georgia, however, led to the emergence of a pro-removal minority faction among the Cherokee, known as the Treaty Party. The majority of the Cherokee belonged to the anti-removal National Party, which controulled the council of chiefs. When the Cherokee council rejected a treaty negotiated between the Treaty Party and the United States, Georgia responded by arresting and jailing Ross (who was en route to Washington, D.C.) without charges and shutting down the Cherokee newspaper, The Cherokee Phoenix. Frustrated with the Cherokee resistance, the United States simply decided to negotiate with the unrepresentative Treaty Party and at New Echota ratified a treaty without the approval of the Cherokee council.

The Cherokee vehemently protested the fraudulent Treaty of New Echota. Shortly after the negotiations were concluded, John Ross authored a heartfelt memorial to the Senate on behalf of the Cherokee council, begging them not to ratify the treaty:

In truth, our cause is your own. It is the cause of liberty and justice. It is based upon your own principle which we have learned from yourselves; for we have gloried to count your Washington and Jefferson our great teachers. We have practiced their precepts with success and the result is manifest. The wilderness of forest has given place to comfortable dwellings and cultivated fields…We have learned your religion also. We have read your sacred books. Hundreds of our people have embraced their doctrines, practiced the virtue they teach, cherished the hopes they awaken. We speak to the representatives of a Christian country; the friends of justice; the patrons of the oppressed; and our hopes revive, and our prospects brighten, as we indulge the thought. On your sentence our fate is suspended, on your kindness, on your humanity, on your compassion, on your benevolence, we rest our hopes.

The ‘Great Triumvirate’ of John C. Calhoun, Henry Clay, and Daniel Webster, respectively representing the South, the West, and the North, opposed the Treaty of New Echota, but their efforts were to no avail against the Jacksonian majority; the treaty was ratified by a single vote. Although his father was a tough Indian fighter and his family had lost many members to the Cherokee, Calhoun had always been a friend to the Indians. As Secretary of War to President James Monroe, Calhoun had upheld the Jeffersonian policy of acculturation and aid, and he claimed that Andrew Jackson’s policy of Indian removal had ‘fixed a stain on human nature.’ When an old Cherokee chief, Junaluska, who, like John Ross, had been an ally of Jackson’s from the Creek War, heard of the treaty, he raised his head to the sky and wept. ‘If I had known that Jackson would drive us from our homes, I would have killed him that day at the Horse Shoe,’ he lamented.

When the deadline for the removal of the Cherokee arrived, 17,000 Cherokee remained on their land. 7,000 U.S. troops were dispatched to Georgia to enforce the terms of the fraudulent treaty. The troops marched door to door, roughly forcing the Cherokee out of their homes without allowing them to pack any of their property or even gather together all of their family. Property was stolen or auctioned off and families were split. Reverend Evan Jones witnessed the military’s removal of the Cherokee, which he described in the Tennessee Baptist Missionary Magazine:

The Cherokees are nearly all prisoners. They had been dragged from their houses and encamped at the forts and military places, all over the nation. In Georgia especially, multitudes were allowed no time to take anything with them except the clothes they had on…Females who have been habituated to comforts and comparative affluence are driven on foot before the bayonets of brutal men. Their feelings are mortified by vulgar and profane vociferations. It is a painful sight. The property of many has been taken and sold before their eyes for almost nothing – the sellers and the buyers, in many cases, having combined to cheat the poor Indians. These things are done at the instant of arrest and consternation; the soldiers standing by, with their arms in hand, impatient to go on with their work, could give little time to transact business. The poor captive, in a state of distressing agitation, his weeping wife almost frantic with terror, surrounded by a group of crying, terrified children, without a friend to speak a consoling word, is in a poor condition to make a good disposition of his property, and in most cases is stripped of the whole, at one blow. Many of the Cherokees who a few days ago were in comfortable circumstances are now victims of abject poverty…And this is not a description of extreme cases. It is altogether a faint representation of the work which has been perpetrated on the unoffending, unarmed, and unresisting Cherokees…It is the work of war in time of peace.

The Cherokee were marched to military camps where they were to remain until transportation could be arranged for their removal to the Trans-Mississippi. The conditions of the camps were so deadly, however – a drought resulted in starvation and the confined quarters spread disease – that the Cherokee were freed to emigrate themselves. Up to 4,000 Cherokee, a quarter of the entire tribe, died in the camps and on the journey out west. John Ross’ wife died from pneumonia and was buried in one of the many mass graves along the way. This mass-emigration became known among the Cherokee as ‘The Trail Where We Cried,’ or the Trail of Tears.

Long after the Trail of Tears, the Five Civilised Tribes, remembering the treachery and cruelty of ‘Jackson, Old and Fierce,’ and taking to heart the wise words of the Chief John Ross that ‘the perpetrator of a wrong never forgives his victim,’ sought to free themselves from the United States once and for all. Each of the Five Civilised Tribes negotiated a treaty of alliance with the Confederate States of America, in exchange for the promise that they would have a State of their own rather than reservations. At a convention in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, the Cherokee declared their independence from the United States and their ‘common cause’ with the Confederacy. ‘Whatever causes the Cherokee people may have had in the past, to complain of some of the Southern States, they cannot but feel that their interests and their destiny are inseparably connected with those of the South,’ explained the Cherokee. ‘Menaced by a great danger, they exercise the inalienable right of self-defense, and declare themselves a free people, independent of the Northern States of America, and at war with them by their own act.’ At the bottom of the Cherokee Declaration of Independence was the signature of John Ross.

