In present day academia, one is guaranteed a celebrated career by inventing a new way to put the South in a bad light or a new twist on an old put-down. In the 1970s, Raimondo Luraghi, Eugene Genovese, and other historians were starting to pay some attention to the existence of a genuine aristocratic ethics in the Old South. Immediately a C. Vann Woodward student stepped into the breach and produced a book on “Southern Honor.” Now we would suppose that a book on Southern honor would have something to say about George Washington and Robert E. Lee and devotion to duty. Not a bit of it. “Southern honor,” it seems, is just a dishonest excuse for some backward folks in East Tennessee to suppress their non-comforming neighbours. Honour in the South is not what Jacob Burkhardt defined as an enigmatic mixture of ethics and ego; it is all about brawls and peasant chivarees. This same historian a few years later essayed a presentation on how Confederate soldiers were not really brave. A graduate student who actually knew something about the subject politely took him apart limb by limb.

A little later, historians doing genuine research in the sources were starting to find out interesting things about antebellum Southern women. It seems they were not simpering idiots after all but an extraordinary number of them were intelligent and strong persons who managed important affairs and even wrote books. Not to worry. Another Woodward student rushes into the breach along with some others and we soon have a new bevy of chair professors of Southern history celebrated for their insightful discoveries. It is now the standard interpretation that these women, since they were strong and intelligent, must have been feminists. Clearly they had to be in secret revolt against the brutal oppression of the Southern white male ruling class, which they could not possibly have approved of our identified with. After all, some of them sometimes complained about their husbands and the hardships of war. That this is a ludicrous misreading of the evidence and of human nature does not prevent it from being orthodoxy.

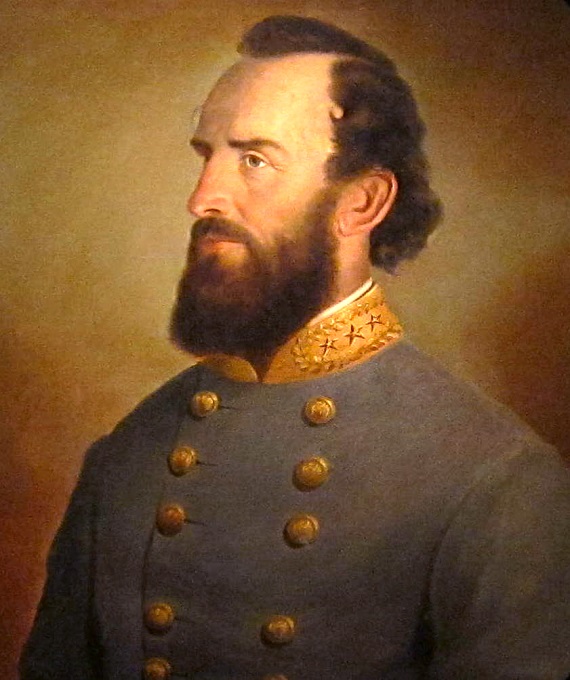

A little later notice began to be taken of unprecedentedly brutal aspects of Yankee proceedings in the War to Prevent Southern Independence. Never fear, another champion of fashionable orthodoxy steps into the breach. It seems that total war was initiated when Stonewall Jackson urged relentless force against the enemy. Stonewall Jackson’s advocacy of harsh response to invading soldiers, which was never actually implemented, thus becomes the cause of and the moral equivalent of the Union’s officially authorized, systematic, and pervasive terrorism against Southern civilians. Another celebrated book.

I could pile up these examples for pages, but you get the idea. If we are going to know the South we need to look at the thing itself, not through the dark lenses with which we have been provided. Perfection can never be achieved in that or in any historical understanding, for our knowledge of the past must always be subject to re-examination in the light of evidence and new perspectives. But by studying the South as itself we can get closer to the truth than has been done by the mainstream intellectuals. And it is important that we do so. It is our people and our culture that we are dealing with here. Our people are not without their good points; and we have a right to our past, which is a part of claiming the right to our present and future. Further, if the story of the South is not told with truth, the story of America remains perilously distorted.

After the War Between the States, the Georgia author Charles Henry Smith (“Bill Arp”) was invited by a Northern publisher to renew writing for his prewar Northern readers. He did so and took the occasion to inform those readers of the evils of Reconstruction. “Reconstruction” was being excused by the Radical Republicans by a claim that the South was still dangerously rebellious. Smith remarked that Southerners were “conquered but not convinced,” but that they had given their word that they accepted defeat in good faith: “Southern honour, which our enemies cannot appreciate, but which is untarnished and imperishable, is the seal of our good faith.”