This piece is published in honor of Davis’s birthday, June 3.

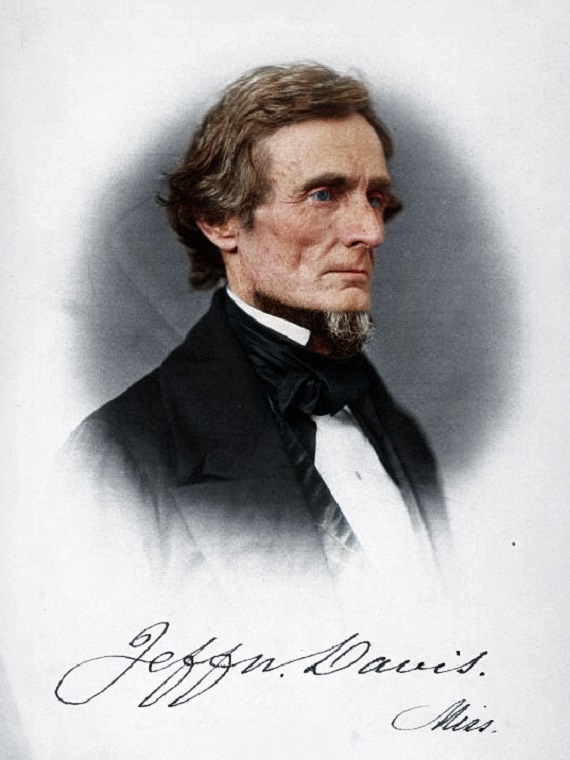

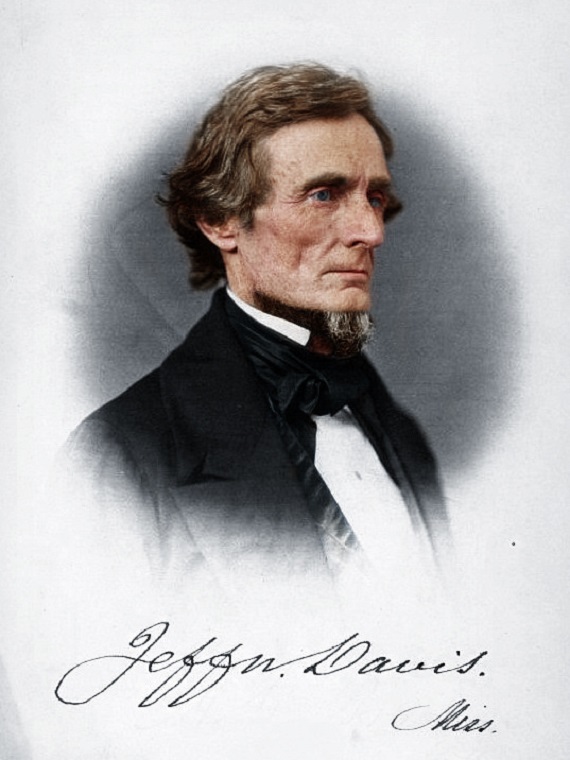

With unaffected distrust of my ability to meet the demands of such a great hour as this, I rejoice to be again on the beautiful campus of my alma mater, and have the opportunity of bringing a message to the young men of my country. And as this commencement day chances to be the one-hundredth anniversary of the birth of Jefferson Davis, the most illustrious citizen whose name ever adorned and enriched the annals of Mississippi, I have had the temerity to select his Life and Times as the theme of this hour’s discussion. To paint, with skillful hand, the full length portrait of that majestic man, or adequately portray the qualities that gave him greatness and the virtues that make him immortal, I cannot; but, with you, I can reverently sit at his feet and listen to a story that will stir within us many a noble aspiration, and cause us to seek more diligently the old paths of manly honor and high endeavor. My purpose is not to indulge in extravagant or indiscriminate eulogy, but, if possible, give a judicial estimate of a great man who was the most commanding figure in a fierce and eventful national crisis. It shall be alike removed from unreasoning censure and unreasonable praise. We need not deify Mr. Davis, or disproportionately exalt the pedestal on which the Genius of History will surely place him, in order to show adequate appreciation of his noble character and splendid genius. On the other hand, the use of bitter invective and lurid superlatives about this man of destiny, may evidence literary ingenuity and partisan malignity, but can never any more command the respect of patriotic, thoughtful students of our national history. The days of malignant vituperation are gone, and the time of judicial interpretation has come. It is not necessary now to “measure all facts by considerations of latitude and longitude.” The character and life work of Jefferson Davis were never so diligently and dispassionately studied as to-day. War-passions have sufficiently cooled, and war-clouds have so floated forth our national skies that even the most ardent and sentimental nationalist can study the man and his times in a clear, white light. A citizen whose moral and religious ideals were the most exalted, and whose daily conduct was sought to be modeled after the Man of Galilee, and whose life has in it as little to explain or apologize for, as any leader in American politics, can never be caricatured as a monster or condemned as a traitor, and have anybody really believe it.

The unanswered question in England for two hundred and forty years was, “Shall Cromwell have a statue?” It required nearly two and a half centuries for public opinion to reach a just estimate of the most colossal figure in English history. The great Lord Protector died at Whitehall and was laid to rest, with royal honors, in Westminster Abbey. But when the monarchy was restored, and Charles II ascended the throne, his body was disinterred, gibbetted at Tyburn Hill and buried under the gallows, the head being placed on Westminster Hall. Now, a magnificent statue of the great Oliver stands opposite where his head was exposed to the jeers of every passer-by — England’s sane and final estimate of the mightiest man who ever led her legions to victory or guided the course of her civil history. “In the new world, events move faster, popular passion cools quicker, and calm judgment more speedily reascends its sacred throne. After forty years since the Civil War, the nation’s estimate of Jefferson Davis— the Oliver Cromwell of our Constitutional crisis—has almost entirely changed, and points to the not far-off day when no place in our Federal capital will be too conspicuous for his heroic statue. Mr. Davis can no more be understood by reading the heated columns of the political newspapers and historical writers of the days immediately succeeding the Civil War than Oliver Cromwell could be judicially interpreted by the obsequious literature of the reign of Charles II.

Mr. Davis had his limitations, and was not without his measure of human faults and frailties: but he also had extraordinary gifts and radiant virtues and a brilliant genius that rank him among the mightiest men of the centuries. .He made mistakes, because he was mortal, and he excited antagonisms because his convictions were stronger than his tactful graces; but no one who knew him, and no dispassionate student of his history, ever doubted the sincerity of his great soul or the absolute integrity of his imperial purpose. Let us, on his anniversary day, learn some patriotic lessons from the life-history of this greatest Mississippian, replight our faith to the unalterable principles of Constitutional liberty to which he was passionately devoted, and renew our fealty to the flag of our reunited country, which he never ceased to love.

I have read of a peculiar notion entertained by the ancient Norsemen. They supposed that, beside the soul of the dead, a ghost survived, haunting for awhile the scenes of his earthly labors. Though at first vivid and life-like, it slowly waned and faded, until at length it vanished, leaving behind no trace or memory of its spectral presence. I am glad that the ghosts of old sectional issues are vanishing and soon will cease to haunt and mock the fears of the most anxious and nervous of American patriots. It is a grateful fact, in which all rejoice, that this nation is more united in heart and purpose to-day than ever in its history.

While I would not needlessly stir the embers of settled strife or reopen the grave of buried issues or, by a word, revive the bitter memories of a stormy past, it is due the truth of history that the fundamental principles for which our fathers contended should be often reiterated, in order that the purpose which inspired them may be correctly estimated and the purity of their motives be abundantly vindicated.