The Verdict

Andrew Jackson’s legacy is complicated, though on the whole negative. True, he had scaled back the size of the federal government and opened up the government to the plain folk, but at the cost of turning the presidency into an American Caesar and creating a vulgar, partisan form of politics. Today’s imperial presidency and dysfunctional party system is distinctly Jacksonian.

Andrew Jackson opposed nullification and secession, rendering the States powerless to limit the usurpations of the federal government and denying them the most basic freedom of all – the freedom to leave. By emphasising the Union’s form over its meaning, Jackson insured that the Union would be preserved physically but destroyed philosophically. Today, on economic issues such as healthcare or social issues such as same-sex marriage, the States have no recognised recourse against an increasingly intrusive federal government. Those who celebrate when controversial issues go their way should be warned that unchecked, uncontroulled, consolidated power can just as easily go against them as for them.

Andrew Jackson betrayed and abused the Indians, placing the economic interests of Americans over the Indians’ treaty rights, which were the supreme law of the land according to the Constitution. The United States’ endless crusades to ‘spread democracy’ to foreign countries (yesterday, it was Afghanistan and Iraq; today, it is Syria and Ukraine), even if it means destabilising entire societies and destroying countless lives, closely resembles Jackson’s self-interested, self-righteous Indian removal, which also professed humanitarian motives while displaying an utter indifference to human costs.

Yet Andrew Jackson should not be removed from the twenty-dollar bill (neither, for that matter, should Alexander Hamilton, who for better or for worse is the father of America’s current financial and political system, be removed from the ten-dollar bill).

For one, there is an overwhelming degree of Yankee hypocrisy and anti-Southern discrimination in singling out Jackson for purging. True, Jackson was treacherous and tyrannical to the Indians. Yet so was the sainted President Abraham Lincoln, who ordered the largest mass-execution of Indians in American history (Sioux braves hanged for resisting corrupt federal agents and raiding American settlers). So was President Ulysses S. Grant, the vaunted saviour of the Union, who presided over the near-genocide of the Plains Tribes – a war with the motto ‘the only good Indian is a dead Indian.’ Nevertheless, there is not and there never will be any outcry to remove Lincoln and Grant from the currency; such ugly truths would shatter the Yankee fable of American history.

The campaign to remove Andrew Jackson from the currency has the added force of proposing to replace him with a woman. The top three candidates appear to be Harriet Tubman (a self-emancipated slave, ‘conductor’ of the Underground Railroad, and conspirator with the terrorist John Brown), Eleanor Roosevelt (the wife of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, human-rights activist, and a fountain of quotations for valedictorian speeches), and Wilma P. Mankiller (the first female Cherokee chief). Sadly, Abigail Adams (the companion and conscience of the ‘tongue’ of the American Revolution, John Adams), Mercy Otis Warren (a Revolutionary and Anti-Federalist poetess, playwright, pamphleteer, and author), and Dolley Madison (the ‘queenly’ lady who defined the role of the First Lady) have been slighted yet again. Instead of removing and replacing figures from the currency, however, simply eliminating duplication would create new openings for women. Restore the circulation of the two-dollar bill with Thomas Jefferson and put a woman on the nickel (my vote is for his friend, Abigail). George Washington and Abraham Lincoln already have the one- and five-dollar bill; remove them from the quarter and the penny and replace them with women. This situation can and should be resolved with compromise, not conflict.

The fundamental question, however, is how the present should treat the past. The answer is that history is not a proposition up for a vote: it is a heritage – roots which cannot be pulled up without toppling the tree. Purging history and insulting long-dead historical figures is a petulant and cowardly indulgence (for a good laugh, imagine one of these shrill, stupid, and spineless college-campus communists explaining to Andrew Jackson why he has become politically incorrect – they would learn a whole new meaning of the term ‘trigger warning’). The fact of the matter is that Jackson is simply too important and influential of a historical figure to be purged. Like him or not, Jackson defined a time, a place, and a people in a way which few Americans have ever done. A far more constructive pursuit would be to reflect on how Jackson influences America today and to preserve what is good (and there is some good) and to remove what is bad (and there is plenty bad) – in other words, to purge Jackson’s influence rather than his image.

jackson really has a vivid imagination. ‘breaks the unity’? if one part is being un-unified in its excercise of power over another…that sounds far from unified. the unity only tenuously existed anyway…and under certain cimcumstances and the desires of the parties (free and independent States) seeking a conditional-unity. when numerous things leave a so-called unity, you then have other unities. the Declaration proclaimed sovereign and independent states, including the one jackson came from. he never seems to invoke that though.