John Cussons had enough. It was 1897, and for thirty-two years he had watched as “Northern friends of ours have been diligent in a systematic distortion of the leading facts of American history— inventing, suppressing, perverting, without scruple or shame—until our Southland stands to-day pilloried to the scorn of all the world and bearing on her front the brand of every infamy.” The South had sat silently, watching as the North explored every avenue to disparage her people, her cause, and her history. In the short period following the War, Northerners had painted the South as the personification of “meanness,” “folly,” and “utter and incurable inefficiency.” The South was the despicable “other” in the American mind, and as a result “The economist with a principle to illustrate, the moralist full of his Nemesian philosophy, the dramatist in quest of poetic justice—in short every craftsman of tongue or pen with a moral to point or a tale to adorn turns instinctively to this mythical, this fiction-created South, and finds the thing he seeks.”

This had broken the unwritten agreement between the two sections following the War. Northerners would acknowledge Lee and Jackson as great Americans and in return the South would consider Lincoln to be the man of hour who saved the Union.

And the South had come to accept it. Her people had been turned against their own history, brainwashed into believing the Yankee version of American history, a history fabricated in the years following the great Southern struggle for independence. Southern children were the targets and as a result “our grandchildren, trained in the public schools, often mingle with their affection an indefinable pity, a pathetic sorrow—solacing us with their caresses while vainly striving to forget “our crimes.” A bright little girl climbs into the old veteran’s lap, and hugging him hard and kissing his gray head, exclaims: ‘I don’t care, grandpa, if you were an old rebel! I love you!'”

This could have been said today.

Cussons understood one of the great maxims of history by quoting the great British historian Lord Macaulay, “a people which takes no pride in the noble achievements of a remote ancestry will never achieve anything worthy to be remembered by remote descendants.” The systematic destruction of the Southern tradition by distortion and lies would render her people impotent in the future. His words were more than quaint “unreconstructed” rants against the government. They were not “I’m A Good Ol’ Rebel.” Cussons wielded a philosophical hammer against Yankee Puritanism in an attempt to save the South from self-loathing, guilt, and shame.

Cussons knew the South, the real South, still existed. It had been defeated in war, but the Southern people had much to admire in their history. Her heroes defended a noble tradition and that tradition, if correctly articulated and saved, would place the South at its proper place in the forefront of American history. Unfortunately, his double-barreled assault on Yankee distortion has been mostly forgotten. His two short works defending the South are not placed among the great tomes of the late post-bellum period primarily because not many know they existed. United States “History” as the Yankee Makes and Takes It and its more substantial sister A Glance at Current History are clear, concise, and more importantly caustic. They are as witty as Bledsoe’s Is Davis a Traitor? or Taylor’s Destruction and Reconstruction and while not as meaty as Stephens’s or Davis’s multi-volume masterpieces on the War and Southern history offer the same defense.

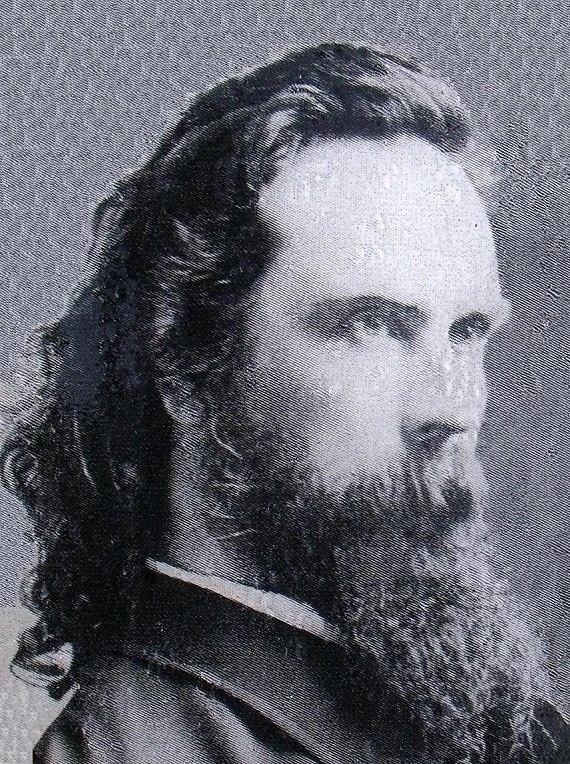

Cussons was born in England and emigrated to North America in 1855. He lived for four years among the Sioux in the Northwest where they named him “The Tall Pine Tree.” He moved to Selma, Alabama in 1859 and became a newspaperman as the half owner of the Morning Reporter. He opposed secession but when the War began in 1861 he served as a commander of scouts and sharpshooters in the Army of Northern Virginia. He was captured at Gettysburg and after his release spent the remaining months of the War out Western theater, eventually fighting with Nathan Bedford Forrest. Following the War he founded a publishing firm, owned a large hunting lodge in Virginia, and served as one of the officers of the United Confederate Veterans.