If the condition of affairs in 1860 be thoroughly understood, and one has a clear and accurate knowledge of the nature and character of the Federal Government, together with the rights of the States under the Constitution, we need not fear the judgments that may be formed and the conclusions that will be reached. But unfortunately for the truth of history, up to recent years, we have been “confronted by dogmas which are substituted for principles, by preconceived opinions which are claimed to be historical verities, and by sentimentality which closes the avenues of the mind against logic and demonstration.”

But before studying the lessons of a great cause, a great leader, and a great era, I call attention to a rather singular historic fact. The most illogical and unreasoning sentiment—which yet lingers, but is fast fading— a sentiment universal in the North and more or less entertained in the South—is that which has persistently discriminated against Mr. Davis, holding him to vindictive account for the ever-to-be lamented war and all its terrible consequences, while others have been acquitted of blame, and many applauded as patriots and heroes. Upon his weary shoulders have been piled the sins of the South, and he has been execrated as the arch-traitor of American politics. Those who thus judge have taken counsel of their prejudices, and evidence an almost criminal ignorance of the facts of history. Was Mr. Davis more a sinner than Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson, that he should be condemned and they so universally praised? Did he follow any flag,for which they did not draw their swords? Did he advocate any doctrine to which they did not subscribe, and write their names in blood? Did he avow allegiance to any government to which they did not pledge life and sacred honor? And yet, in some sections of our country, he has been gibbetted, and they have been applauded.

I know there is a certain glamour that gathers about a military hero which commands admiration and calls for extravagant laudation. One who braves the shout of battle and wins the chaplet of victory, is unconsciously invested with a halo more brilliant than the crown of any civilian, however marvelous his gifts or magnificent his achievements or immortal the results of his public labors. People will applaud the returning conqueror while they forget the founder of an Empire or the author of a nation’s Constitution. By virtue of his exalted position, first as the trusted political leader of a great party, and then as the President of a stormcradled nation, Mr. Davis invited antagonisms and could not escape the sharpest criticism. Having to deal with the rivalries of political leaders, the jealousies of military aspirants, the bitterness of the disappointed, the selfishness of the discontented, and indeed all classes, in every department of the civil and military service, he had to hear every lament and patiently bear every complaint. In the North, he was charged with everything, from the sin of secession to the “horrors of Andersonville” and the assassination of Mr. Lincoln. In the South he was held accountable for everything, from the failure to capture Washington after the first battle of Manassas to the unsuccessful return of the Peace Commission and the surrender of Lee’s tattered legions at Appomattox.

As this discussion will be more the study of an epochal man and his times, rather than the recital of personal history, I shall not repeat in detail the well known facts of an eventful career. The son of a gallant Revolutionary soldier, and with the finest strain of Welch blood flowing in his generous veins, Jefferson Davis was born in the State of Kentucky. In infancy he was brought by his father to Mississippi, and here his entire life was spent. At the county school he was prepared for Transylvania College, from which, at the age of sixteen, he passed to the United States Military Academy at West Point. In that institution he was distinguished as a student and a gentleman, and in due time was graduated with high honor.

Jefferson Davis began life well. He had a clean boyhood, with no tendency to vice or immorality. That was the universal testimony of neighbors, teachers and fellow-students. He grew up a stranger to deceit and a lover of the truth. He formed no evil habits that he had to correct,—and forged upon himself no chains that he had to break. His nature was as transparent as the light that shone about him; his heart was as open as the soft skies that bent in benediction over his country home; and his temper as sweet and cheery as the limpid stream that made music in its flow through the neighboring fields and forests.

Graduating from West Point in 1828, he was commissioned a Second Lieutenant in the regular army, and spent seven laborious years in the military service, chiefly in the middle Northwest, and had some conspicuous part in the Black Hawk War. In 1835 Lieutenant Davis resigned from the regular army, married the charming daughter of General Zachary Taylor, and settled on his Mississippi plantation, to follow the luxurious, literary life of a cultured, Southern gentleman. But the untimely death, in a few short months, of his fair young bride, crushed his radiant hopes and disappointed all his life-plans. After seven years, spent mostly in agricultural pursuits, and in literary study, especially the study of political philosophy and constitutional history, he entered public life, and almost immediately rose to trusted and conspicuous leadership.

In 1844 Mr. Davis was elected to Congress, and ever thereafter, up to the fall of the Confederate Government, was in some distinguished capacity or other connected with the public service of his country. When he entered the halls of Congress, the “Oregon question,” the reannexation of Texas, and the revision of the tariff were the stormy issues that divided the nation into two hostile camps. The scholarly young representative from Mississippi soon appeared in the lists, and by his thorough mastery of the questions involved attracted national attention. The venerable ex-President, John Quincy Adams, the “old man eloquent,” at that time a member of the House, was greatly impressed with his extraordinary ability and predicted his brilliant parliamentary career. Referring to his first set speech in Congress, a recent biographer, makes this just and suggestive observation: “He manifests here, in his early efforts as a legislator, some of the larger views of national life and development which have been so persistently ignored by those who have chronicled his career.”

In that first great speech, which had all the marks and carried all the credentials of the profoundest statesmanship, Mr. Davis made this broad declaration from the principle of which he never receded: “The extent of our Union has never been to me the cause of apprehension: its cohesion can only be disturbed by violation of the compact which cements it.”

Believing, as he did, in the righteousness of the conflict with Mexico, Mr. Davis earnestly advocated the most liberal supply of means and men to prosecute the war, and announced himself as ready, should his services be needed, to take his place in the tented field. In June, 1846, a regiment of Mississippi volunteers was organized at Vicksburg, and Jefferson Davis was elected its colonel. He accordingly resigned his seat in Congress, hastened to join his regiment, which he overtook at New Orleans, and reported for duty to General Taylor on the Mexican border. At Monterey and Buena Vista, crucial positions of the war, his command rendered conspicuously heroic service. Our American knighthood was in fairest flower that day, especially on the plains of Buena Vista, when Colonel Davis, against overwhelming numbers, snatched victory from almost certain defeat, and won immortal fame for himself and his gallant Mississippi Rifles. By a brilliant tactical movement he broke the strength of the Mexican army and sent General Santa Anna southward with only half the force of the day before. Though severely wounded, he remained in his saddle, refusing to quit the field, until the day of glorious triumph was complete. General Zachary Taylor, Commander-in-Chief of the American forces, paid this eloquent tribute to the soldierly courage and genius of the distinguished Mississippian: “Napoleon never had a Marshal who behaved more superbly than did Colonel Davis to-day.”

Returning from Mexico, having won the highest honors of war, Colonel Davis and the brave remnant of his magnificent regiment, were everywhere welcomed with boundless enthusiasm. He was tendered the position of Brigadier-General of Volunteers by President Polk, but declined, on constitutional grounds, holding that such appointment inhered only in the State.

Within two months after his return from Mexico, crowned with immortal honor, Mr. Davis was appointed by the Governor to represent Mississippi in the United States Senate, a vacancy having occurred by the death of Senator Spaight. When the Legislature met he was elected unanimously for the remainder of the unexpired term, all party lines having disappeared in a. universal desire to honor the brilliant young Colonel of the Mississippi Rifles. That was a position most congenial to his tastes and ambitions, and there his superb abilities shone with a splendor rarely equaled in the parliamentary history of America. He was an ideal Senator, dignified, self-mastered, serious, dispassionate, always bent on the great things that concerned the welfare of the nation. He was never flippant—never toyed with trifles—and never trifled with the destiny of his people. His was the skill and strength to bend the mighty bow of Ulysses.

