Expert testimony in several federal court cases:

Scholars in every field in the humanities and social sciences have long recognized that Southerners have formed a distinct people within the body of Americans from the earliest colonial times to the present. Authorities in history, political science, economics, sociology, folklore, literature, geography, speech, and music, have recognized and studied the significance of this distinctiveness. The distinct identity of Southerners has also, of course, been a commonplace of everyday life in the United States, and distinctive Southern manners, customs, attitudes and behavior have been material for our greatest creative artists in song, story and movie-making.

Nearly every college in the United States and many in Europe (as well as Japan and Australia) offer courses in Southern history, literature, and other subjects. A number of universities have special institutes devoted to study of the South. (The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, the University of South Carolina, the University of Mississippi, John Hopkins University, and Cambridge University are a few examples.) Thousands of scholars around the world are studying Southernness. Thousands of books and dozens of popular and academic journals and websites are available today that are devoted specifically and exclusively to the South. It cannot be credited that this activity would be devoted to something unless it was real and significant.

Many explanations and descriptions have been offered in scholarly literature as to the origins and nature of a distinctive Southern people, beginning with the ethnic origins of the American colonial population and coming up to recent date in studies of public opinion and voting behavior.

An important, recent and authoritative study is Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America by David Hackett Fischer, prize-winning Professor of History at Brandeis University, Boston (New York: Oxford University Press. 1989). From exhaustive study in Britain and America, Fischer has identified four different cultural groups from the British Isles that formed differentiated cores of cultural development in what has become the United States. These groups came from different regions of Britain and were separated by religious denomination, economic activity, dialect, manners, and customs.

1) Puritan settlers of New England who came from the East Anglia region of England and formed an identifiable religious and cultural group, which spread to other parts of the Northern states.

2) Settlers from the English Midlands and Wales who settled the Delaware River Valley, belonged to a variety of dissenting religions such as Quakers and Baptists, and pursued economic activities and goals different from those of New England and the South.

3) Gentry and servants from the English southern counties who settled Virginia and the Carolinas in the 17th century, largely Anglican, engaged in plantation agriculture, and displaying manners, customs and attitudes very distinct from groups 1 and 2.

4) Borderers, sometimes loosely described as Celtic, who came from Ireland, Scotland, and the Scots-English border region. They were largely Presbyterian and their ways of living and making a living were markedly different from those of the ordinary English. They settled the Piedmont regions of the Southern colonies and spread across the Appalachians in the late 18th century.

Fischer piles up convincing data that these groups formed different cultural centers in the evolution of America. Groups 3 and 4 merged in the early 19th century, to become the Southern people. The distinctiveness of a Southern people was well recognized by everyone by that time—by Southerners, by Northerners, and by foreign travelers. The famous English writer Charles Dickens observed after a trip to America that the Americans formed two distinct peoples. Fischer also provides extensive and convincing evidence that these distinct American cultures persist to this day, a distinctiveness, which can be seen in attitudes, political behavior, and daily life. An interesting example he provides is the startlingly different actions and methods of leadership of two American generals in the Pacific theatre during World War II, both named Smith, one from the North and one a Southerner. Countless other examples can be cited showing such differences in recent history.

Historians have also identified as keys to Southernness climate and a historical experience that differs markedly from the general American. The South was warmer than the North and the regions of Europe from which settlers of America came, giving it a different kind of agriculture and crops (cotton, rice, tobacco, sugar), and thus a different kind of economic activity and a different relation to the marketplace than the rest of the United States. When the U.S. Department of Agriculture decided in the 1920s to commission a definitive history of American agriculture, it found that it required two distinct studies to cover the subject: Percy W. Bidwell, History of Agriculture in the Northern United States, 1620-1860 (Washington: 1925), and Lewis Cecil Gray, Historyof Agriculture in the Southern United States to 1860 (Washington: 1933). Southerners have, unlike other Americans, more than 350 years of living in a biracial society, in which whites and African-Americans have reciprocally influenced each other’s development. It should never be forgotten that the number of African-Americans outside the states of the South was statistically insignificant throughout American history up to World War I. In evidence of a distinct Southern culture, it should be pointed out that Southern African-Americans share with Southern whites nearly every aspect of Southern culture except ethnic origin and political behavior, and differ from general American attitudes in the same direction as do white Southerners.

