The Pledge of Allegiance is neither a sacred American tradition nor a patriotic duty, but a relatively recent piece of propaganda penned specifically to eradicate the memory of America’s revolutionary heritage and to indoctrinate the American people into believing lies about their history. If General George Washington ever heard the Pledge, he would not have put his hand on his heart, but rather drawn his sword.

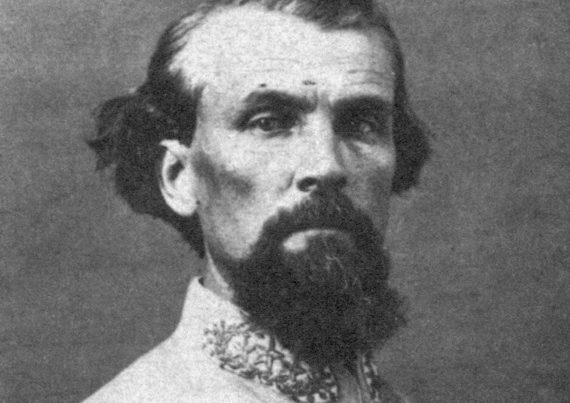

The author of the Pledge was Francis Bellamy, a self-described “Christian Socialist” from Boston. Bellamy’s cousin and collaborator, Edward Bellamy, wrote a novel called “Looking Backward,” in which a man time-travels from 1888 to the future to discover that America has become a socialist utopia: equality is enforced and the entire economy is controlled by the government. Bellamy served as a Baptist preacher for awhile, but was stripped of the cloth for teaching the heresy that “Jesus was a socialist.”

In 1892, Bellamy wrote his Pledge. Recognizing that public schools controlled the impressionable young minds of future generations, Bellamy campaigned with the National Education Association to introduce his message of blind obedience to an omnipotent central government to the classroom.

By 1942, the Pledge was formally adopted by the U.S. Congress, though the Nazi salute which Bellamy recommended accompany its recitation was replaced it with the hand over the heart – less offensive, perhaps, but no less worshipful of a gesture.

Bellamy explained that his motive in composing the Pledge of Allegiance was to indoctrinate the American people into accepting the centralized nation-state into which Lincoln and the North had brutally and bloodily hammered the Founding Fathers’ decentralized republic of sovereign states:

The true reason for allegiance to the Flag is the ‘republic for which it stands.’ And what does that vast thing, the Republic mean? It is the concise political word for the Nation – the One Nation which the Civil War was fought to prove. To make that One Nation idea clear, we must specify that it is indivisible, as Webster and Lincoln used to repeat in their great speeches.

Webster, the acknowledged inspiration of the Pledge of Allegiance, stood in stark opposition to early American patriots like Jefferson, Henry, Lee, Randolph, Taylor, and Calhoun, some of whom were heroes of the Revolutionary War. His theory of “one nation, indivisible” was concocted around the late 1820s as a pretext for the North’s neo-mercantilist/proto-fascist agenda of taxing the South to protect Northern industries from competition while spending the proceeds in the North. Before the dawn of this fabricated ideology, however, the divisibility of the Union was freely and fairly acknowledged on both sides. For example, facing the prospect of the North seceding in protest of the expansion of Southern territory, President Jefferson remarked, “If any state in the Union will declare that it prefers separation to a continuance in the Union, I have no hesitation in saying, ‘Let us separate.’” According to Jefferson, “It is the elder and younger son differing. God bless them both, and keep them in the Union, if it be for their good, but separate them, if it be better.”

By the end of his life, Jefferson despaired at the tremendous growth of federal power (Bellamy was giddy at the prospect), and concluded that Southern secession may ultimately be liberty’s only hope:

I see with the deepest affliction the rapid strides with which the federal branch of our government is advancing toward the usurpation of all rights reserved to the States, and the consolidation in itself of all powers, foreign and domestic; and that by constructions which, if legitimate, leave no limits to their power…We must separate from our companions only when the sole alternatives left are the dissolution of our Union with them, or submission to a government without limitation of powers.

Around the same time, President John Quincy Adams, although an early acolyte of Webster, realized that the interests of the North and South were diverging, and that secession – if not technically rightful under Webster’s tortuous constitutional constructions – was not only natural, but also necessary:

Thus stands the right. But the indissoluble link of union between the people of the several States of this confederated nation is, after all, not in the right, but in the heart. If the day should ever come (may Heaven avert it) when the affections of the people of these States shall be alienated from each other; when the fraternal spirit shall give way to cold indifference, or collision of interest shall fester into hatred, the bands of political association will not long hold together parties no longer attracted by the magnetism of conciliated interests and kindly sympathies; and far better will it be for the people of the disunited States to part in friendship from each other, than to be held together by constraint.

