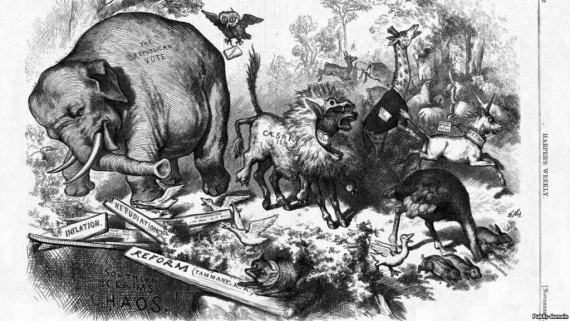

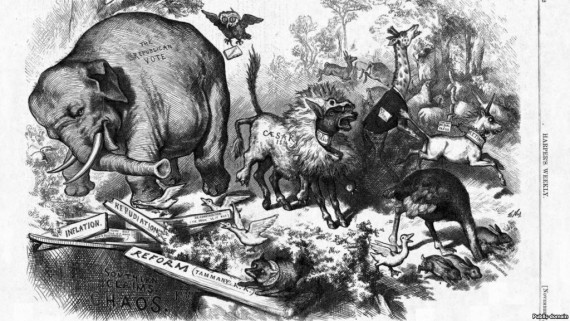

The origin of the elephant as a symbol of the Republican Party occurred in 1874 after a political cartoon by Thomas Nast appeared in the popular New York newspaper, “Harper’s Weekly.” It was during the congressional elections of that year when Nast, a renowned Republican satirist, drew a picture of the Democratic donkey dressed in a lion’s skin frightening away all the animals except one, an elephant that Nast dubbed “the Republican vote.” The cartoon was an instant hit with Republicans who quickly adopted the mighty animal as the party’s emblem. The Democratic donkey was also popularized by Nast in his cartoons, but its genesis dated back to the presidential elections of 1828 in which the National Republican Party labeled Democrat Andrew Jackson as a jackass. “Old Hickory,” however, turned the slur against his opponents by adopting the the image of a feisty, stubborn donkey for his own campaign posters, and went on to swamp President John Quincy Adams by winning over 56 per cent of the popular vote. Both party symbols have continued to the present day, with the ebullient equine still braying its opposition to the ponderous pachyderm.

What, however, is a “democrat” or a “republican” literally? Both the concepts of democracy and republicanism date back to the Sixth Century BCE in ancient Greece and Rome. In Greece, the word “demokratia” meant the rule of the people, and the earliest democracy was the creation of the Athenian statesman and political thinker, Cleisthenes, who advocated a type of pure democracy in which every Athenian citizen had a direct voice in all political matters and appointments. Athenian citizenship, however, was not extended to women, males under the age of twenty, non-landowners or slaves. The Roman Republic, or “res publica,” affair of the people, in Latin, saw its birth in ancient Rome during the same period when Lucius Tarquinius Collatinus and Lucius Junius Brutus led the overthrow of the Roman kings and established the form of representative government known as a republic in which the citizens of Rome, while retaining their popular (i.e., individual) sovereignty, elected men to represent them in the Roman Senate. In Rome, the exclusions concerning the term “citizen” were applied in the same manner as they were in Greece . . . and as they would again be applied over two millennia later with the founding of the American Republic.

While the actual concepts of democracy, republicanism and citizenship have taken on quite different connotations over the intervening centuries, both of today’s major political parties can trace some portion of their tangled roots back to all of America’s earlier parties, the Federalists, the Democratic-Republicans, the National Republicans, the Whigs and even the American Party, better known as the “Know-Nothings.” Abraham Lincoln’s Republican Party, however, was primarily an extension of Henry Clay’s moribund Whig Party whose so-called “American System” advocated a strong central government, federally financed national projects and a highly protective tariff on foreign goods, as well as being opposed to the extension of slavery into any of the territories, and with many, but not all, of its members being outright abolitionists. The rapid decline of the Whigs began with the split created within the party by the Compromise of 1850 relative to the admission of free and slave states into the Union, and was then compounded by the deaths of their two major leaders, Henry Clay and Daniel Webster, in 1852. The party’s ultimate downfall was in November of that year with its landslide defeat in the presidential elections in which the Whig candidate, General Winfield Scott, the hero of the War of 1812 and the Mexican War, lost overwhelmingly to Democrat Franklin Pierce, with Scott winning just 14 per cent of the popular vote and only forty-two of the 296 electoral votes. Most Whigs, including Abraham Lincoln, felt that any sort of meaningful reform was hopeless and began to leave the party in droves . . . with many in the South moving to the short-lived Whig-American Party, and those in the North opting for the newly-formed Republican Party.