When Jefferson Davis entered the United States Senate, the glory of that upper chamber was at its height. Possibly never at one time had so many illustrious men sat in the highest council of the nation. There were giants in those days. There sat John C. Calhoun, of South Carolina; Daniel Webster, of Massachusetts; Henry Clay, of Kentucky; Thomas H. Benton, of Missouri; Louis Cass, of Michigan; Salmon P. Chase, of Ohio; Stephen A. Douglass, of Illinois, and other men of lesser fame. In that company of giants Jefferson Davis of Mississippi at once took rank among the greatest, “eloquent among the most eloquent in debate,” and worthy to be the premier at any counciltable of American statesmen. The historian, Prescott, pronounced him “the most accomplished” member of the body.

One, who spoke by the authority of large experience with the upper chamber, thus correctly characterized our brilliant and accomplished young Senator: “It is but simple justice to say, that in ripe scholarship, wide and accurate information on all subjects coming before the body, native ability, readiness as a debater, true honor and stainless character, Jefferson Davis stood in the very first rank, and did as much to influence legislation and leave his mark on the Senate and the country as any other who served in his day.”

Senator Henry Wilson, of Massachusetts, afterwards spoke of him as “the clear-headed, practical, dominating Davis.”

That which pre-eminently signalized the public character and parliamentary career of Jefferson Davis was his sincere, unwavering devotion to the doctrine of State sovereignty, and all the practical questions that flowed therefrom. He held with unrelaxing grasp to the fundamental fact that the Union was composed of separate, independent, sovereign States, and that all Federal power was delegated, specifically limited, and clearly defined. The titanic struggles of his entire public life were over this one vital issue, with all that it logically involved for the weal or woe of his beloved country. The Articles of Confederation declared, in express terms, that “each State retains its sovereignty, freedom and independence, and every power, jurisdiction and right, which is not by this Confederation expressly delegated to the United States in Congress assembled,” and that principle was transferred intact to the Constitution itself. And as one function of sovereignty was the right to withdraw from a compact, if occasion demanded, he planted himself squarely upon that doctrine, and never wavered in its able and fearless advocacy;—a doctrine, by the way, that was never questioned by any jurist or statesman for forty years after the Constitution was adopted.

Having read and re-read, with great diligence and no less delight the whole history of the fierce controversies that culminated in the war between the States, including the ablest speeches of our profoundest statesmen on both sides, and with all my genuine pride in a restored Union, I am bound to say that the Southern position was never shaken, and that the overwhelming weight of argument was on the side of John C. Calhoun and Jefferson Davis. And further, it was by surrendering the Constitutional argument and resorting to what was denominated “the higher law” of political conduct and conscience that the North found apology or defence for its attitude toward the inalienable rights of the Southern States.

In order that you may appreciate the grounds of my confident assertion, I quote a few paragraphs from what seems to me an absolutely unanswerable argument by John C. Calhoun, the greatest logician and profoundest political philosopher in the nation: “In that character they formed the old Confederation, and when it was proposed to supersede the Articles of the Confederation by the present Constitution, they met in convention as States, acted and voted as States, and the Constitution, when formed, was submitted for ratification to the people of the several States. It was ratified by them as States, each State for itself; each, by its ratification, binding its own citizens: the parts thus separately binding themselves, and not the whole, the parts: and it is declared in the preamble of the Constitution to be ordained by the people of the United States, and in the Article of Ratification, when ratified, to be binding between the States so ratifying. The conclusion is inevitable that the Constitution is the work of the people of the States, considered as separate and independent political communities; that they are its authors—their power created it, their voice clothed it with authority: that the government formed is in reality their agent, and that the Union, of which the Constitution is the bond, is a Union of States and not of individuals.”

And it is an interesting and suggestive fact that the latest historians and writers on constitutional government sustain the fundamental contention of Southern statesmen.

The Hon. Henry Cabot Lodge, the accomplished scholar and distinguished Senator of Massachusetts, in his Life of Daniel Webster, makes this candid statement: “When the Constitution was adopted by the votes of the States at Philadelphia and accepted by votes of States in popular conventions, it was safe to say there was not a man in the country, from Washington to Hamilton on the one side, to George Clinton and George Mason on the other, who regarded the new system as anything but an experiment entered upon by the States, and from which each and every State had the right to peacefully withdraw—a right that was very likely to be exercised.”

And in a recent illuminating address, the Hon. Charles Francis Adams, abundantly and absolutely vindicates the contention of Mr. Davis and other Southern leaders, in this noble utterance: “To which side did the weight of argument incline during the great debate which culminated in our Civil War? The answer necessarily turns on the abstract right of what we term a sovereign State to secede from the Union at such time and for such cause as may seem to that State proper and sufficient. The issue is settled; irrevocably and for all time decided; it was settled forty years ago, and the settlement since reached has been the result not of reason based on historical evidence, but of events and of force.” And Mr. Adams further added: “The principles enunciated by South Carolina on the 20th of December, i860, were enunciated by the Kentucky resolutions, November 16, 1798.”

The position of Jefferson Davis, though by his enemies often denied and persistently obscured, was this—that while consistently and unanswerably defending the right of a State to secede, he never urged it as a policy, and deplored it as a possible necessity. Or to use the language of the resolution adopted by the States Rights Convention of Mississippi in June, 1851, drawn by his own hand, “Secession was the last alternative, the final remedy, and should not be resorted to under existing circumstances.”

It may be interesting, in this connection, to inquire when the exercise of a State’s right to secede had its first and most threatening assertion. Alexander H. Stevens affirms that the right of a State to withdraw from the Union was never denied or questioned by any jurist, publicist or statesman of character and standing “until Kent’s Commentaries appeared in 1826, nearly forty years after the Government had gone into operation.” And it is historic truth to state, that the first threat to exercise this right, universally recognized in the early days of the Republic, was not heard in the South—”it first sprang up in the North.” Not only so, but from 1795 to 1815, and again in 1845, there was an influential party in New England who favored and threatened the formation of a Northern Confederacy. Roger Griswold, a representative in Congress from the State of Connecticut, in 1804, declared that he was in favor of the New England States forming a republic by themselves and seceding from the Union. Joseph Story, when in Congress, afterwards a Justice of the Supreme Court and Commentator on the Constitution, said: “It was a prevalent opinion then in Massachusetts * * * of a separation of the Eastern States from the Union.”

In a famous speech delivered by Josiah Quincy, in Congress, January 14, 1811, against the admission of Louisiana into the Union as a State, these sentiments were defiantly uttered: “I am compelled to declare it as my deliberate opinion that if this bill passes, the bonds of this Union are virtually dissolved: that the States which compose it are free from their moral obligations, and that, as it will be the right of all, so it will be the duty of some, to prepare definitely for a separation, amicably, if they can, violently if they must.” It must not be forgotten that these are not the words of Jefferson Davis. When he defended the doctrine of a State’s right to sever its relation with the Union, he was denounced as a conspirator against the life of the nation.

On December 15, 1814, the Hartford Convention assembled, composed of delegates from all the New England States, to protest against the war then in progress between the United States and England. They had suffered immense loss by the destruction of their commerce and fisheries, and rather than endure more for the Nation’s account, they preferred to withdraw from the Union. The report, adopted unanimously by the convention, contains this language: “In case of deliberate, dangerous and palpable infractions of the Constitution, affecting the sovereignty of a State, and the liberties of the people, it is not only the right, but the duty of such a State to interpose its authority for their protection, in the manner best calculated to secure that end. When emergencies occur, which are either beyond the reach of judicial tribunals, or too pressing to admit of the delay incident to their forms, States which have no common umpire, must be their own judges and execute their own decisions.”