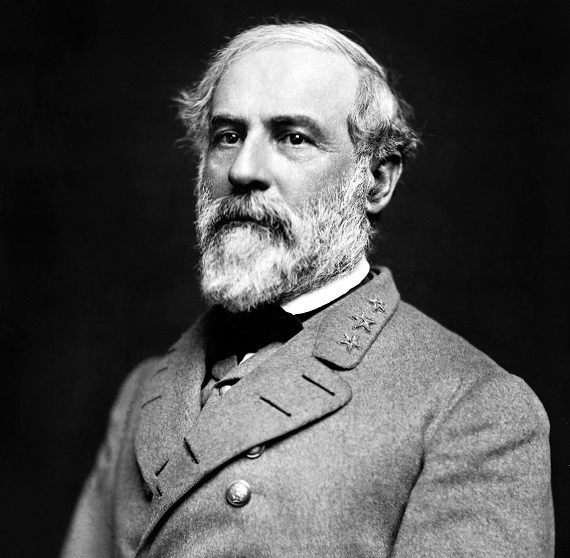

Undoubtedly the most decisive historical event in firmly establishing a Southern people was the failed War of Independence of 1861-1865. Unlike all other Americans, Southerners have suffered military defeat and occupation and massive destruction by invading armies on their soil. The Confederate States of America was characterized by a mobilization and casualties far beyond that ever experienced by any other Americans at any time in their history. (Gary Gallagher of the University of Virginia, The Confederate War, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997.) It is estimated that 85 percent of the eligible male population was mobilized in the War of Independence and one of every four Southern white men was dead at the end of the War. (Comparison: Northern losses were 1 in 10; and the loss was simultaneously made up by immigrants. American losses in later years are trivial percentages in comparison.) The experience of total war, invasion, conquest and defeat had effects, both tangible and psychological, that have lasted for generations and that mark Southerners now living. War is the single greatest solidifier of a nationality, and it is hardly credible that Southerners would have fought to such an extremity for independence if they had not been conscious of being a separate people.

C. Vann Woodward, Pulitzer Prize historian of Yale University in his famous study The Burden of Southern History (Louisiana State University Press, 1960), has emphasized this distinctive experience as giving Southerners a heritage of defeat and sorrow. Coupled with longstanding guilt and frustration from the difficulty of race relations, this burden of history has made Southerners a sadder, less optimistic, but perhaps wise and more realistic people than other Americans whose history has been one of uninterrupted success.

Woodward points also to another consequence of the War. In contrast to America in general, which has been a land of opportunity, progress, and prosperity, Southerners, both white and African-American, have a long experience of poverty. The most prosperous region of the United States in 1860, the South was from 1866 to at least World War II the most impoverished. An estimated 60 percent of the region’s capital was destroyed by the War, leaving it economically helpless and subject to exploitation of its resources and peoples as a colony of the United States. In 1860 nearly all white Southern families were independent landowners. In 1900, forty percent of white Southerners were tenants or sharecroppers. And 60 percent of African-American Southerners were in this position, though in absolute numbers there were more white sharecroppers than black. In the 1930s, President Franklin D. Roosevelt famously referred to the South as “the nation’s No. 1 Economic Problem,” and public discussions were full of references to the South’s colonial economic status.

The South has long been known as a source of cheap labor. As well as African-Americans, hundreds of thousands of white Southerners have moved to the North and West in the 20th century, as industrial labor. In the North and West they were treated as and understood themselves to be a distinct ethnic group, referred to negatively as “hillbillies” and “Okies.” Evidences of this can still be seen (like “Little Dixie” neighborhoods in Chicago and country music in Bakersfield, California). It is impossible to over-estimate the effects of generations of poverty within a prosperous country in forming a distinct Southern identity. Even in currently prosperous and growing areas of the South today, the better jobs are largely occupied by newcomers from other parts of the country and the blue-collar jobs by native Southerners.

Southern differences in manners, speech, recreations, religious beliefs, cuisine, and music are commonplace observations in everyday life in the United States. These differences do not have to be absolute. Scots and some Irish and Welsh speak English and are like Englishmen in various was, but they are still obviously distinct nationalities, as are the French-descended Canadians. Speech, religion, music, manners, and cuisine are the universal markers of ethnic distinction. The proof of distinctive Southern characteristics in these areas is easily established by the well-known negative (and sometimes positive) reactions that Southerners receive from other groups.

Contemporary markers distinguishing Southerners as a distinct group have been given systematic scientific study, in the works of John Shelton Reed, Kenan Professor of Sociology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, especially The Enduring South.

Besides differences in lesser matters such as names of children, places, and businesses, Reed demonstrates that public opinion surveys have consistently shown statistically significant differentiation from the American average, especially in three areas:

1) Southerners are the most consistent believers in basic orthodox Christianity as measured by their belief in the Bible, a future state of rewards and punishments, and the reality of Evil, as well as in their church attendance. They even outscore Roman Catholics in other parts of the country on these factors.

