This article was originally published at lewrockwell.com.

In all the recent fuss over symbols of the Confederacy, whether to honor them or get rid of the lot, not much attention has been paid to what that Confederacy was, after all, and why it might be something that anyone would want to commemorate.

Of course one side doesn’t care. It is sufficient for them that among the attributes of that government was a devotion to the defense of slavery, and about that there is no possibility of rational discussion or gradations of judgment. What difference do any other attributes make?

And the other side is not very articulate about why the Confederacy matters any more, except to say that their ancestors fought nobly for it back then and they should still be remembered today. And getting excited about a lot of people dying a century-and-a-half ago, no matter how honorably, doesn’t seem all that important to many people today.

But I have just come back from a conference sponsored by the Abbeville Institute at Stone Mountain Park in Georgia, devoted to discussing what one speaker called “the cultural genocide being waged against the South,” during which a number of speakers made very clear what the Confederacy represents and why it is still important for us—all of us, regardless of region or color—to remember today.

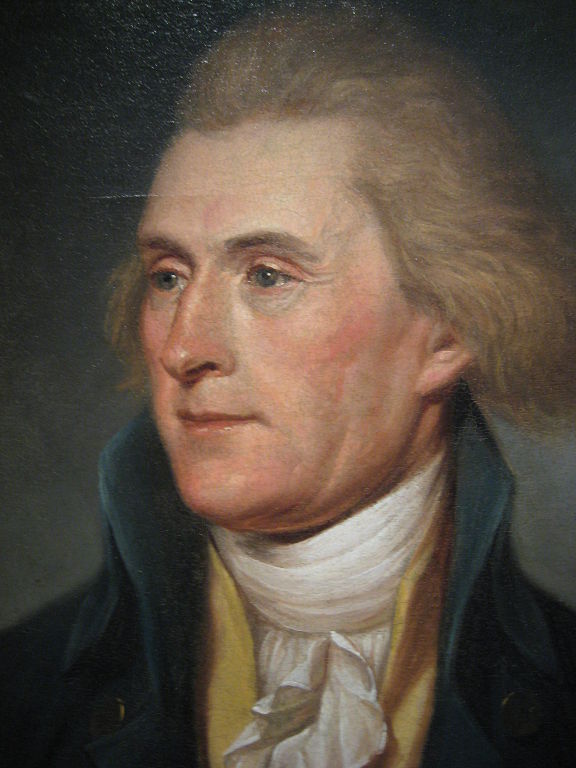

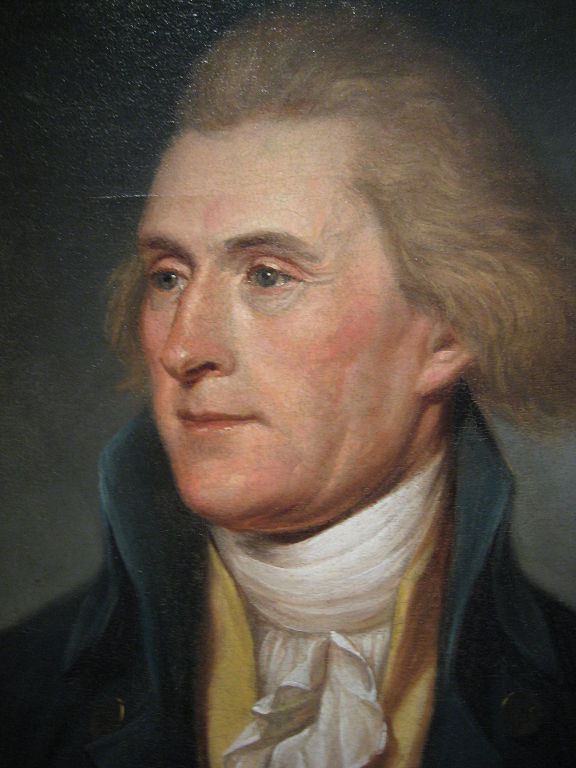

Perhaps the first theme that emerged was that the Confederacy was in its inception—and could still stand for us today—as an embodiment of the Jeffersonian vision of an America, in which states’ rights would predominate, the powers of the central government were prescribed and proscribed, and political and economic life would remain closer to the human scale. This stood in sharp contrast to the Lincolnian vision just then being thrust on the nation by the Republican Party, which stood for the consolidation of central power, the use of that power to the ends of the industrial and financial interests of the North, and the accession of the states to the increasing reach of Washington, particularly over “internal improvements,” especially transportation infrastructure.

These were significant differences, and if not often spoken aloud were definitely in the minds and hearts of both camps in the period before the war. So important was the perpetuation of the Jeffersonian vision to the South that the Confederacy began its constitution with the declaration “We, the people of the Confederate States, each state acting in its sovereign and independent character,” a ringing assertion of state sovereignty in sharp contrast to the original Constitution’s more general idea of “We, the people of the United States.” Indeed, it was the failure of the U.S. Constitution to spell out state sovereignty that led people like Lincoln to postulate that the states were no different from the counties in a state, creatures of the government and obedient to its dictates.

The Confederate constitution, reflecting the character of its people, was also explicit in “invoking the favor and guidance of Almighty God,” a sentiment absent from the U.S. Constitution. As difficult as it may be to believe in this day and age, it was an appropriate sentiment and sentinel for the Southerners of that time.

A second vital theme was the role of the Confederacy in resisting the attempts of the North to dominate the South, in upholding Southern rights. In particular, it resented the usurpation of Southern tariffs for three-fourths of the U.S. budget, which largely went to foster the industrial interests of the North in the antebellum years—and that is why the Confederate constitution was careful to spell out that its congress was forbidden to appropriate money “to promote or foster any branch of industry” so that the Confederate government could never treat the South as the national government had. Not only were the states sovereign, but the Confederacy was sovereign, no longer under the Northern thumb.

All that explains better than any monument can convey the reason that so many Southerners of military age were ready to sign up for a war of resistance to Northern invasion—unlike Northerners, who readily avoided service and forced the Union army to rely so heavily on foreign mercenaries and black regiments. It explains also why today there are still so many people who invoke the memory of the Confederacy and the principles for which it was formed. It may have served to perpetuate the sin of slavery, which after all was the basis of its prosperous economy, but it stood for far more than that.

It stood for values that are worth having statues and memorials and street names and ceremonies for.