To the Editor of the Enquirer:

According to the regular course of legal proceedings I ought, in the first place, to urge my plea in abatement to the jurisdiction of the court. As, however, we are not now in a court of justice, and such a course might imply some want of confidence in the merits of my cause, I will postpone that enquiry, for the present, and proceed directly to the merits. In investigating those merits, I shall sometimes discuss particular points stated by the Supreme Court, and at others, urge propositions inconsistent with them. I pledge myself to object to nothing in the opinion in question, which does not appear to me to be materially subject to error.

I beg leave to lay down the following propositions, as being equally incontestable in themselves, and assented to by the enlightened advocates of the Constitution, at the time of its adoption.

1. That that Constitution conveyed only a limited grant of powers to the general government, and reserved the residuary powers to the governments of the States, and to the people; and that the tenth amendment was merely declaratory of this principle, and inserted only to quiet what the court is pleased to call “the excessive jealousies of the people;”

2. That the limited grant to Congress of certain enumerated powers only carried with it such additional powers as were fairly incidental to them, or, in other words, were necessary and proper for their execution;

And 3. That the insertion of the words “necessary and proper,” in the last part of the eighth section of the first article, did not enlarge the powers previously given, but were inserted only through abundant caution.

On the first point it is to be remarked that the Constitution does not give to Congress general legislative powers, but the legislative

powers “herein granted.” … 1st Art. of Const

So it is said in “The Federalist,” that the jurisdiction of the general government extends to certain enumerated objects only and leaves to the States a residuary and inviolable sovereignty over all other objects; that in the new, as well as the old government, the general powers are limited, and the States, in all the unenumerated cases, are left in the enjoyment of their sovereign and independent jurisdiction; that the powers given to the general government are few and defined; and that all authorities of which the States are not explicitly divested, in favor of the Union, remain with them in full force; as is admitted by the affirmative grants to the general government, and the prohibitions of some powers, by negative clauses to the State governments.