2) Southerners are more local and family oriented, less interested in distant events and celebrities than Americans in general.

3) Southerners, for better or worse, live by a different definition of the line between private and public. They are more conscious of giving and receiving offense and tend to deal with such things in person rather than call in public authorities. For instance, in the South murders most commonly occur between persons who are acquainted. In the North there are more commonly attacks by strangers.

Reed has also demonstrated through scientific attitude surveys that Northern and Southern students at the cosmopolitan University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill recognize themselves as having different thoughts, feelings, and behavior. The distinctions discovered by Reed are not absolute—there is some overlap—but they are statistically significant (as well as readily confirmed by empirical observation). See the article by Reed from the Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups.

Another relevant work is The South and the Sectional Conflict by David M. Potter of Stanford University, generally recognized as one of the outstanding historians in the United States in the 20th century (Louisiana State University Press, 1968). Potter affirms the separateness of the Southern people and describes how that difference has been created by distinct folkways (thinking, feeling, behaving in ways common to members of the same social group) and separate political experiences.

The hallmarks of a living national culture are its production of arts both at the folk level (arising spontaneously from the people) and at the level of high culture. Southerners have produced several original styles of music and it is hardly to be doubted that Southern writers have produced a distinct (and highly regarded by the world) literature. The acclaimed novelist George Garrett has demonstrated that distinctive Southernness persists in the most recent generation of outstanding writers. And he has interestingly related Southern literary prowess to the distinctive manners of the region. George Garrett, “Southern Literature Here and Now,” in Fifteen Southerners, Why the South Will Survive (Athens and London: University of Georgia Press, 1981).

The history of a distinctive Southern speech has been examined by the world famous literary scholar and critic Cleanth Brooks (Yale University) in The Language of the American South (University of Georgia Press, 1985). Brooks has demonstrated how distinctive Southern speech has contributed to the success of Southern literary efforts. The distinctiveness of Southern accents was part of the lifelong study of the greatest American scholar of English dialects, Raven I. McDavid of the University of Chicago, author of Linguistic Atlas of the Middle and South Atlantic States (Chicago, 1980 and later editions) and Sociolinguistics and Historical Linguistics (University of Odense, Denmark).

That Southerners can be distinguished by differing voting behavior is a commonplace calculation of politicians and news media and is the subject of much continuing study by political scientists.

Establishing the reality of the Southerner is akin to proving that Iowa grows corn or that Hollywood is located in California. When the term “Southern” is used, there is not a mind in America that does not immediately reference impressions, favorable or unfavorable, of particular history, literature, music, cuisine, manners, and political and religious tendencies.

I would like to conclude my expert testimony with a personal statement derived from a speech I made at the annual meeting of the Southern Historical Association in New Orleans in 1995, parts of which were published in the journal Southern Cultures (University of North Carolina). It refers not to the “Civil War” but to Southern identity today:

The Confederate Battle Flag: A Symbol of Southern Heritage and Identity

I remember my own father and uncles returning from World War II with stories of how Southerners, particularly rural and working class ones, were denigrated and ridiculed by urbanites for their speech, manners, and attitudes. There was a general cultural attack at the time on “hillbillies.” This was the beginning of my consciousness of belonging to a separate people from other Americans. It was at that time that we began to display the Confederate battle flag at times from the front porch and to observe Lee’s birthday and Confederate Memorial Day. It is relevant, too, that my grandmother was the daughter of a Confederate soldier and had a fund of stories of the family in the War. Our identification with the Confederate battle flag was nearly a decade before Brown vs. Board of Education and it had nothing to do with segregation, the Dixiecrat movement of 1948, or football, contrary to what has been stated by several scholars who have claimed to study the matter impartially.

My Southern identity had thus been brought to my attention before I entered school, and the battle flag was the obvious symbol of that identity, and a beautiful and hallowed object as well. Time, and the success of the civil rights movement and other great changes in the South, have done nothing to diminish this. Rather, to the contrary. The fact that the United States is increasingly a multicultural empire rather than a federal republic, will make ethnic identities, including the Southern, even sharper in the future, which bodes well to see symbolic struggles among Northerners, Latin Americans, African-Americans and Asians. Southerners, the oldest and largest minority in America, have a right to claim their heritage and its symbols. The South is larger in territory, population, economic strength, and history and more distinct in culture than many of the separate nations of the earth.

In recent years, I have spoken often to meetings of the Sons of Confederate Veterans, the United Daughters of the Confederacy, Civil War Roundtables, local historical societies, and other groups. These groups of good citizens are full of defenders and displayers of the battle flag. For most of these good Americans the flag is not a symbol of white supremacy, but an identification with their own ancestors and heritage and an affirmation of then own identity.