While that threat was never carried into execution— the treaty of Ghent having been signed in the meantime —there is the solemn assertion on the part of these New England delegates, of their sovereign right to withdraw from the Union, if occasion seemed to demand. I make no comment upon the fact that while New England was meditating withdrawal from the Federal compact, General Andrew Jackson and his heroic legions in the battle at New Orleans, were shedding their blood for the honor of our national flag. But I venture to ask this question, is there anything in the lapse of a few years to make the utterances of Roger Griswold and Rufus King and Joseph Story and Josiah Quincy and the Hartford Convention less disloyal than the calm, philosophic reasoning of John C. Calhoun and Jefferson Davis? And yet no one ever hears of New England as “the hot bed of secession,” and her political leaders as conspirators against the life of the Nation. No fair-minded student of history can acquit Josiah Quincy and find fault with Jefferson Davis.

The Legislature of Massachusetts, in 1809, declared the embargo law “not legally binding on the citizens of the State.” Now in New England that was simply the assertion of inalienable rights! If in South Carolina, it would have been, and was, denounced as the vilest nullification.

Now I come to the conditions and questions that immediately preceded, if they did not precipitate, the dismemberment of the Union. Slavery, which existed in all but one of the States when the Union was formed, and in fifteen of them when the war began, was the occasion, but not the cause of the lamented conflict. But as Mr. Davis well said, “In the later controversies, * * *, its effect in operating as a lever upon the passions, prejudices or sympathies of mankind, was so potent that it has been spread like a thick cloud over the whole horizon of historic truth.”

The right or wrong of slavery we need not discuss, or attempt to determine who was most responsible therefor. The institution is dead beyond the possibility of resurrection, and the whole nation is glad. The later geographical limitations of slavery in the United States were determined, not by conscience, but by climate. It was climate at the North and the cotton gin in the South that regulated the distribution of slave labor. I have scant respect for a conscience too sensitive to own certain property because it is immoral, but without compunction will sell the same to another at full market value. Had the slave-holders of the North manumitted their slaves— and not sold them because their labor ceased to be profitable, there would have been more regard for their subsequent abolition zeal. It is a matter of pride with us, that no Southern colony or State ever had a vessel engaged in the slave trade. And several of the Southern States were the first to pass stringent laws against the importation of African slaves.

But apart from the ethical question involved, as we now see it, slave property was recognized by the Constitution and existed in every State but one when the Union was formed. And a clear mandate of the Constitution required slaves to be delivered up to their owners when escaping into another State. Congress passed laws to enforce the same, and their constitutionality was sustained by the Supreme Court in the famous Dred-Scott decision. Daniel Webster, too great to be provincial, and too broad to be a narrow partisan, in a noble speech at Capon Springs, Va., in 1851, made this emphatic declaration:

“I have not hesitated to say, and I repeat, that it_the Northern States refuse, wilfully and deliberately, to carry into effect that part of the Constitution which respects the restoration of fugitive slaves, and Congress provide no remedy, the South would no longer be bound to observe the compact. A bargain cannot be broken on one side and still bind the other side. I say to you, gentlemen in Virginia, as I said on the shores of Lake Erie and in the city of Boston, as I may say again, that you of the South have as much right to receive your fugitive slaves as the North has to any of its rights and privileges of navigation and commerce.”

And yet Charles Sumner, speaking for a great party growing in strength and dominance, with the rising sun of every day, said the North could not and would not obey the law. Wm. H. Seward declared that there was “a higher law” than the Constitution which would be the rule of their political conduct.

Now the insistence of Mr. Davis and his compatriots was that the Constitution and laws should be obeyed: that the individual, sovereign States must regulate their own domestic affairs without Federal interference, and that their property, of whatever kind, must be respected and protected. They resisted any invasion of the State’s right to control its own internal affairs as a violation of the sacred Federal compact. Over that one fundamental question an “irrepressible conflict” was waged for many stormy years. The advocates of State sovereignty were charged with disloyalty to the Union, while the Federalists were denounced as enemies of the Constitution and usurpers of the rights of the States.

And, by the way, our present day political discussions are eloquently vindicating the patriotic jealousy of Mr. Davis for the rights of the States. The most significant fact of these strenuous times is the solemn warnings, in endless iteration and from both political parties, against the ominous encroachments of Federal authority. More and more the nation is seeing that Jefferson Davis was not an alarmist or an academical theorist, but a practical, sagacious, far-seeing statesman, when he contended so persistently for the rights and unconstrained functions of each member of the Federal Union.

Sectional agitation and alienation continued, with slight interruption and increasing violence, for many weary years. Every lover of the Union deplored it, and every patriotic American sought some common ground on which all could stand, and the rights of each be preserved. But with every Congressional debate and political convention and Supreme Court decision, this animosity was kindled into fiercer flame. On both sides the bitterness was intense. Political differences ripened into personal hates and hostilities. Encounters between congressmen over sectional issues were a daily dread in Washington. One Senator said: “I believe every man in both houses is armed with a revolver.” Fourteen of the Northern States passed so-called “Personal Liberty Laws,” designed to nullify the Constitution, and encourage the people to disregard the Dred-Scott decision of the Supreme Court. State officers were prohibited from assisting in the arrest of fugitive slaves, while State’s attorneys were required to defend them, and provision made for paying the fugitive’s expenses out of the State treasury. Charles Sumner openly declared that the North would not obey the fugitive-slave laws. Wm, H. Seward, it was said, contributed money to John Brown which was used for pillage and murder. John Brown’s midnight raid on Harper’s Ferry was applauded to the echo throughout the North. And when the old assassin was executed, according to law, bells were tolled in many places, cannon were fired and prayers offered for him as if he were the saintliest of martyrs. By fervid orators he was placed on the same canonized roll with Paul and Silas.

On the other hand the South was equally intolerant and aflame with intense excitement. Commericial conventions in Charleston, Montgomery, Memphis and elsewhere adopted retaliatory measures against the aggressions of the North. Southerners declared that nonintercourse in business was “the one prescription for Northern fanaticism and political villiany.” Southern parents were condemned for patronizing Northern colleges, and urged to enlarge and equip their own institutions and to use only Southern text-books. “If our schools are not good enough,” they said, “let them be improved by a more hearty support: if this is not enough, let them patronize the universities of Europe rather than aid and abet in any way the bitter enemies of the Southland.”

And as further evidence that Northern leaders had determined no longer to uphold the Constitution and give to the South what she considered her rights and equality in the Union, we have only to reread the extreme and inflamed utterances of their chief men. What could the nation hope for when men in authority declared that the Constitution under which we lived is no longer of binding force, and that there is a “higher law” for the guidance of a citizen’s conduct and conscience? Wm. H. Seward, the acknowledged head of the Republican party, and the author of that doctrine, uttered these words: “There is a higher law than the Constitution which regulates our authority over the domain. Slavery must be abolished, and we must do it.”

Horace Greeley, a most potential voice in the councils of his party, did not hesitate to say: “I have no doubt but the free and slave States ought to be separated— The Union is not worth supporting in connection with the South.”

William Lloyd Garrison, at first derided as a fanatic, but afterwards followed as the voice of an apostle, thus advocated the cause of disunion:: “The union is a lie. The American union is an imposture, a covenant with death and an agreement with hell. We are for its overthrow! Up with the flag of disunion, that we may have a free and glorious republic of our own.”