While most historians cite the Republican Party as having been born on February 28, 1854, at a Congregational Church meeting in the village of Ripon, Wisconsin, the party was actually conceived at a hotel in New York City two years earlier. In 1852, a leading Whig politician and Ripon attorney, Alvan E. Bovay, traveled to New York for a meeting at Lovejoy’s Hotel with Horace Greeley, the editor of one of that city’s leading newspapers, “The New York Tribune,” to discuss the formation of a new political entity. Bovay suggested naming it the Republican Party to try attracting former members of both the defunct Democratic-Republican and National Republican Parties. By a twist of fate, Lovejoy’s was one of the twelve New York hotels that Confederate agents attempted to burn down in November 1864. Two years after Bovay’s meeting with Greeley, the new party was formed at that church in Ripon, and by the summer of 1854 Republican organizations had also been established in Michigan, Vermont, Ohio, Indiana, New York and Massachusetts. The following year the party added eight more state committees and had elected eleven U. S. senators. In 1856, the Republicans were a national party and ready for that year’s presidential elections.

The Republicans held their initial presidential nominating convention in Philadelphia in June of 1856, and selected the former explorer, Mexican War major and California senator, John C. Frémont, known as “the Pathfinder,” as their presidential candidate. Frémont’s Democratic opponent was James Buchanan who won the election with a little over 45 per cent of the popular vote to Frémont’s 33 per cent. The spoiler in the race was former President Millard Fillmore who took over 21 per cent cent of ballots as the candidate of the recently formed Whig-American Party. The electoral vote, however, was more decisive, with Buchanan gaining 174 votes against Frémont’s 114 and Fillmore’s eight in Maryland. Four year later, however, it would be the Republican candidate, Abraham Lincoln, who would become the minority winner with just under 40 per cent of the popular vote against the Democrats who were split three ways, with the regular Democratic Party standard bearer, Senator Stephen A. Douglas, receiving 29.5 per cent of the votes; the Southern Democratic candidate, Vice-President and soon-to-be Confederate general and the C. S. A.’s secretary of war, John C. Breckenridge, with 18 per cent; and the Constitutional Union nominee, former Speaker of the House John Bell, who took the remaining 12.6 per cent. Lincoln, however, won the greatest number of votes in the Electoral College, 180 out of 303. Of course, had the Democrats been united behind a single candidate, America’s and the South’s histories might have been far different, with the tragic events that followed Lincoln’s election perhaps being avoided.

With the Southern states absent from the 1864 elections, the combination of Sherman’s victories in Georgia and the power wielded by a Republican administration backed by the Union Army allowed Lincoln to roll over his Democratic opponent, the former commander of the Union forces, General George B. McClellan, with 90 per cent of the electoral votes. By the next election in 1868, the defeated South was under the military occupation of the Reconstruction period, with large numbers of white voters disfranchised and the balloting strictly controlled by both the Union Army and the auxiliaries of the Republican Party, the Union Leagues, whose job it was to bring the newly freed and enfranchised black voters to the polls. All of this insured that the Republican candidate for president, General Ulysses S. Grant, would prevail over Democrat Horatio Seymour, the former governor of New York, winning 214 of the 294 electoral votes. Four years later, and under virtually the same conditions, while President Grant did stop the bid of former Republican Horace Greeley, the editor of the “New York Tribune,” the Democrats finally managed to win back five Southern states, Georgia, Kentucky, Missouri, Tennessee and Texas.

Over the following twelve years, the Democrats continued to gain back power in the South and in 1884, after a quarter of a century of Republican rule, the party finally won back the White House with Grover Cleveland’s razor-thin victory over Republican James G. Blaine . . . Cleveland getting 48.9 per cent of the popular vote to Blaine’s 48.2 per cent, as well as winning a bare majority of the electoral votes, 219 to 182. Certainly, the new “Solid South” had contributed much to Cleveland’s victory, and the region was to remain a strong Democratic bastion until well into the next century regardless of which party occupied the White House. The Democratic Party’s hold on the South was also aided by a number of state-wide political machines that rose to power in the early Twentieth Century, such as those of Georgia Governor Eugene Talmadge; Governor Huey Long in Louisiana; Senator and former Governor Theodore G. Bilbo of Mississippi; and Senator and former Governor Harry F. Byrd’s “Organization” in Virginia. There were also several city-based Democratic Party machines throughout the South that wielded great state-wide influence, like “Chief” John B. Kennedy’s “Cracker Party” in Augusta, Georgia; Thomas J. Pendergast’s group in Kansas City, Missouri, that brought Harry S. Truman to the U. S. Senate, and ultimately the White House; and “Boss” Edward H. Crump’s thirty-year reign in Memphis, Tennessee. The only crack in the “Solid South” came in 1928 when several states defected to the Republicans over the Catholicism of Democrat Alfred E. Smith of New York, but they all returned to the fold four years later with the landslide victory of Franklin D. Roosevelt. While some of the Southern leaders, such as Governors Long and Talmadge, and Senator Byrd ultimately broke with Roosevelt over the extremely left-leaning direction being taken by the New Deal, Postmaster James A, Farley, FDR’s campaign manager and chairman of the Democratic National Committee, managed to maintain the party’s power in the South through the dispensing of political patronage vis the U. S. Postal Service and such New Deal make-work organizations as the Work Projects Administration and the Civilian Conservation Corps.