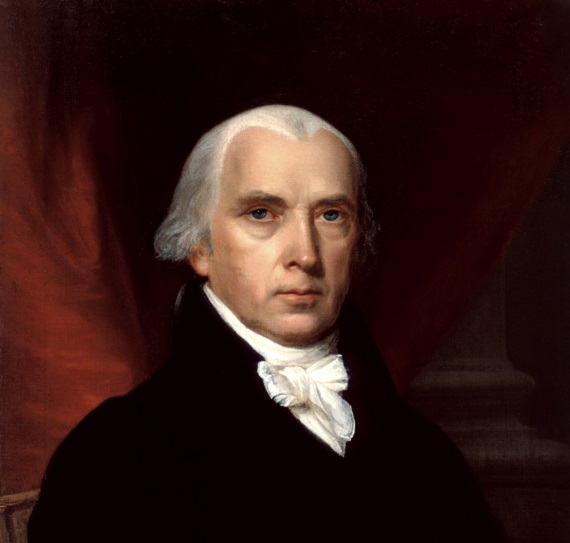

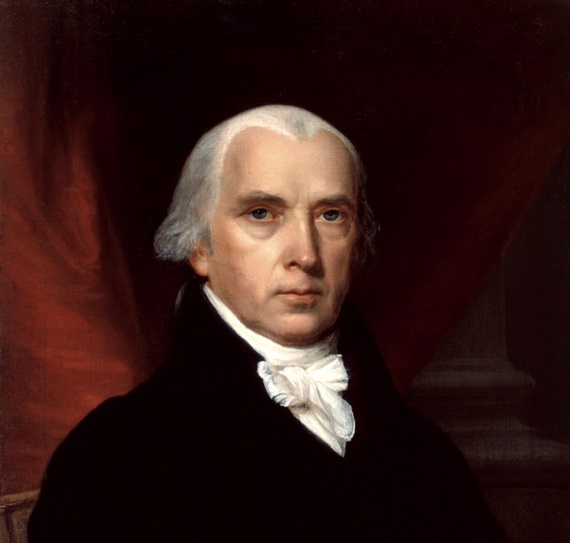

It was said by Mr. Madison, in the convention of Virginia, that the powers of the general government were enumerated and that its legislative powers are on defined objects, beyond which it cannot extend its jurisdiction; that the general government has no power hut what is given and delegated, and that the delegation alone warranted the power; and that the powers of the general government are but few, and relate to external objects, whereas those of the States relate to those great objects which immediately concern the prosperity of the people. It was said by Mr. Marshall that Congress cannot go beyond the delegated powers, and that a law not warranted by any of the enumerated powers would be void; and that the powers not given to Congress were retained by the States, and that without the aid of implication. Mr. Randolph said that every power not given by this system is left with the States. And it was said by Mr. Geo. Nicholas that the people retain the powers not conferred on the general government, and that Congress cannot meddle with a power not enumerated.

It was resolved in the legislature of Virginia, in acting upon the celebrated report of 1799 (of which Mr. Madison, the great patron of the Constitution, was the author), that the powers vested in the general government result from the compact, to which the States are the parties; that they are limited by the plain sense of that instrument (the Constitution), and extend no further than they are authorized by the grant; that the Constitution had been constantly discussed and justified by its friends, on the ground that the powers not given to the government were withheld from it; and that if any doubts could have existed on the original text of the Constitution, they are removed by the tenth amendment; that if the powers granted be valid, it is only because they are granted, and that all others are retained; that both from the original Constitution and the tenth amendment, it results that it is incumbent on the general government to prove, from the Constitution, that it grants the particular powers; that it is immaterial whether unlimited powers be exercised under the name of unlimited powers, or under that of unlimited means of carrying a limited power into execution; that in all the discussions and ratifications of the Constitution it was urged as a characteristic of the government, that powers not given were retained, and that none were given but those which were expressly granted, or were fairly incident to them; and that in the ratification of the Constitution by Virginia, it was expressly asserted that every power not granted by the Constitution remained with them (the people of Virginia), and at their will.

2. I am to show in the second place that by the provisions of the Constitution (taken in exclusion of the words, “necessary and proper” in the 8th of the 1st article) such powers were only conveyed to the general government as were expressly granted or were (to use the language of the report), fairly incident to them. I shall afterwards show that the insertion of those words, in that article, made no difference whatever and created no extension of the powers previously granted.

I take it to be a clear principle of universal law—of the law of nature, of nations, of war, of reason and of the common law— that the general grant of a thing or power, carries with it all those means (and those only) which are necessary to the perfection of the grant, or the execution of the power. All those entirely concur in this respect, and are bestowed upon a clear principle. That principle is one which, while it completely effects the object of the grant or power, is a safe one, as it relates to the reserved rights of the other party. This is the true principle, and it is an universal one, applying to all pacts and conventions, high or low, or of which nature or kind soever. It cannot be stretched or extended even in relation to the American government; although, for purposes which can easily be conjectured, the Supreme Court has used high sounding words as to it. They have stated it to be a government extending from St. Croix to the Gulf of Mexico, and from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean. This principle depends on a basis which applies to all cases whatsoever, and is inflexible and universal.

If, in relation to the powers of the general government, the express grants, aided by this principle under its true limitation, do not confer on that government power sufficiently ample, let those powers be extended by an amendment to the Constitution. Let us now do what our convention did in 1787, in relation to the articles of confederation. Let us extend their powers, but let this be the act of the people, and not that of subordinate agents. But let us see how far the amendments are to extend, and not, by opening wide the door of implied or constructive powers, grant we know not how much, nor enter into a field of interminable limits. Let us, in the language of the venerable Clinton, extend the powers of the general government, if it be necessary; but until they are extended, let us only exercise such powers as are clear and undoubted.

In making some quotations from the laws of nature, of nations, of war, of reason, and the common law, it will be seen that these establish not only the principle I contend for, but the limits under which the incidental powers are to be exercised. It is in this last relation that I ask the principal attention of the reader. While these limits must always, in a degree, depend upon the circumstances of every particular case, the cases I shall give the general character of the power. It will be seen that that power is always limited by necessity; which, although it may not be, in all cases, a sheer necessity, falls far short of the extensive range claimed, in this instance, by the Supreme Court. I need not say to the legal part of our citizens, that the exception proves the rule; nor that the allowance of a power up to a given limit, is a denial of it beyond it.