Wendell Phillips, the most eloquent, orator in New England, and whose leadership was commanding, fed the flames of sectional animosity with speeches such as this: “There is merit in the Republican party. It is this:—it is the first sectional party ever organized in this country—It is not national; it is sectional. It is the North against the South—The first crack in the iceberg is visible: you will yet hear it go with a crack through the center.”

The New York Tribune, for many years the acknowledged and most influential organ of Republican opinion in the United States, thus bade the South a respectful adieu: “The time is fast approaching when the cry will become too overpowering to resist. Rather than tolerate national slavery as it now exists, let the Union be dissolved at once.”

With such utterances, and the applauding echoes of a party flushed with political victory, ringing in their ears, the South had little occasion to hope for aggressions to cease and conditions to improve. But through all the years this storm was fiercely raging, the cool, sagacious Jefferson Davis never lost the clearness of his vision or allowed himself to be swept from his political moorings. He fought with all his superb skill and herculean strength for the rights of the States, and warned his opponents that continued Federal invasion might drive them from the Union, but at the same time he reiterated his undying love for the whole country and its organic law, and prayed that the day of disunion would never dawn.

In an eloquent speech, delivered at Portland, Maine, in 1858, Mr. Davis strikingly demonstrated the fact that State pride and devotion to State integrity strengthened, rather than weakened our attachment to the Federal Union; that the larger love we have for our national flag is fed by the passionate devotion we manifest in the welfare of an individual State. He said: “No one more than myself recognizes the binding force of the allegiance which the citizen owes to the State of his citizenship, but the State being a party to our compact, a member of the Union, fealty to the Federal Constitution is not in opposition to, but flows from the allegiance due to one of the United States. Washington was not less a Virginian when he commanded at Boston, nor did Gates and Green weaken the bonds which bound them to their several States by their campaigns in the South. In proportion as a citizen loves his own State, will he strive to honor her by preserving her name and her fame free from the tarnish of having failed to observe her obligations and to fulfill her duties to her sister States—Do not our whole people, interior and seaboard, North, South, East and West, alike feel proud of the Yankee sailor, who has borne our flag as far as the ocean bears its foam, and caused the name and character of the United States to be known and respected where there is wealth enough to woo commerce, and intelligence to honor merit? So long as we preserve and appreciate the achievements of Jefferson and Adams, of Franklin and Madison, of Hamilton, of Hancock, and of Rutledge,—men who labored for the whole country and lived for mankind,—we cannot sink to the petty strife which saps the foundations and destroys the political fabric our fathers erected and bequeathed as an inheritance to our posterity forever.”

And a few weeks thereafter, when on a visit to Boston, addressing a great audience in Faneuil Hall, and speaking not only for himself but for the entire South as well, he uttered sentiments as broadly and loyally national as were ever spoken by Thomas Jefferson or sung in the battle hymns of the republic. “As we have shared in the toils,” said he, “so we have gloried in the triumphs of our country. In our hearts, as in our history, are mingled the names of Concord, and Camden, and Saratoga, and Lexington, and Plattsburg, and Chippewa, and Erie, and Moultrie, and New Orleans, and Yorktown, and Bunker Hill. Grouped all together, they form a record of the triumphs of our cause, a monument of the common glory of our Union. What Southern man would wish it less by one of the Northern names of which it is composed? Or where is he, who gazing on the obelisk that rises from the ground made sacred by the blood of Warren, would feel his patriot’s pride suppressed by local jealousy?”

As late as December 20, 1860, after the presidential election and when events were hastening to a crisis, on the floor of the United States Senate, Mr. Davis reannounced his passionate love for the Union and pathetically plead for a spirit of conciliation that would make unnecessary the withdrawal of the South from their national fraternity. He said: “The Union is dear to me as a union of fraternal States. It would lose its value if I had to regard it as a union held together by physical force. I would be happy to know that every State now felt that fraternity which made this Union possible, and, if that evidence could go out, if evidence satisfactory to the people of the South could be given that that feeling existed in the hearts of the Northern people, you might burn your statute books and we would cling to the Union still.”

Instead of conspiring to disrupt the Union, as has been charged, Mr. Davis loved this great republic with passionate ardor and sealed that devotion with his richest blood. He served his country with a conscientious fidelity that knew no flagging. He went out at last in obedience to what he felt was imperative necessity, and the going almost broke his great heart. So reluctant was he to sever relations with the Union that some more ardent friends became impatient with his hesitation and almost suspected his loyalty. Despairing of any fair and final adjustment of issues that had agitated the nation for more than a half century, and believing that the election of Mr. Lincoln would embolden his party to great aggressions upon the constitutional rights of the Southern States, he, at length, with many a heartache, yielded to the inevitable and joined his people in the establishment of a separate civil government.

On January 20th, in a letter to his special friend, ex-President Franklin Pierce, he thus expressed the grief of his patriotic heart: “I have often and sadly turned my thoughts to you during the troublous times through which we have been passing, and now I come to the hard task of announcing to you that the hour is at hand which closes my connection with the United States, for the independence and union of which my father bled, and in the service of which I have sought to emulate the example he set for my guidance.”

As Mr. Blaine justly said of L. Q. C. Lamar, so will history say of Jefferson Davis: “He stood firmly by his State in accordance with the political creed in which he was reared; but looked back with tender regret to the union whose destiny he had wished to share, and under the protection of whose broader nationality he had hoped to live and die.”

And so consistent was his entire public career, and so conspicuous the unstained purity of his motives, that when nearing the close of his eventful life, he could challenge the world and triumphantly say: “The history of my public life bears evidence that I did all in my power to prevent the war; that I did nothing to precipitate collision; that I did not seek the post of chief executive, but advised my friends that I preferred not to fill it.”

Long after Yancey and Rhett and Toombs and others had thrown hesitancy to the winds, Mr. Davis still wrought with all his great ability and influence to preserve the Union. He favored and earnestly advocated the “Crittenden Resolutions” on condition that the Republican members accept them. Had they not stubbornly refused, and they did it on the advice of Mr. Lincoln, war would have been averted and the dissolution of the Union prevented, or postponed. All the undoubted facts go to prove that Jefferson Davis, at the peril of sacrificing the confidence of his people, exhausted all resources consistent with sacred honor and the rights of the States, to stay the fatal dismemberment of the Union.

Jefferson Davis’s farewell to the United States Senate, in which he had so long towered as a commanding figure, and where he had rendered his country such distinguished service, was one of the most dramatic and memorable scenes in the life of that historic chamber. Mississippi, by solemn ordinance, and in the exercise of her sovereign right, had severed her relation with the Union, and he, as her representative, must make official announcement of the fact, surrender his high commission, and return home to await the further orders of his devoted people. It was a supreme—a fateful hour— in our country’s history. The hush of death fell upon the chamber when Jefferson Davis arose. The trusted leader, and authoritative voice of the South, was about to speak, and an anxious nation was eager to hear. Every Senator was in his seat, members of the House stood in every available place, and the galleries were thronged with those whose faces expressed the alternating hopes and fears of their patriotic hearts. The fate of a nation seemed to hang upon that awful hour.

