The United States Constitution does not contain the words “separation of church and state,” nor does it require the general government to purge all religious influence from public institutions. To the contrary of modern conceptions, the document does not require that elected officials abstain from making decisions based on religious proclivities, nor does it call for government to intervene to prevent religious influence in government.

It does, however, affirm the natural right of free religious association and prevents the general government from “respecting the establishment of religion.” Additionally, the Constitution prohibited religious oaths of affirmation, a classic form of governmental religious discrimination, from being imposed upon civil officials. Evident from the ratification struggle, this baseline was meant to encourage religious practices, especially by those held by religious minorities. Since genuine effort was taken to hinder the government from religious interference and persecution, those of all theistic persuasions would be able to worship freely, whether they served in government or not.

Despite this truth, much ire has been generated among those who believe public figures should discard their religious predilections entirely while in office, or refrain from using religious stances to influence their voting patterns or political stances. While failing to recognize contextual cues, some adopt the purely mistaken perception that “separation of church and state” was meant to discourage religious practices or remove them from the public arena entirely.

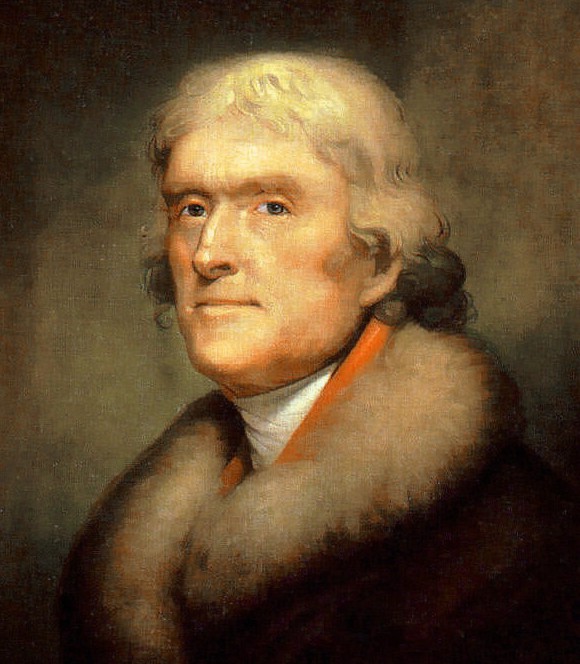

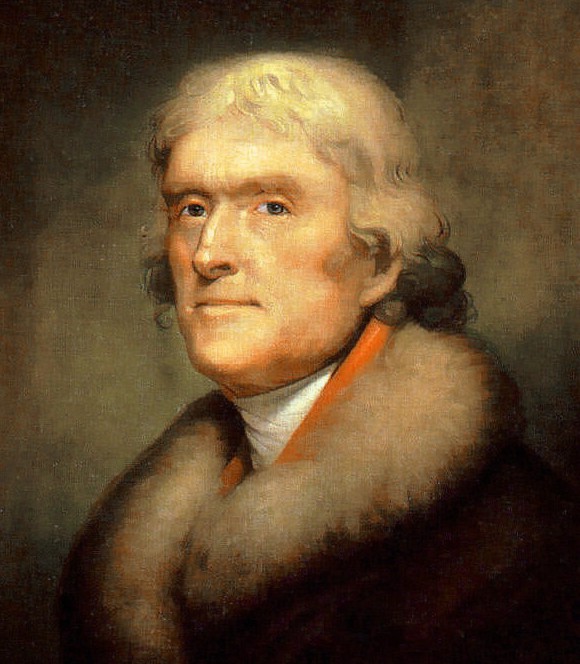

The words of this now-famous phrase come from a Thomas Jefferson letter to the Danbury Baptists in 1802. As an extremely small religious minority, this group inquired as to whether the president would stick to his principles by refusing to impose religious barriers that would prevent religious minorities from obtaining positions in government. Jefferson’s candid answer was that government’s inability to intervene in the religious practices of individuals was what built a “wall of separation” between church and state. Because of this conciliatory gesture, Jefferson established popularity with other Baptists throughout the states. The most famous Baptist minister of the day, John Leland, responded to Jefferson’s commitment by organizing a group of adherents in Cheshire, Massachusetts, to create giant block of cheese, which Leland personally delivered to the presidential mansion. While in Washington, Leland was invited to preach to the Congress and the president.

