Criss-crossing the South, from Virginia and Maryland to Texas, and from Missouri and Tennessee to South Carolina and Florida, there are thirteen museums dedicated to the myriad oddities of life . . . Robert Ripley’s “Odditoriums.” Almost a century ago, as a reporter for the New York Globe, Ripley created what would soon become the world-famous media feature, “Believe It Or Not,” in which unusual items of all types, including little-known footnotes to history, were introduced to the public. Then, in 1950, the first permanent collection of Ripley’s oddities was opened in Florida at St. Augustine’s 19th Century Warden Castle, the winter home of William G. Warden, a business partner of John D. Rockefeller and Florida land developer, Henry Flagler. As the name “Believe It Or Not” implies, however, people have always been given the opportunity to judge whether or not they wished to believe what Ripley portrayed as being factual. More importantly though, and perhaps without realizing it, the concept of Ripley’s presentations actually went to the very heart of one of the most vital aspects of human existence . . . that which we believe to be true or false.

One the most basic of such beliefs would, of course, involve religious faith. Since the beginning of recorded history, humans have believed in things that, in one way or another, attempted to explain the inexplicable mysteries of life, as well as provide some measure of guidance to their daily existence. At first, such things were undoubtedly visible heavenly or earthly objects to which certain magical powers were ascribed. In time, as civilization progressed, the concept of revering such objects evolved into the worship of unseen deities which were then transformed into tangible idols that finally led to the creation of highly developed religious practices. Then, about four millennia ago, a group of Middle-Eastern people developed the unique and revolutionary concept of a single, almighty deity who had created the entire universe and everything it contained, including mankind itself. Since none of the sciences with which we are we are familiar today . . . archaeology, paleontology, anthropology or geology, let alone the basic process of evolution, were known to these ancient people, the new concept had to be explained in terms that could be easily grasped by the people of that age. In addition to the stories that were developed to explain the idea of God and creation, an entire new code of morals and ethics was also woven into these tales, and then great events that had been recorded by earlier civilizations, such as mighty floods and other disasters that had greatly affected the known world, were added as a means of further explanation.

About a thousand years later, these initial explanatory and historical tales would finally be codified into what is known today as the books of the Old Testament, and ultimately the religion of Judaism. Then, after a further thousand years had passed, these same writings and the basic beliefs which grew from them would, in turn, give birth to the second great monotheistic religion, Christianity. Six centuries later another Middle-Eastern prophet and teacher, Mohammed, would transform the original religion still further with the creation of the third monotheistic faith, Islam. While following different paths, each of these three faiths, as well as the many other forms of religious worship that were developed by people throughout the world, are all based on the concept of what an individual or group wishes to believe . . . or chooses to reject. Sadly, however, history has shown that many were not content with merely accepting their chosen faith, but felt they must also force their beliefs on others, thus leading to holy wars, inquisitions, sectarian strife and persecutions which ultimately led to the extermination of millions and the destruction of that in which others devoutly believed.

What we hold to be true or false also extends into other basic fields of human existence, such as the economic, political and social systems under which we live, as well as the recorded history of such matters. As with religion, while differences in one’s approach to the political or social systems in which we believe can merely serve as a benign subject of individual choice and philosophical discourse, such differences can also lead to unreasoning fear or hatred, societal persecution or even actual conflict, with an excellent case in point being the American Civil War. In order to be politically correct today, one is forced to accept the premise that the North went to war to free the Southern slaves and that the South treasonously fought to defend its “peculiar institution,” as well as firing on Fort Sumter as an overt act of Southern aggression. All Southern arguments that present any alternate facts detailing the actual economic, political and social causes of the War are, of course, ignored. Likewise, anything citing the fact that there is no specific clause in either America’s original Articles of Confederation or the subsequent Constitution which forbids the withdrawal of a state from the contract into which it voluntarily entered is also summarily dismissed as Southern propaganda to justify secession. The truth is that had such a restriction been inserted, it is highly doubtful if either document would have been ratified.

Today, both slavery and racial intolerance are presented, and generally accepted, as being unique to white Southerners. Even a cursory examination of history, however, would reveal that slavery actually began in the North, particularly in New England and New York in the 17th Century, and was ultimately exported to the South. As an example, a recent film based on the 1853 narrative of Solomon Northup’s ordeal, “Twelve Years a Slave,” fails to mention the fact that Northup’s father was a slave in Rhode Island . . . not in the South. Furthermore, just prior to the time Northup’s father was given his freedom in New York, that state contained over 13,000 slaves, the second highest slave population in America, and that more than 35 per cent of all immigrants entering New York City did so as slaves. New York was also the scene of some the earliest slave uprisings, and in 1741 slaves attempted to burn down all of Manhattan. That revolt was brutally put down, with over a hundred slaves being hanged, burned alive or exiled.