Pale, sad of countenance, weak in body from patriotic grief and loss of sleep, evidently under the strain of sacred, suppressed emotion, and yet with the calmness of fixed determination and settled conviction, the majestic Senator of Mississippi stood, hesitant for a moment, in painful silence. The natural melancholy in his face had a deeper tinge “as if the shadow of his country’s sorrow had been cast upon it.” His good wife, who witnessed the fateful scene, and felt the oppressive burden that almost crushed the brave heart of her great husband, said that “Had he been bending over his bleeding father, needlessly slain by his countrymen, he could not have been more pathetic and inconsolable.” At first there was a slight tremor in his speech, but as he proceeded his voice recovered its full, flutelike tones, and rang through the Chamber with its old-time clearness and confident strength. But there was in it no note of defiance, and he spoke no word of bitterness or reproach. He was listened to in profound silence. Hearts were too sad for words and hands too heavy for applause. Many eyes, unused to weeping, were dimmed with tears. And when he closed with these solemn words, there was a sense of unutterable sorrow in the entire assembly: “Mr. President and Senators, having made the announcement which the occasion seemed to me to require, it only remains for me to bid you a final adieu.” Senators moved softly out of the chamber, as though they were turning away from a new-made grave in which were laid their dearest hopes. Mrs. Davis says that the night after this memorable day brought no sleep to his eyelids, and all through its restless hours she could hear the oft-reiterated prayer: “May God have us in His holy keeping, and grant that before it is too late peaceful councils may prevail.”

In this open, manly, but painful way, the Southern States withdrew, with never a suggestion of conspiracy against anything or anybody. The men of the South wore no disguises, held no secret councils, concealed no plans, concocted no sinister schemes, organized no conclaves, and adopted no dark-lantern methods. They spoke out their honest convictions, made their pathetic pleas for justice, and openly announced their final, lamented purpose if all efforts at a peaceful adjustment should fail. And at length, whether wisely or unwisely, feeling that nothing else would avail, they determined to take the final step and fling defiance to the face of what they considered an aggressive, overbearing, tyrannous majority.

As Alexander H. Stephens admirably and correctly says, the real object of those who resorted to secession “was not to overthrow the government of the United States, but to perpetuate the principles upon which it was founded. The object in quitting the Union was not to destroy, but to save the principles of the Constitution.” And it is a significant fact, that the historic instrument, in almost its exact language, became the organic law of the Confederate Government. The Southern States withdrew from the Union for the very reason that induced them at first to enter into it; that is, for their own better protection and security.

Secession was not a war measure; it was intended to be a peace measure. It was a deeply regretted effort on the part of the South to flee from continued strife, feeling that “peace with two governments was better than a union of discordant States.” Hence Greely himself said: “If the Cotton States shall decide that they can do better out of the Union than in it, we insist on letting them go in peace.” And, while fearing the direful possibility, the Southern States seceded without the slightest preparation for war. As Dr. J. L. M. Curry said: “Not a gun, not an establishment for their manufacture or repair, nor a soldier, nor a vessel, had been provided as preparation for war, offensive or defensive. On the contrary, they desired to live in peace and friendship with their late confederates, and took all the necessary steps to secure that desired result. There was no appeal to the arbitrament of arms, nor any provocation to war. They desired and earnestly sought to make a fair and equitable settlement of common interests and disputed questions.” And the very first act of the Confederate Government was to appoint commissioners to Washington to make terms of peace, and establish relations of amity between the sections.

Some days after his farewell to the Senate Mr. Davis returned to his home in Mississippi to await results and render any service to which his country might call him. He did not, however, desire the leadership of the Confederacy that was in process of organization. But the people who knew his pre-eminent abilities and trusted his leadership declined to release him. By a unanimous and enthusiastic vote he was elected to the Presidency of the young republic, and felt compelled to accept responsibilities from which he hoped to escape. It was the thought of his countrymen, voiced by the eloquent Wm. L. Yancey, that “the man and the hour have met.” He could well say, therefore, in his inaugural address, delivered a few days after, that “It is joyous in the midst of perilous times to look around upon a people united in heart, when one purpose of high resolve animates and actuates the whole; when the sacrifices to be made are not weighed in the balance against honor and right and liberty and equality.” His address was conservative and dispassionate, but strong and resolute, not unequal to the luminous and lofty utterance of Thomas Jefferson. If others failed to measure the awful import of that epochal hour, not so the serious and far-seeing man about to assume high office, who was at once an educated and trained soldier and a great statesman of long experience and extraordinary genius.

To rehearse in detail the well known story of carnage and struggle is not within the purpose of this discussion. Nor is it necessary to consider at length the many and perplexing problems which signalized the administration of the young nation’s first and only President. It is sufficient to say that he conducted the affairs of the stormy government with consummate wisdom, meeting the sternest responsibilities, awed by no reverses, discouraged by no disaster, and cherishing an unshaken faith that a cause could not fail which was “sanctified by its justice and sustained by a virtuous people.” Even after Richmond was evacuated and the sun of Appomattox was about to go down amid blood and tears, a final appeal was issued in which he said: “Let us not despair, my countrymen, but meet the foe with fresh defiance and with unconquered and unconquerable hearts.”

Mr. Davis was a great President. In administering the affairs of the Confederate Government he displayed remarkable constructive and executive genius. Considering the resources at his command, all the Southern ports blockaded and without the recognition of any foreign nation, with no opportunity to sell cotton abroad and import supplies in return, having to rely entirely upon the fields and strong arms of the home land, and constantly menaced by one of the greatest armies of the world, it was remarkable that the young nation could have survived a few months, instead of four memorable years. And much of that wonderful history is due to its Chief Executive. In answer to one who sought General Lee’s estimate of Mr. Davis as the head of the government, he thus replied: “If my opinion is worth anything you can always say that few people could have done better than Mr. Davis. I know of none that could have done as well.”

And on the other side harsh criticism is giving way to generous and discriminating judgment. The Hon. Charles Francis Adams in a recent review of the latest “Life of Jefferson Davis” which has issued from the press, pays fitting tribute to the extraordinary ability displayed by the Confederacy’s great President: “No fatal mistake,” says he, “either of administration or strategy, was made which can fairly be laid to his account. * * * He did the best that was possible with the means that he had at command. Merely the opposing forces were too many and too strong for him. Of his austerity, earnestness and fidelity it seems to me there can be no more question than can be entertained of his capacity.”

Mr. Davis has been charged with cruelty to prisoners and on his shoulders have been laid the so-called “horrors of Andersonville,” a charge as utterly baseless as it is despicably mean. No more humane or gentle spirit ever walked this earth than Jefferson Davis. As a matter of fact there was no deliberate purpose on either side to maltreat prisoners of war, or fail to make proper provision for their care. The sufferings endured were only the exigencies of the awful days when great armies were in the death struggle for mastery. All that humanity could suggest and the meager resources of the South could provide were freely given for the brave men captured in battle. Mr. Davis said they were given exactly the same rations “in quantity and quality as those served out to our gallant soldiers in the field, which has been found sufficient to support them in their arduous campaigns.” On the contrary, goaded doubtless by false reports from the South, the United States War Department, on April 20, 1864, reduced by twenty per cent the rations issued to Confederate prisoners.

“With 60,000 more Federal prisoners in the South,” said Senator Daniel, “than there were Confederate prisoners in the North, four thousand more Confederates than Federals died in prison.” If those figures are correct the very repetition of the charge is an insult to intelligence and blasphemy against the truth. The real reason for so much suffering and mortality among the men in Southern prisons was that the Federal Government refused to observe the cartel agreed upon for the exchange of prisoners. And General Grant boldly assumed the responsibility for such refusal in these words: “It is hard on our men in Southern prisons not to exchange them, but it is humanity to those left in the ranks to fight our battles. If we commence a system of exchanges which liberates all prisoners taken, we will have to fight on until the whole South is exterminated. If we hold those caught they amount to no more than dead men. At this particular time to release all rebel prisoners North would insure Sherman’s defeat and compromise our own safety here.”

