According to the standard narrative maintained by the North, Lincoln’s 1863 Emancipation Proclamation brought about a new moral aim that justified a particularly bloody conflict. The act is often described as a device that would usher in a new age where angelic Northerners suddenly abandoned their racist past in favor of a fair, more equitable course for enslaved men. From that point onward, the story goes, the highest Northern political officials were wholly devoted to the cause of abolition within the states.

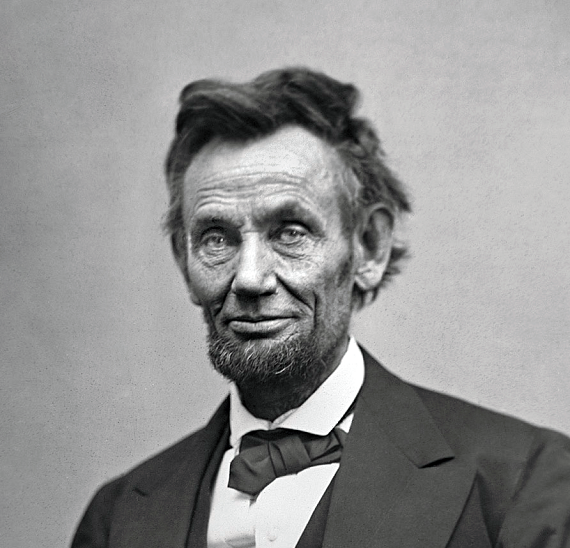

However, written records from this timeframe demonstrate a starkly divergent reality. Several significant circumstances from 1863-1865 illustrate that the most prominent leaders within the Union government, including President Abraham Lincoln and Secretary of State William Seward, were entirely willing to compromise on slavery. This case is most easily demonstrated by the events leading up to and including the Hampton Roads Conference of 1865.

The Union’s inclination to offer compromise on the issue of slavery truly began with the proposed Corwin Amendment of 1861, but resurfaced in the year prior to the conference. In late 1864, Seward opined that if the seceded states abandoned their quest for independence, the matter of slavery would fall entirely to “the arbitrament of courts of law, and to the councils of legislation.” Even Lincoln’s own cabinet admitted the proclamation was an arbitrary act, acknowledging that it would be ripped to shreds and ruled unconstitutional by the same federal court that declared his suspension of habeas corpus to be a blatant constitutional violation. While Lincoln defied that opinion anyway, many thought he lacked the political capital or enforcement resources to resist court judgment against his famous executive edict. Republicans in Congress responded by drafting the eventual 13th Amendment, which would effectively trump any federal court ruling that negated Lincoln’s decree.

The most noteworthy attempt to end the war through a peaceful reconciliation, the Hampton Roads Conference was attended by representatives from both governments. Lincoln and Seward arranged for a clandestine meeting upon the River Queen, a newly built steamboat docked at Hampton Roads, Virginia. The Confederate delegation was comprised of Vice President Alexander Stephens, Senator Robert M. T. Hunter, and Assistant Secretary of War John Campbell. Both sides had cause to entertain the prospect of a peaceful resolution. Lincoln still faced enormous political opposition in the North from Copperheads, who professed that war against the South was unnecessary and unconstitutional. In addition to this, some of Lincoln’s closest friends, including Francis Blair, strongly urged him to attempt for an amicable end to the bitter struggle. For his part, Stephens remained consistently devoted to ending the war since 1863, believing that Robert E. Lee’s military successes of that year could convince the North to reach a settlement that recognized the independence of the Confederate States of America. By this time, William Sherman’s bloody path of destruction had consumed South Carolina and Georgia, resulting in widespread property destruction, looting, and civilian death.

During the conference, both Lincoln and Seward made several proposals assuring protections for slavery in return for a peaceful reunion of the Southern States. Lincoln admitted that the Emancipation Proclamation was perceived as a temporary war measure, and disclosed that federal courts may well render it unconstitutional.[1] Conceding that the Proclamation was not actually as morally grand as many historians now claim it to be, Lincoln downplayed its political significance in an attempt to garner Southern favor. At one point, William Seward produced a copy of the pending Thirteen Amendment, which had not yet been ratified, and postulated that Southerners could prevent its codification through a reconstructed Union. Lincoln added that the other caveats may be added specifically for Southern States, such as giving Georgia an ability to ratify with a five year delay.[2] As another olive branch, Lincoln suggested that a fiscal compensation for emancipation would be considered by the federal government, naming the prospective amount of $400 million. Lincoln showed earnest commitment to this offer, suggesting the same figure to Congress after the conference.[3] The one topic of paramount importance to the South that the Union stubbornly refused to entertain was the prospect of Southern independence and the recognition of Southern secession. On these subjects, Lincoln was unwavering and uncompromising.

