The Roman historian Titus Livius once called Rome “the greatest nation in the world.” He wrote those words in a time of moral and political decline, and Livy was hoping by outlining the greatness of the once proud republic, the Roman people would arrest the decline and embrace the principles that had made Rome great. Livy argued that without understanding their history, the Roman people would neither be able to “endure our vices nor face the remedies needed to cure them.” But Livy failed to recognize the catastrophic effect empire and expansion had on the Roman spirit. For example, by expanding north and attempting to assimilate the Germanic peoples and the Celts into Roman culture, Rome sealed its own demise. The Germans and Celts never fully embraced Rome, and those who did retained some element of their own political and cultural heritage. Romans were outnumbered by Germanic peoples in their own army, and the disintegration of the Empire seemed inevitable as the fringes of the Empire came under constant assault from groups unwilling to assimilate. There was never a Roman “nation” outside of Rome. The men, money, and material needed to build and then hold the Empire were wasted, while the vices and decadence of the ruling class in Rome wrecked the republic. The human cost of the Roman Empire was incalculable.

On a human scale, decentralization made more sense for those under the yoke of Roman domination. Constant wars against foreign peoples, heavy taxes, and alien government was for many an unfair trade for Roman laws, “stability, and “protection.” Certainly, many people in Europe prospered under Roman control and the “Pax Romana,” but the internal tensions and cultural sacrifices were too large of a burden for the Empire to contain. It was only a matter of time before people realized that they were better off under local control.

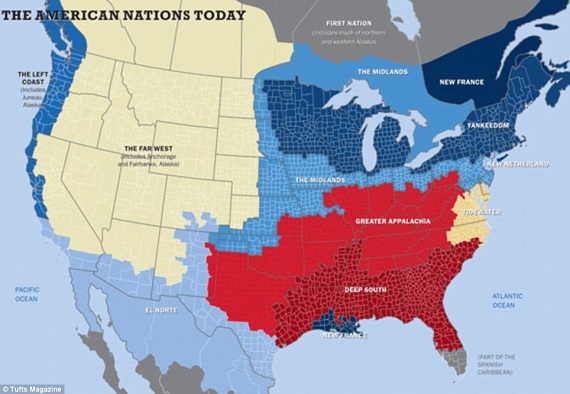

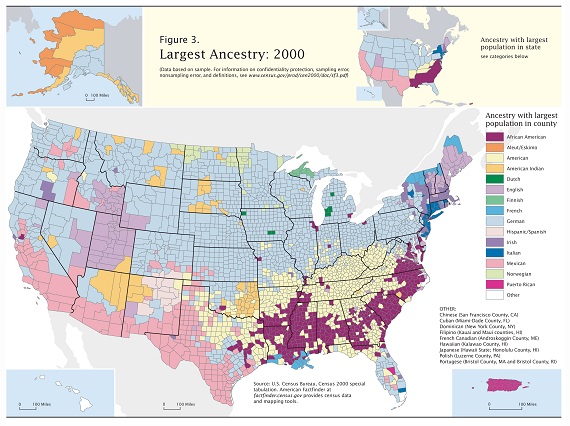

Studying the rise and decline of empires has long been instructive for Americans, and for decades, historians, philosophers, economists, diplomats, statesmen, and others have warned against the American Empire. Yet, rarely did those who railed against expansion focus on the human cost of the empire and the political and social marginalization that naturally follows an impersonal government. Like Rome, a demographic map from the 2000 United States Census (see below) emphasizes that an American “nation” does not exist, and it is only through the power and propaganda of the “United State” that decentralization has failed to materialize. Obviously, sections still exist and the human cost of the American empire within the 50 States appears to be significant on several levels.

First, the United States should be at minimum broken into the several cultural sections clearly defined by the map. The Northeast, or Deep North, has a cultural identity vastly different than the South. The West, most importantly the Southwest, has a cultural mix inconsistent with the rest of the United States. Richard Henry Lee, among others, recognized this in 1787 when he wrote in the Letters From the Federal Farmer to the Republican that, “free elective government cannot be extended over large territories [and] one government and general legislation alone, never can extend equal benefits to all parts of the United States: Different laws, customs, and opinions exist in the different states, which by a uniform system of laws would be unreasonably invaded. The United States contain about a million of square miles, and in half a century will, probably, contain ten millions of people; and from the center to the extremes is about 800 miles.” The United States now covers almost 4 million square miles and around three-hundred million people. If Lee was correct in 1787, and he was, then he would surely be correct today.

Second, one of the longstanding critiques of large governments is the impersonal and ultimately tyrannical nature of powerful centralized authority. The French philosopher Baron de Montesquieu in his The Spirit of Laws opined that a large republic was unmanageable unless consolidated in a federal or confederated system. British philosopher David Hume, in Idea of a Perfect Commonwealth, argued that decentralization was the only way to ensure the greatest level of liberty. Of course, the founding generation was well aware of the arguments for decentralization set forth by the classical Greeks and those of both Enlightenment philosophers. Lee, in the same Letters From the Federal Farmer, followed a similar line of thinking we he suggested that the people of the States should have a means of defense against the central government. He said, “I believe the position is undeniable, that the federal government will be principally in the hands of the natural aristocracy, and the state governments principally in the hands of the democracy, the representatives in the body of the people. These representatives in Great-Britain hold the purse, and have a negative upon all laws. We must yield to circumstances, and depart something from this plan, and strike out a new medium, so as to give efficacy to the whole system, supply the wants of union, and leave the several states, or the people assembled in the state legislatures, the means of defense.” In other words, Lee was arguing for the States to have a limited negative power over the central government—a “defense”—to protect the cultural, economic, and social interests of their separate communities, an action called nullification or state interposition today. It was the most democratic thing to do.

Third, most opponents of decentralization, secession, or nullification argue that minorities would be unjustly impacted should States begin to reassert their sovereignty through nullification or secession. This is dead wrong. As John C. Calhoun emphasized, nullification was used to protect minority interests from the tyranny of the majority. Secession followed the same pattern. Regardless, American minorities today believe that they have the greatest power in the central government, and that State and local communities, particularly in the South, would infringe on minority rights. But this position belies reality.

Data from two Southern States, Mississippi and Alabama, clearly indicates that black Americans are better represented at the State level than in the central government. There are currently two black members of the United States Senate, and blacks only comprise approximately nine percent of the United States House of Representatives. In total, blacks account for around thirteen percent of the American population, so they are vastly underrepresented in Washington D.C. Conversely, blacks hold thirty percent of the seats in the lower house of the Mississippi legislature and twenty-five percent of the seats in the upper house. In Alabama, blacks comprise twenty-three percent of both the lower and upper house. Blacks account for thirty-seven percent of the total population in Mississippi and twenty-six percent of the total population in Alabama, making representation in both States more equitable than in Washington D.C. If counties could have a negative veto over State law, minorities would have an even greater political and social impact in their own community. This would comport to Hume’s ideal republic and to the nature of minority Cantons in the Swiss federation.

As Kirkpatrick Sale and Don Livingston have repeatedly emphasized, decentralization has once again entered the public discourse. Unfortunately, it is often portrayed as simply reactionary when it is, in fact, the American tradition. Selling it in an era of economic and social collapse has become easier, but the rhetorical roadblocks of racism and treason still exist. See any social media comments after someone simply presents the option. Thus, decentralization still is a hard sell, but it can be done by emphasizing that the prospect of more local control offers greater political and economic liberty and stronger protection for cultural, religious, and racial minorities. It is the future of America and the future of a free world.