We are told by Vattel that “since a nation is obliged to preserve itself, it has a right to everything necessary for its preservation, for that the law of nature gives us a right to everything Without Which we could not fulfil an obligation: otherwise it would oblige us to do impossibilities, or rather contradict itself, in prescribing a duty and prohibiting, at the same time, the only means of fulfilling it.” Again, he tells us that a nation has a right to everything without which it cannot obtain the perfection of the members, and the State. Again, we are told, by him, that a tacit faith may be given by a prince, etc. And that “everything without which what is agreed upon, cannot take place,” is tacitly granted,—as, if a promise is made to an army of the enemy, which has advanced far into the country “that it shall return home in safety,” provisions are also granted, for they cannot return without them. * * * We are further told that in granting or accepting an interview full security is also tacitly granted. The provisions and the security are each of them a sine quo non of the fulfillment of the grant, or promise: they are both indispensable. So he tells us that if a man grants to one his house, and to another his garden, the only entrance into which is through the house, the right of going through the house passes as an incident, for that it is absurd to give a garden to a man, into which he could not enter. We are further told by this writer that the grant of a passage for troops includes everything connected with the passage, and without which it would not be practicable as exercising military discipline, buying provisions, etc.; that he who promises security to another by a safe conduct, is not only to forbear violating it himself, but also to punish those who do, and compel them to make reparation: that a safe conconduct naturally includes the baggage of the party, and everything necessary for the journey, but that the safest and modern way is, to particularize even the baggage: and that a permission to settle anywhere includes the wife and children, for that when a man settles anywhere he carries his wife and children with him, but that the case is different as to a safe conduct, for that when a man travels his family is usually left at home.

These examples quoted from the laws of nature, of nations, and of war, have a remarkable and entire coincidence with the principles of the common law, and show that great principles extend themselves alike into every code. In all of them the incidental power is limited to what is necessary: and in none of them is a latitude allowed, as extensive as that claimed by the Supreme Court.

The principle of the common law is, that when any one grants a thing he grants also that without which the grant cannot have its effect; as, if I grant you my trees in a wood, you may come with carts over my land to carry the wood off. So a right of way arises on the same principle of necessity, by operation of law; as, if a man grants me a piece of land in the middle of his field he tacitly and implicitly gives me a right to come on it. We are again told that when the law giveth anything to any one, it implicitly giveth whatever is necessary for taking or enjoying the same: it giveth “what is convenient, viz.: entry, egress and regress as much as is necessary.” The term “convenient” is here used in a sense convertible with the term “necessary” and is not allowed the latitude of meaning given to it by the Supreme Court. It is so restricted in tenderness to the rights of the other party. The rights of way passing in the case above mentioned, is also that, merely, of a private way, and does not give a high road or avenue through another’s land, though such might be most convenient to the purposes of the grantee. It is also a principle of the common law that the incident is to be taken according to “a reasonable and easy sense,” and not strained to comprehend things remote, “unlikely or unusual.” The connection between the grant and the incident must be easy and clear: the grant does not carry with it as incidents, things which are remote or doubtful.

These quotations from the common law are conclusive in favor of a restricted construction of the incidental powers. They show that nothing is granted but what is necessary.. .They exclude everything that is only remotely necessary, or which only tends to the fulfillment.

These doctrines of the common law control the present case. But it is immaterial, as I have already said, by what code it is to be tested. On this point there is no difference between them; for they all depend upon an inflexible and immutable principle. The common law, however, governs this case. That law is often resorted to, of necessity, in expounding the Constitution. * * * Many of the powers given by the Constitution, are given in terms only known in the common law. The authority of that law is universally admitted to a certain extent in expounding the Constitution. It is admitted both by the report of 1799, and by the Virginia Legislature of the same year, in relation to such parts thereof as have a sanction from the Constitution by the technical phrases used therin, expressing the powers given to the general governmnt, and also as to such parts thereof as may be adopted by Congress, as necessary and proper for carrying into execution the powers expressly delegated.1 Is not this admission full up to the very point of referring to that law in this case, and adopting the standard which it has established?