Some Lincoln defenders have supposed that the accounts by Stephens and Campbell were erroneous and concocted fallaciously, but this view does not withstand sincere scrutiny. Outside of the notes recorded by Stephens and Campbell, Lincoln’s written correspondence corroborates his willingness to negotiate on the matter of slavery. During this timeframe, Lincoln wrote that he would be willing to leave “slavery to abide by the decisions of judicial tribunals,” and that slavery “shall not stand in the way of peace.”[4] Prominent Seward biographers, including Frederic Bancroft, have also agreed that the Secretary of State assured the commissioners that the South could reject the 13th Amendment. Bancroft wrote that Seward “at least suggested” that the seceded states could “defeat the adoption of the amendment” through a speedy return to the union.[5]

Perhaps most significantly, the Union Congress, which had been debating the proposed 13th Amendment, responded with the alarm to the Hampton Roads Conference. When news of the event broke out, many representatives felt that a positive affirmation of the amendment would undermine the potential for a peaceful resolution with the South. If Lincoln wished to, he could have acknowledged the conference, denied that any concessions on slavery were offered, and added that the convention was concluded and effectually useless. Instead, he denied any talks of peace with Confederates in Washington (the conference had actually occurred in Virginia), a deceitful way to circumvent the issue and conceal any attempt by his administration to compromise on slavery.

In sincere abhorrence, Confederate President Jefferson Davis immediately renounced the conference, and insisted that the Confederacy must continue fight on because Lincoln refused to recognize an independent Confederate government. Indeed, it was Lincoln himself that admitted this fact. On the most significant point of contention between the two countries, he told Congress that Davis “would accept nothing short of severance of the Union – precisely what we will and cannot give.”[6] Davis’ stance echoed an earlier attempt at peaceful negotiation, and validated the unswerving yearning of the South. In 1863, Davis wrote Stephens a letter which articulated that a successful compromise between the two countries could only be ascertained if Lincoln recognized the legitimacy of the Confederate government. “Such a conference is admissible only on the footing of perfect equality,” he wrote. In the event that this could not be acknowledged, Seward was to “decline any further attempt to confer on the subject” of his mission.[7] While the letter’s potential was negated by the Battle of Gettysburg, its prose captured the Confederacy’s chief aim and made its purpose unmistakable. Of course, the note did not mention the supposed desire to extract slavery assurances from the Union.

Lincoln’s concessions on slavery should be unsurprising to earnest students of history, who knowingly acknowledge Lincoln’s continual insistence that he lacked the constitutional authority to end slavery in the states. They must also recognize Lincoln’s widely publicized support for the Corwin Amendment, which would have protected slavery through constitutional amendment for all time. Far from treating slavery as an issue worth fighting a bloody conflict over, Lincoln’s principal objective was to suppress Southern secession efforts, eliminate Southern independence, and eradicate the federal political system the South solemnly desired to maintain. If anything, history proves that Lincoln considered slavery as nothing more than a political bargaining chip.

If we seek to eschew the notion that the entire history and heritage of the South is confined to a four year period, the century-spanning cause of Southern independence should be elevated above and emphasized over petty attempts to demean it. By the traditional narrative, the South should have been willing to jump at the prospect of ending the war in return for the numerous concessions on slavery – but it didn’t. By typical accounts, Confederate officials should have gladly abandoned their aspirations for independence to preserve human enslavement – but they didn’t. According to most textbooks, Lincoln was more interested in abolition than the forceful suppression of secession – but he wasn’t. In the standard tale, Lincoln and his cabinet adopted a newfound, moral commitment against slavery that replaced all previous motives for waging a particularly bloody war – but they didn’t.

Ultimately, the Confederacy was unwilling to reach a compromise with the North if Southern sovereignty and independence could not be guaranteed. With these factors as their highest prerogatives, the Southern States were equally unwilling to waver from their initial position. While Lincoln attempted to appeal to Southern interests through slavery concessions, Stephens and the other Confederate delegates considered those matters minute in comparison to their highest objectives. These men believed that Southern independence, decentralized government, and personal liberty were truly worth fighting for. Any feeble and dishonest attempt to substitute slavery in place of these maxims would pervert the true Jeffersonian tradition that the South adopted and cherished.

[1] Ludwell Johnson, “Lincoln’s Solution to the Problem of Peace Terms, 1864-1865,” The Journal of Southern History, 34 (November 1968), 581.

[2] Ibid, 582

[3] Ibid, 582-583.

[4] Quoted in David Donald, Lincoln (New York: Simon & Schuster), 559.

[5] Quoted in Paul Escott, What Shall We Do with the Negro? (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2009), 211.

[6] Annual Message to Congress, December 6, 1864, in The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Edited by Roy Basler (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1955), Volume 8: 151.

[7] Jefferson Davis to Alexander Stephens, July 2, 1863, in The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government (Cambridge: De Capo Press, 1990), Volume II: 501.