United States “History” as the Yankee Makes and Takes It was a short work designed to illustrate the growing problem of Puritan history in America. The Puritan, Cussons argued, always considers himself to be the moral superior to any other people. From the beginning, Puritans had formulated the false notion that their customs and traditions produced better men and societies than those of the South. For example, the “Yankee” or “Puritan” idea would logically “formulate and demonstrate” the following proposition:

“1. Patrick Henry, furnished with a good stock of groceries, failed at twenty-three.

2. A Puritan, even of the tenth magnitude, under like circumstances, would not fail at twenty-three.

Ergo: A tenth-rate Puritan is the superior of Patrick Henry.”

This, of course, is a fallacy in logic but one that makes perfect sense to the New England mind.

Cussons defined the Yankee as thus:

Self-styled as the apostle of liberty, he has ever claimed for himself the liberty of persecuting all who presumed to differ from him. Self-appointed as the champion of unity and harmony, he has carried discord into every land that his foot has smitten. Exalting himself as the defender of freedom of thought, his favorite practice has been to muzzle the press and to adjourn legislatures with the sword. Vaunting himself as the only true disciple of the living God, he has done more to bring sacred things into disrepute than has been accomplished by all the apostates of all the ages, from Judas Iscariot to Robert G. Ingersoll. Born in revolt against, law and order—breeding schism in the Church and faction in the State—seceding from every organization to which he had pledged fidelity—nullifying all law, human and divine, which lacked the seal of his approval—evermore setting up what he calls his conscience against the most august of constituted authorities and the most sacred of covenanted obligations, he yet has the impregnable conceit to pose himself in the world’s eye as the only surviving specimen of political or moral worth.

He questioned American education, the attempt by the general government–more importantly the Union veterans of the Grand Army of the Potomac–to write a “true” history of the War, and the false narrative that the North had long been opposed to the principles of States’ rights, nullification, and secession.

At every step, Cussons defended the men and the cause of the South and lamented that her history was being written by the victors. “The whole story of the war and its causes,” he wrote, “has been distorted and perverted and falsely told. Yet at the bar of unbiased history, before the tribunal of impartial posterity, it will become manifest that the vital principle of self-government—the world’s ideal, and what was fondly deemed America’s realization of that ideal—went down in blood and tears on the stricken field of Appomattox. It was there that Statehood perished. It was there that the last stand was made for the once-sacred principle of ‘government by free consent.'” The old republic of the founding generation was buried by Puritanical self-righteousness. Cussons predicted the inevitable outcome:

Potential classes are now longing for a change; they are earnest in their desire for what they call “a strong government.” And it may be that their yearnings will not be in vain. The corruption of a republic is the germination of an empire. A period of domestic turbulence or foreign war would render usurpation as easy as the repetition of a thrice-told tale. Political speculations would then reassume their old names—incivism, sedition, constructive treason—and the familiar remedies would be applied—press censorship, the star chamber, lettres de cachet, and bureaus of military justice.

In the final chapter of A Glance at Current History, Cussons addressed the relationship between the Indian tribes and the general government and compared the plight of the Indian–harassed, chased, threatened with extermination–with that of the South during and after the War. He recoiled at their treatment and bristled at attempts to make them “good people.” How would it sound, he asked, if the Indian said in response to the bloodthirsty General Philip Sheridan that, “There is no good Yankee but a dead Yankee?” Like the South, the Indian had a noble heritage that was being trampled by an invading army. Cussons believed the two shared a common cause.

Cussons’s firmly argued essays provided a needed balance to the transformation of American history in the early twentieth century and in our own time as well. They are indicative of a larger effort to save what was left of the traditional South, both culturally and politically, for Cussons saw his section as the last hedge in a great struggle for liberty and self-government. It still must be so.