On February 5, 1865, the last of General Sherman’s troops crossed the Savannah River into South Carolina. That same day, soldiers of the 14th Corps burned the village of Robertville. Determined to punish the “original secessionists,” an army of over 60,000 was now making its way through the Palmetto State on a mission of destruction and pillage.

On February 7, forces under the command of General Hugh Judson Kilpatrick burnt down most of the town of Barnwell. Some of the infantry troops encamped at the nearby plantation of Mrs. Alfred P. Aldrich. She wrote that one of the soldiers (“a wretch who looked as if he had been brought from Sing Sing for the purpose of terrifying women and children”) took one of her black servants, a man named Frank, and hung him by the neck to make him reveal the hiding place of Aldrich family valuables. When the soldier realized that Frank could tell them nothing, he let him down. “Frank’s neck remains twisted to this day,” Mrs. Aldrich reported in a post-war memoir.

Mrs. Aldrich also recalled the sight of Barnwell in ruins:

All the public buildings were destroyed. The fine brick Courthouse, with most of the stores, laid level with the ground, and many private residences, with only the chimneys standing like grim sentinels; the Masonic Hall in ashes. I had always believed that the archives, jewels and sacred emblems of the Order were so reverenced by Masons everywhere…that those wearing the “Blue” would guard the temple of their brothers in “Gray.” Not so, however. Nothing in South Carolina was held sacred.

After destroying Barnwell, General Kilpatrick joked that he had changed its name to “Burnwell.” Much of the town of Blackville was also torched by Federal forces on February 7, 1865.

On February 11, the town of Aiken was the site of a battle which was one of the last Southern victories of the war. Here Confederate General Joseph Wheeler defeated Federal cavalry under the command of General Hugh Judson Kilpatrick. General Kilpatrick’s men were forced to retreat, and Aiken was spared the destruction meted out to so many other places in the state.

James Courtney, a fifty-four year old civilian who lived near Aiken, was killed by Union troops while trying to save his house. The Aiken Press, a local newspaper, later recounted his story:

As Kilpatrick’s men moved towards Aiken, residents of the county realized that their worst fears were coming true. Mr. James Courtney determinedly extinguished three fires that the Union Cavalry had started to destroy his home. Each time Courtney extinguished the fire, the cavalry would restart it. After the third time, the cavalry shot him in the leg to prevent him from saving his house. Mr. Courtney sent a request for a Union surgeon to come stop the flow of blood, but the surgeon refused to come. James Courtney slowly bled to death while his home burned in front of him. Courtney, possibly, was the first casualty of Aiken County.

On February 12, about six hundred Confederate soldiers attempted to defend the midlands town of Orangeburg from the onslaught of Sherman’s army, but, overwhelmed by a vastly larger force, they were compelled to withdraw towards Columbia, and the Federals crossed the Edisto River and took possession of the place. Major Oscar L. Jackson of the 63rd Ohio Infantry Regiment recorded in his diary that the Federal soldiers who first entered Orangeburg found a store in flames, and claimed it had been deliberately set on fire by its owner, a Jewish merchant. “A fine breeze was blowing,” wrote Jackson, “and by the time we got into the town there was a big hole in the center of it and our boys rather assisted [the fire] than stopped its advance.”

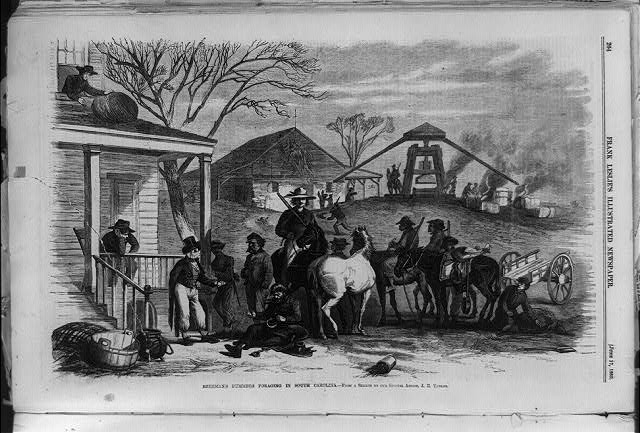

A townswoman watching from a building facing the public square, however, had a different view of how the fires started. From a window, she had seen a “blue-clad” soldier climb up to the roof of Mr. Ezekiel’s store and set it on fire with a torch (possibly one of the “bummers” who were almost always in advance of the main army). Her nephew, a young boy named Thomas O.S. Dibble, also watching from a nearby window, witnessed the town’s volunteer fire company, a group of old men and boys, trying to put out the flames, and then observed Union soldiers cutting the leather fire hose through which the firemen were pumping water.

Colonel Oscar Jackson noted in his diary on February 13: “Going through South Carolina we are burning nearly all buildings that will burn.”

The capital city of Columbia was the next target.