It is also a fact that slavery and the slave trade in the North did not end until the early part of the 19th Century, and as late as 1865 in New Jersey. The same holds true in relation to racial discrimination and prejudice, and while the de jure “Jim Crow” segregation laws in the South are portrayed as being the sole representative of racial repression in America, we seldom, if ever, hear now of similar de facto segregation in the North. On that note, perhaps one of the greatest miscarriages of history is the portrayal of Abraham Lincoln as the “great emancipator” and the fatherly benefactor of African-Americans, when in truth history actually shows that Lincoln was not in favor of outright abolition, that he advocated a policy of slave colonization outside America, and on numerous occasions publicly stated his opinion that whites were superior to blacks and since the two races were incompatible, they would be unable to live together in harmony . . . feelings which were shared by many, if not most, Northerners both in Lincoln’s day and well into the 20th Century. In regard to this, while the Ku Klux Klan did originate in the South during the post-war Reconstruction era, by the mid-1920s the KKK had become a national anti-Black, anti-Semitic and anti-Catholic organization with as many as six million members, and 250,000 of them in Indiana alone. Other areas in the North also had large KKK groups, such as Detroit Michigan’s 40,000 members, with smaller chapters reaching all across the North, from Oregon and Washington State to New York and New England.

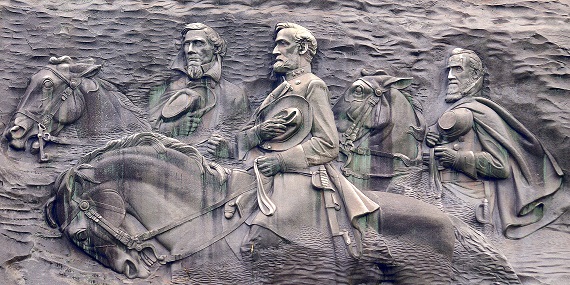

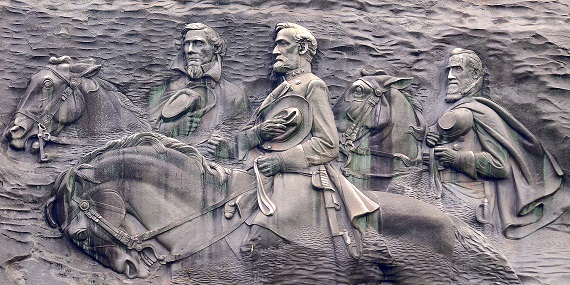

Prejudice, however, presents a nasty saber that can cut both ways. Far too many people all across America today, both black and white, now believe, or are led to believe, that most ill will towards African-Americans is based on the perceived feelings of racism in the South that date back to the 19th Century and the cause that was lost in 1865. Because of this, the same voices that cry out against this so-called Southern racism also believe they can shout ethnic epithets with impunity at not only the people of the South, but the history and traditions in which Southerners firmly believe. While these cries also include demands to permanently furl the banners of the Confederacy, many would like to carry their feelings against what they see as Southern prejudice still further. Like the Islamic Taliban in Afghanistan who, during 2001, blew apart the 6th Century Bamiyan Buddha statues, as well as the more recent acts of wanton destruction carried out by the so-called Islamic State against Assyrian, Roman and Christian antiquities, merely because each represents something in which the Islamic fanatics do not believe, there are those in America who now call for the total destruction or removal of Confederate statues and monuments, including even the historic carvings of President Davis and Generals Lee and Jackson on Stone Mountain in Georgia.

That in which one sincerely believes, even if others feel such faith might be misguided or misplaced, should, of course, be respected at all times. Likewise, those who hold opposing points of view should also be allowed to do so without being vehemently attacked. To rationally discuss, or even strongly debate, matters of mutual disagreement is one thing, but the strident accusations that are being hurled across racial and religious barricades today, and the acts of violence which are being committed in the name of civil rights and social justice are, like those of the Taliban and ISIS, merely nothing more than crimes against history and humanity. It is time, therefore, for those with opposing viewpoints, while firmly holding onto their our own beliefs, to at the same time be willing to honestly attempt to gain a meaningful understanding of the things in which others believe . . . or do not believe.