If any unfortunate prisoner was not comfortably provided for it was not because the South would be cruel to a brother, but on account of her exhausted source of supply. During the last year of the war General Lee had meat only twice a week, and his usual dinner was “a head of cabbage boiled in salt water, sweet potatoes and a pone of corn bread.” If the peerless Commander-in-Chief of the Confederate armies was reduced to such scanty fare, the government could not well provide very liberally for the gallant men in the ranks or behind prison doors.

Now, with this very imperfect sketch of a most remarkable career, I shall briefly refer to some of the qualities that made this heroic history a sublime possibility.

He was an accomplished orator and a magnificent debater. Having always complete mastery of himself and of the subject in hand, he became a veritable master of assemblies. He met Sargent S. Prentiss in debate, that inspired wizard of persuasive and powerful speech, and his friends had no occasion to regret the contest. Stephen A. Douglass found in him the mightiest champion with whom he ever shivered a lance. During an exciting discussion in 1850, Henry Clay turned to the Mississippi Senator and announced his purpose, at some future day, to debate with him a certain great question. “Now is the moment,” was the prompt reply of the brilliant Southern leader, whose intrepid courage and diligent student—habits kept him fully—armed for the issues of any hour.

“He was an archer regal

Who laid the mighty low,

But his arrows were fledged by the eagle

And sought not a fallen foe.”

One of Mr. Davis’s biographers, well acquainted with his parliamentary career, who knew his mastery in debate and his superb power as a statesman and an orator, and who witnessed his brilliant gladiatorial combat in the Senate with Stephen A. Douglass, gives this discriminating estimate of the great Mississippian:

“In nearly all of Mr. Davis’s speeches is recognized the pervasion of intellect, which is preserved even in his most impassioned passages. He goes to the very foundations of jurisprudence, illustrates by historical example, and throws upon his subject the full radiance of that light which is shed by diligent inquiry into the abstract truths of political and moral science. Strength, animation, energy without vehemence, classical elegance, and a luminous simplicity are features in Davis’s oratory which rendered him one of the most finished, logical and effective of contemporary parliamentary speakers. * * * He had less of the characteristics of Mirabeau than of that higher type of eloquence, of which Cicero, Burke, and George Canning were representatives, and which is’ pervaded by passion, subordinated to the severer tribunal of intellect”

His sensitiveness to personal and official honor, and his exceeding conscientiousness in the discharge of public duties were among the chief characteristics of this serious and stainless man. “Great politicians,” said Voltaire, “ought always to deceive the people.” But such was not the sacred creed of Jefferson Davis, who held that public men should invariably and scrupulously be honest with the people, having no confidences from which they are excluded and no policies in which they were not invited to share. Free from conscious sophistry and the very soul of candor, he never sought to conceal or obscure, but to make the truth so luminous that he who ran could read. His own eloquent characterization of President Franklin Pierce might be fittingly applied to Jefferson Davis himself: “If treachery had come near him it would have stood abashed in the presence of his truth, his manliness and his confiding simplicity.”

In official life he knew no word but duty. When in Congress a rivers and harbors bill was pending on one occasion, and seeing that combinations had been formed to secure certain local, trivial appropriations, he opposed the measure with characteristic vigor. In the course of the debate he was asked if he did not favor appropriations for Mississippi, in response to which he retorted sharply and concluded: “I feel, sir, that I am incapable of sectional distinctions upon such a subject. I abhor and reject all interested combinations.”

He was the very soul of chivalry. No plumed knight of the middle ages ever had higher regard for the virtue of woman or the integrity of man or the sacredness of a cause. Sensitive to wrong, cherishing above measure his stainless honor, he never in the least betrayed it nor allowed another to impugn it. Had he remained in the military service I doubt not that he would have been on the tented field what Sir Henry Havelock became to the chivalry of England.

His was a proud but a noble and affectionate nature. Some have thought him a cold, austere, severe man, lacking in the gentler elements and sympathies of a generous soul. But nothing could be further from the fact. His affections were most ardent, his friendships partook of the pathetic, and the tenderness of his heart often dimmed his eyes with tears. And he was at all times most approachable. No citizen was so poor, no soldier so humble, no man so obscure, as not to have ready access to his presence and sympathetic attention.

Mr. Davis was a statesman, with neither taste nor ability for mere political manipulation. He relied upon high argument, and not political management, to achieve the great ends for which his party stood, and for which this young republic was called into being. It was impossible for him to resort to questionable methods and demagogical appeal in order to win elections and carry out party or governmental policies.

He was a profound, philosophical statesman, with a thoroughly trained intellect and an exalted sense of moral responsibility. In his logical processes he quite resembled the illustrious John C. Calhoun, whose genius he greatly admired and with whose political creed he was in substantial accord. And when Mr. Calhoun passed away, amid the lamentations of the whole nation, the great party he had led with such consummate skill turned instinctively to Jefferson Davis as incomparably the ablest exponent of the basic principles for which they fearlessly stood. His superb and commanding leadership vindicated their generous confidence and vastly enlarged the strength and measure of his national influence.

As Secretary of War in the cabinet of Franklin Pierce, and by common consent he was the Premier in that body of statesmen, it is no disparagement of others to say that no abler or more accomplished Secretary ever sat at the council table of an American President.

Providence designed him for leadership and amply endowed him with gifts to meet its repeated exigencies and imperial responsibilities. And in every position to which he was summoned, the results of his labors and the splendor of his achievements gave eloquent attention to the prescience of his statesmanship and the grandeur of his character.! The verdict of history will be, notwithstanding the fall of the Confederate Government, that he was pre-eminently the man for a crisis. His genius was most resplendent when the clouds were darkest, and the tension was greatest and the danger was nearest. When passion swayed the hour he was in most perfect command of his highest powers, and seemed to exercise the coolest judgment. He was cautious without; timidity, intrepid without rashness, courteous with condescension, pious without pretence.

And no public man ever had more loyal support and a more enthusiastic following. The Tenth Legion of Caesar and the Old Guard of Napoleon never followed their leaders with more perfect assurance or. thrilling ardor than did the friends of the superb chieftain whose one-hundredth anniversary we celebrate to-day.

“Courage that could dare and do,

Steadfast faith and honesty,

Were the only craft he knew

And his sole diplomacy.”

Mr. Davis was a devout believer in the fundamental verities of our Christian faith, and sought to make them the inspiring rule of his daily life. He was acquainted with the Scriptures from a child, and knew the place and power of prayer. His unshaken faith gave him sublime courage for duty, a serene fortitude in calamity, softened the rigor of the cruel prison, and made radiant the evening skies of life’s long stormy day. His intimate friend, the eloquent Senator Benj. H. Hill, of Georgia, paid this heart tribute to the beauty and consistency of his Christian character:

“I know Jefferson Davis as I know few men. I have been near him in his public duties. I have seen him by his private fireside; I have witnessed his humble Christian devotions, and I challenge the judgment of history when I say no people were ever led through the fiery struggle for liberty by a nobler, truer patriot, while the carnage of war and the trials of public life never revealed a purer and more beautiful Christian character.”