Over the years, however, the political principals of most Southern Democrats remained basically conservative, holding true to the dictates of Thomas Jefferson, As pointed out, FDR’s New Deal produced a radical transformation in overall Democratic ideology and an ever-widening expansion of the federal government at the expense of state’s rights. While this sudden shift to the left in the mid-1930s caused some of the South’s leaders to turn away from the New Deal, it took more than a decade for the effects of this new direction to filter into the thinking of the majority of Southern Democrats. The 1948 presidential elections produced the first major turning point in Southern politics, as conservative leaders in the South finally said they had enough and formed a new party to oppose both liberal Republican Thomas E. Dewey of New York and the sitting Democratic president, Harry Truman, who they charged was merely following Roosevelt’s big-government policies. The new State’s Right Party, called by some the “Dixiecrats,” named Democratic Senator Strom Thurmond of South Carolina as its standard bearer, and the party made its first real inroads into the Deep South’s solid Democratic wall by carrying the states of Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi and South Carolina. Even though these four states returned to the Democrat camp four years later, six other Southern states, Florida, Maryland, Missouri, Tennessee, Texas and Virginia defected to the 1952 Republican candidate, General Dwight D. Eisenhower. The next seismic shift in Southern politics was the 1964 contest between Republican Barry M. Goldwater and Democrat President Lyndon B. Johnson. While the Democrats overwhelmingly defeated Goldwater, most of the shots they fired at the conservative Republican, including the infamous atom bomb TV ad, were merely reloads of the ammunition used by liberal Republicans in their previous primary battles. Goldwater’s conservative message, however, hit home with many Southern voters, and the Republicans, in addition to Goldwater’s home state of Arizona, carried Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi and South Carolina. Four of these states, as well as Arkansas, voiced their conservative concerns at the ballot box again in 1968 by voting for the American Independent Party’s candidate, Governor George C. Wallace of Alabama. In addition that year, six other Southern states, Florida, Kentucky, Missouri, South Carolina, Tennessee and Virginia went into the Republican column for Richard M. Nixon.

The movement away from the Democratic Party continued throughout the South, with a number of leading Southern Democrats, such as Senators Strom Thurmond of South Carolina and Jesse Helms of North Carolina, crossing over to the Republican side of the aisle. This trend saw its culmination in the presidential election of 1972 when President Nixon’s “Southern strategy” helped him to carry every Southern state in his reelection bid. The only negative blip on the Republican radar in the South occurred during the following presidential election in which the weight of the Watergate scandal sank the campaign of Republican Gerald R. Ford. That year, every Southern state except Virginia returned to the Democratic camp and voted for Governor Jimmy Carter of Georgia, but four years later every state in the South except Georgia would reject Carter in favor of the conservative Republican, Ronald Reagan. In the thirty-five years since Reagan’s election, the “Solid South” has mainly remained a Republican stronghold. The rationale for this change, of course, lies in the virtually total reversal of America’s political poles, a tectonic shift in which the torch of conservatism that was once held high by 19th Century Southern Democrats is now being carried by today’s growing corps of conservative Republicans, while the Democratic Party has continued to adhere to the old Whig and Republican Party’s concepts of a more powerful and centralized federal government, weaker state’s rights and less popular sovereignty . . . just the reverse of the ideals which are still held dear by most Southerners. Therefore, what Barry Goldwater and his Southern followers attempted to bring to America a half century ago has finally come to pass, and it is quite certain that the Republican elephant will continue its stampede through Dixie just as long as the G. O. P. adheres to the South’s Jeffersonian principals and does not again fall victim to the siren song of those in the Party who espouse more liberal policies.

It must also, however, be borne in mind by everyone in America, be they Democrat, Republican or independent, that after the Roman Republic abdicated its power and became an empire, the seeds of Rome’s decline and ultimate fall were sown. A similar fate could well befall the American Republic if it casts aside the basic Southern concepts of republicanism and sovereign rights, and if its citizens continue to surrender their constitutional liberties in return for the modern-day equivalent of Imperial Rome’s largesse of bread and circuses . . . entitlements and subsidies.