Regardless of the historical record, the modern perception of the phrase has been warped, maligned, and reinterpreted by those who adhere to a fallacious understanding of Jefferson’s guarantee. Without investigating the context, many conclude that their own ideal notions should override the empirical essence of Jefferson’s leanings. Contrary to these contemporary tendencies, Jefferson was not advancing the contemporary view that religion should be expunged from public life, but instead expressing the belief that government should not involve itself in religious matters.

Contrary to the standard narrative, the United States Capitol building once served as an actual church on Sundays, where prominent politicians and several presidents, including Jefferson himself, attended services – a practice that lasted until after the Civil War. Many of the states had official state churches, even into the 19th century. Massachusetts, for instance, disaffiliated its connection with the Congressionalist church in 1833. None of the founders, even non-clerical worshippers, made the insinuation that a man in government should divorce himself of his own religious convictions.

When the new government formed under the Constitution, the First Congress implemented a chaplain system where officials of different denominations were appointed. The chaplains had a salary, and the practice continues today. How could this be, under the modern misrepresentation of Jefferson’s sentiments? While the founders did not aim to create a national theocracy, they certainly did not endeavor to impede the natural extension of religious influence into the realm of government. Realizing that religious beliefs would impact the outlook of elected representatives, doing otherwise would have violated the spirit of free exercise that religious liberty was premised upon.

Jefferson’s words on this matter were widely understood for most of American history, and did not become a transformational political tool until the 1947 Supreme Court case of Everson v. Board of Education. In that case, Justice Hugo Black misrepresented Jefferson’s original words, and used them as justification to incorporate the First Amendment as limitations against the state governments as well. This was done on the basis of the “incorporation doctrine,” an unsubstantiated legal view that the 14th Amendment incorporated the Bill of Rights limitations against the states as well as the federal government. The incorporation doctrine notwithstanding, the actual meaning of any constitutional amendment is not subject any particular individual’s perspective, but instead the spirit of how that amendment was accepted by the states that ratified it.

Moreover, the First Amendment was written and ratified more than a decade prior to Jefferson’s usage of the phrase. Even if Jefferson’s words in 1802 were the ultimate scope through which the First Amendment should be understood, Justice Black embraced a fraudulent narrative based on mistaken premises. Becoming the first to claim that Jefferson’s words justified federal intervention in the state churches 150 years after ratification of the Constitution and the First Amendment, Black was simply incorrect.

Jefferson lived in the world that was only a century removed from the Glorious Revolution of 1688, where England’s King James II endeavored to inject his contradictory religious beliefs into the country’s Anglican churches. Through The Declaration of Indulgence, each Anglican congregation was forced to read a royal proclamation that summarized the king’s position on England’s Test Acts. This was perceived as an illegitimate violation of religious liberty, as the king attempted to intervene in the religious practices of his subjects. Parliament responded by making calculated strides to undermine the king, eventually inviting William of Orange to invade England and take the throne. Beyond this incident, religious minorities also suffered immensely throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, namely Puritans and Catholics. England’s Act of Supremacy forced all public officials to swear allegiance to the monarch as the head of the church. Failure to do so would cause officials to be indicted on charges of treason, establishing an era of institutionalized religious persecution.

Hoping to secure religious liberty on a local level, Jefferson and Madison rightfully opposed the existence of a state church and religious subsidization. Matching their penchants with steadfast actions, they worked diligently to abolish Virginia’s connection to the established Anglican Church through the passage of the Virginia Statue For Religious Freedom. While Jefferson wrote and introduced the bill in 1777, it was not until Madison worked tirelessly to push the law through Virginia’s legislature that the policy was realized in 1786. This forerunner demonstrated that both men were truly committed to religious liberty, and the ability of religious people to become civil officers. Through this effort, both men sought to avoid the mistakes of England’s past.

Since the Baptists found themselves in opposition to their own state’s established church, Jefferson naturally sympathized with them and provided them with a solemn assurance. The “wall of separation” he proposed clearly intended to prevent government from intervening in religion, not to disbar religious influence in government. He did not aspire to eliminate religious practices or religious principles, he aimed to encourage them. To twist Jefferson’s words simply to fit into one’s own preferred narrative is, in my estimation, a disingenuous affair that requires a significant neglect of actual history.