Although as different as two men can be, the magnanimity of Jefferson and Adams on the divisibility of the Union stands in stark contrast to the malevolence of Lincoln and his malignant war party. Alexander de Tocqueville, a French intellectual who studied Antebellum American society, concluded, “If the Union were to enforce by arms the allegiance of the federated States, it would be in a position very analogous to England at the time of the War of Independence.” De Tocqueville continued:

The Union was formed by the voluntary agreement of the States; and these, in uniting together, have not forfeited their nationality, nor have they been reduced to the condition of one and the same people. If one of the States chooses to withdraw from the compact, it would be difficult to disprove its right of doing so, and the federal government would have no means of maintaining its claims directly either by force or right.

Despite the triumph of force of arms over consent of the governed in the War of Southern Independence, Bellamy feared that the war was not yet won in the minds of Americans. America’s strong culture of individualism and heritage of republicanism – deeply rooted in the rebellious South – still posed a threat to the new world order which Bellamy envisioned. The Pledge of Allegiance was his insidious attempt to complete the Northern subjugation of the South by replacing the memory of the Founding Fathers’ love of liberty with loyalty to the government – now an “indivisible nation” forged in blood and iron. Yet, according to the Declaration of Independence, governments existed solely to protect the liberty of the people, and could and should be dissolved if they ever betrayed this duty. While most Founders were bitterly opposed to the idea of a “nation” over a republic, believing that the vertical as well as horizontal separation of power was an important part of their system of checks and balances, an “indivisible” government – a totalitarian concept which was never even broached in their time – would have been an utter outrage. After all, the American Colonies had individually seceded from the British Empire as “free and independent States,” and were individually recognized as “free, sovereign, and independent” in their peace with the King. “Each State,” concurred the Articles of Confederation, “retains its sovereignty, freedom, and independence, and every power, jurisdiction, and right which is not by this confederation expressly delegated to the United States, in Congress assembled.” The sovereignty of the states and divisibility of the Union was well-recognized and respected prior to the Constitution.

As a condition of ratifying the Constitution, a majority of the states from the North and South explicitly stipulated that they retained their sovereignty. As John Randolph of Roanoke colorfully illustrated years later, “Asking one of the States to surrender part of her sovereignty is like asking a lady to surrender part of her chastity.” Virginia’s assertion of state sovereignty was the most comprehensive: “We the Delegates of Virginia…do in the name and in behalf of the People of Virginia declare and make known that the powers granted under the Constitution being derived from the People of the United States may be resumed by them whensoever the same shall be perverted to their injury or oppression.” In other words, if the federal government ever abused the powers with which it had been entrusted by the states, then the states were free to reclaim those powers for themselves. In a long list of proposed amendments to the Constitution, Virginia’s foremost was what would ultimately be adapted into the Tenth Amendment – what Jefferson considered the “foundation” of the Constitution: “First, that each State in the Union shall respectively retain every power, jurisdiction and right which is not by this Constitution delegated to the Congress of the United States or to the departments of the Federal Government.” Indeed, the Ninth and Tenth Amendments were adopted to reassure the states that they retained their sovereignty in the Union, affirming that the absence of any enumerated rights should not be misconstrued as a denial of those rights, and that the states reserved unto themselves any rights which they did not delegate to the federal government. As James Madison claimed in the Federalist Papers, “The new Constitution will, if established, be a federal, and not a national constitution.” Elsewhere, Madison referred to the “sovereign power” of the “distinct and independent States.” The ratification of the Constitution depended upon the preservation of the sovereignty of the states and divisibility of the Union.

When the epic political, economic and cultural conflict between the North and the South culminated in secession, the Confederacy avowed that it was faithfully following in the footsteps of the Founding Fathers:

The declared purpose of the compact of Union from which we have withdrawn was to ‘establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessing of liberty to ourselves and our posterity.’ When, in the judgment of the sovereign States now composing this Confederacy, it had been perverted from the purposes for which it was ordained and had ceased to answer the ends for which it was established, a peaceful appeal to the ballot box declared that so far as they were concerned, the government created by that compact should cease to exist. In this they merely asserted a right which the Declaration of Independence of 1776 had defined to be inalienable; of the time and occasion for its exercise, they as sovereigns were the final judges, each for itself.

– President Jefferson Davis, First Inaugural Address, 2/18/61

Strange, indeed, must it seem to the impartial observer, but it is nonetheless true that all these carefully worded clauses proved unavailing to prevent the rise and growth in the Northern States of a political school which has persistently claimed that the government thus formed was not a compact between States, but was in effect a national government, set up above and over the States. An organization created by the States to secure the blessings of liberty and independence against foreign aggression has been gradually perverted into a machine for their control in their domestic affairs. The creature has been exalted above its creators; the principals have been made subordinate to the agent appointed by themselves.

– President Davis, Message to Congress (Ratification of the Constitution), 4/29/61

Bellamy, proving that history is indeed written by the victors over the vanquished, penned his Pledge with the hope that these revolutionary truths – dire threats to his vision of a central government reigning supreme over a united nation – would be forgotten forever. Might merely settles questions of force, not of right, and while a lost cause can rise again, a lost memory may never be redeemed.

One Comment