When the Scottish Parliament voted to join the English Parliament in 1707, it seemed the end of Scottish national identity. It was thought that a small country like Scotland could not succeed economically without being politically integrated into a powerful trading country like England. This gave rise to a “small country” versus “large country” debate.

Out of this debate,the Scottish philosopher Adam Smith published The Wealth of Nations which argued that in a system of free trade, small countries could flourish by utilizing their comparative advantage. And he was right.The top 10 countries in per capita income in 2013 were small: Norway, Luxembourg, Hong Kong, Singapore, Liechtenstein, Qatar, Bermuda, Monaco, Jersey, and Brunei.The United States was ranked 12th.

There is no reason that Scotland, with some 5 million people, cannot be one of the richest countries in the world, like her northern neighbor Norway, which is not only wealthy but has wisely stayed out of the European Union, something the Scottish National Party foolishly seeks to join if independence is achieved. This is the same mistake their ancestors made in 1707 by joining England.

Scotland did not lose its national identity by being incorporated into the English Parliament. It was allowed to keep its religion and its law which was Roman and Dutch. But most importantly its culture survived. Andrew Fletcher of Saltoun told his countrymen who feared losing their national identity because they had lost their parliament: “Let who will write the laws, as long as I can write the songs.”

This was born out in the early 19th century when Scottish identity was being ground down by the industrial revolution and endless prattle about progress and global liberalism. On the scene appeared the novels of Sir Walter Scott who discovered virtues in medieval Scotland which had been ignored by progressives. Not only did Scott’s novels revive Scottish national identity and pride in their ancestors, readers around the world took an interest in Scotland. The movie Braveheart has had a similar effect. Scots of my generation attended weddings and funerals in suits. Today young Scottish men attend them in kilts.

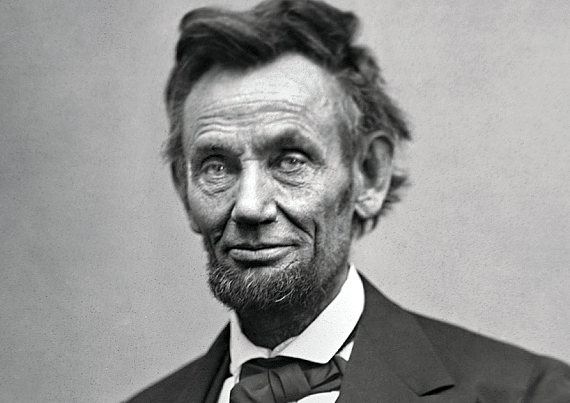

This revival of historic cultural identities long thought to have been hollowed out by massive, centralized modern states built after the French Revolution has subverted the superstition that the modern state is “one and indivisible.” Nothing made by mortal man is indivisible,and certainly nothing political is indivisible. The idea that modern states are indivisible is a 19th century prejudice as outdated as their stove pipe hats, hoop skirts, and physics which said the atom is indivisible.

Throughout Europe serious secession movements are reversing the post-French Revolutionary trend of mindless centralization. Catalonia, the Veneto and Lombardy in Italy, Bavaria in Germany, Corsica, and other peoples throughout Europe, who have stubbornly maintained their cultural identities, seek self-government either through more regional autonomy or through secession and political independence.

It does not matter whether Scotland votes “yes” or “no.” Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, through the secession of 15 states, the modern state has been losing the mystique of indivisibility. If the vote is “no,” a future referendum is always possible. We should reflect on this when we pledge allegiance not to the Constitution, but to a “flag” said to represent “one nation, indivisible.”