When after their capture his friend, the Hon. John H. Reagan, the Postmaster General of the Confederacy, was separated from him to be sent to a Northern prison, while he remained at Fortress Monroe, Mr. Davis said: “My old friend read frequently the Twenty-sixth Psalm; it has often given me the surest consolation.” While enduring in agony and chains his imprisonment at Fortress Monroe, a cruelty that will ever be a blot upon our country’s fair fame, he wrote thus cheerfully to his anxious and devoted wife: “Tarry there the Lord’s leisure, be strong and He will comfort thy heart. Every day, twice or oftener, I repeat the prayer of St. Chrysostom.” Again, from the dungeon he wrote to a friend: “Separated from my friends of this world, my Heavenly Father has drawn nearer to me.”

And when his two pitiless years of imprisonment were ended, broken in health but unbroken in spirit, and when the short court proceedings were concluded in Richmond, which restored him to liberty and the bosom of his family, and a party of friends had joined Mrs. Davis at the hotel, the venerable Chief of the Lost Cause turned to his old pastor and said: “Mr. Minnegarode, you have been with me in my sufferings and comforted and strengthened me with your prayers; is it not right that we now once more should kneel together and return thanks?”

After his release, in shattered health and poverty, his fortune having gone with the cause he served and for which he suffered, but rich in the affectionate devotion of the people, who vied with each other in doing him honor, he returned to his beloved Mississippi and here spent the remnant of his heroic years. Out of fire and tempest and.baptism of blood he came with an unfaltering purpose and an unclouded sky. There is something strangely beautiful in the old age of a great and good man. No sun sweeping through the opening gates of the morning has ever the radiant glory of his calm setting. Beautiful and bouyant as is the springtime, it fades before the color and splendor of the autumn. And so, there is a sweet serenity and chastened beauty about the evening of a cheerful, well spent life that far exceeds the brightness and bloom of its fair young morning.

The last days of Jefferson Davis were peaceful and beautiful. They were spent in dignified retirement, cultivating the sweet companionship of books, enjoying the association of friends, and in writing a masterly exposition of the great principles of government that had been the creed of his political faith and the ground of his people’s hopes. This was his last will and testament to those “who have glorified a fallen cause by the simple manhood of their lives, the patient endurance of suffering and the heroism of death.”

Though never an indifferent observer of passing events, he wisely took no part in public affairs and rarely ever appeared on public occasions. When occasionally one of the numerous invitations with which he was overwhelmed was accepted, it was to speak words of encouragement and hope to his people, urging them, with stout hearts and strong hands, to labor for the largest good of our reunited country.

In a notable address before the Legislature of Mississippi in 1884, when in age and feebleness extreme, standing in the old hall where in the days of his splendid prime he swayed’ enraptured audiences as with the wand of a mighty magician, he thus spoke to the people who had ever held the highest place in his affectionate heart: “Reared on the soil of Mississippi, the ambition of my boyhood was to do something which would redound to the honor and welfare of the State. The weight of many years admonishes me that my day of actual services has passed, yet the desire remains undiminished to see the people of Mississippi prosperous and happy, and her fame not unlike the past, but gradually growing wider and brighter as the years roll away. * * * Fate decreed that we should be unsuccessful in the effort to maintain and resume the grants made to the Federal Government. Our people have accepted the decree; it therefore behooves them to promote the general welfare of the Union, to show to the world that hereafter, as heretofore, the patriotism of our people is not measured by lines of latitude and longitude, but is as broad as the obligations they have assumed and embraces the whole of our ocean-broad domain.”

And now, young men of our reunited country, sons of heroic sires, proud of the flag that floats over us, and jealous of its increasing and unfading glory, glad that there is a star on it that answers to the name of Mississippi, I commend to your emulation the words of solemn counsel and patriotic encouragement with which Mr. Davis concluded his masterly and monumental work, “The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government”: “In asserting the right of secession it has not been my wish to incite to its exercise. I recognize the fact that the war showed it to be impracticable, but this did not prove that it was wrong, and now, that it may not be again attempted, and the Union may promote the general welfare, it is needful that the truth, the whole truth, should be known, so that crimination and recrimination may forever cease,, and then, on the basis of fraternity and faithful regard for the rights of the States, there may be written on the arch of the Union, ‘Esto Perpetua.'”

By the sacred political convictions which had inspired his every public and patriotic service, he consistently lived to the end, and went down to his grave without laying any sacrifice of repentance upon the altar of his conscience or his country. Without compromise or modification, and with never a suggestion of contrition or concession, he died in the accepted faith of his fathers. And for that fearless and unshaken fidelity to his honest conception of truth and duty, the South will continue to adore him, the world will never cease to admire him, and with a wreath of unfading glory the genius of history will not fail to crown him. For the future he had no fear. In the last public paper that emanated from his pen, representing himself and his countrymen, he calmly reiterated his unfaltering faith in these words: “We do not fear the verdict of posterity on the purity of our motives or the sincerity of our belief, which our sacrifices and our career sufficiently attested.”

Had he ever recanted or even receded,—had he ever apostatised or even compromised,—had he shown in any way that his often reiterated doctrines were not the undying convictions of his sincere soul,—had he ever plead for pardon on the ground that he had misconceived the truth and misguided his people,—the South would have spurned him, the North would have execrated him, and the verdict of history would have deservedly and eternally condemned him. But, in the calm consciousness of having done what sacred duty and the cause of constitutional liberty seemed to demand, to the end of his days he walked with a steady step that knew no variableness or shadow of turning. The banner under which he fought went down in blood and tears, but was never furled by his hands.

And for us to be honestly and absolutely loyal to the whole country and our glorious flag, we need not and will not forget or cease to venerate the exalted character and splendid virtues and unsullied patriotism of Jefferson Davis and his compeers.

“Time cannot leach forgetfulness

When grief’s full heart is fed by fame.”

Over the portico of the Pantheon in Paris are these words in large letters, “to Great Men, The Grateful Fatherland.” Fellow Mississippians, I cannot repress the painful regret that it is not the proud privilege of Mississippi to be “the grateful fatherland” of the greatest Mississippian, and to keep holy watch and ward over the sacred dust of her most illustrious son. He was great to those who knew him best—those who were nearest to him in intimate, confidential companionship, and he will grow greater with the growing years. Caleb Cushing, in introducing him to a vast audience in Faniuel Hall, said he was “eloquent among the most eloquent in debate, wise amongst the wisest in council, and brave among the bravest in battle.” Senator Reagan, of Texas, the Postmaster General of the Confederate Government, said, “He was a man of great labor, of great learning, of great integrity, of great purity.” The great-hearted and marvelously eloquent Senator Benj. H. Hill, of Georgia, said: “I declare to you that he was the most honest, the truest, gentlest, bravest, tenderest, manliest man I ever knew.”

Greatest of Mississippians, the leader of our armies, the defender of our liberties, the expounder of our political creeds, the authoritative voice of our hopes and fears, the sufferer for our sins, if sins they were, and the willing martyr to our sacred cause,—we shall ever speak his name with reverence and cherish with patriotic pride the story of his matchless deeds. He died without citizenship here, but he has become a fellow citizen with the heroes of the skies.

Marvelous, many-sided, masterful man, his virtues will grow brighter and his name be writ larger with each passing century. Soldier, hero, statesman, gentleman, American,—a prince of Christian chivalry,—the uncrowned chief of an invisible republic of loving and loyal hearts, <—when another hundred years have passed, no intelligent voice will fail to praise him, and no patriotic hand will refuse to place a laurel wreath upon his radiant brow.

“Nothing need cover his high fame but heaven,

No pyramid set off his memories

But the eternal substance of his greatness,

To which I leave him.”