That law not only affords this standard, but it was wise in the Constitution to refer to a standard which is equally familiar to all the States, and is corroborated by the corresponding principles on every other code. By the common law the term incident is also well defined, as the examples I have quoted will show. It is the part of wisdom to define the terms as you go, or at least to refer to a standard which contains their definition. I have another preference for this code, and for the term “incident,” which it uses, and that is that that term is particular. The term “means” started up on the first occasion, is not only undefined, but is general; and “dolus latet in generalibus” (guile covers itself under general expressions). Why should the Supreme Court tramp up a term on this occasion, which is equally novel, undefined and general. Why should they select a term which is broad enough to demolish the limits prescribed by the general government, by the Constitution? I will now proceed to show that the terms “necessary” and “incidental” powers were those uniformly used at the outset of the Constitution, while the term “means” is entirely of modern origin. It is at least so when offered as a substitute for the term “incident” or “incidental powers.”

We are told in the Federalist that all powers indispensably necessary are granted by the Constitution, though they be not expressly; and that all the particular powers requisite to carry the enumerated ones into effect, would have resulted to the government by unavoidable implications, without the words “necessary and proper;” and that when a power is given, every particular power necessary for doing it is included. Again, it is said that a power is nothing but the ability or faculty of doing a thing, and that that ablity includes the means necessary for its execution.

It is laid down in the report before mentioned that Congress under the terms “necessary and proper” have only all incidental powers necessary and proper, etc., and that the only enquiry is whether the power is properly an incident to an express power and necessary to its execution, and that if it is not, Congress cannot exercise it: and that this Constitution provided during all the discussions and ratifications of the Constitution, and is absolutely necessary to consist with the idea of defined or particular powers: again, it is said, that none but the express powers and those fairly incident to them were granted by the Constitution.

The terms “incident” and “incidental powers” are not only the terms used in the early stages and by the friends of the Constitution, but they are the terms used by the court itself, in more passages than one, in relation to the power in question. The same terms are used by the Chief Justice in his “Life of Washington” (Vol 5, 293) as relative to the implied powers. So it is said by Mr. Clinton, in his rejection of the bank bill before mentioned, that the means must be accessorial and subordinate to the end. Mr. Clay also said on the same occasion that the implied powers must be accessorial and obviously flow from the enumerated ones. Having show the universal adoption of these terms, we will now recur to their real meaning. In Co. Litt. 151 b. (Coke on Littleton), an incident is defined, in the common law, to be a thing “appertaining to or following another as more worthy of principal.” So Johnson defines it to be “means following in beside the main design.” Can it be then said that means which are of an independent or paramount character can be implied as incidental ones? Certainly not, unless, to say the least, they be absolutely necessary.

Can it be said after this that we are at liberty to invent terms at our pleasure, in relation to this all-important question? Are we not tied down to the terms used by the founders of the Constitution; terms, too, of limited, well defined and established signification? On the contrary, I see great danger in using the general term now introduced; it may cover the latent designs of ambition, and change the nature of the general government. It is entirely unimportant, as is before said, by what means this end is effected.

3. I come in the third place to show that the words “necessary and proper,” in the Constitution, add nothing to the powers before given to the general government. They were only added (says “The Federalist“), for greater caution, and are tautologous and redundant, though harmless. It is also said in the report aforesaid, that these words do not amount to a grant of new power, but for the removal of all uncertainty the declaration was made that the means were included in the grant. I might multiply authorities on this point to infinity; but if these do not suffice, neither would one were he to arise from the dead. If this power existed in the government, before these words were used, its repetition or reduplication, in the Constitution, does not increase it. The “expression of that which before existed in the grant, has no operation.” So these words “necessary and proper,” have no power or other effect than if they had been annexed to and repeated in every specific grant; and in that case they would have been equally unnecessary and harmless. As a friend, however, to the just powers of the general government, I do not object to them, considered as merely declaratory words, and inserted for greater caution: I only deny to them an extension to which they are not entitled, and which may be fatal to the reserved rights by the States and of the people.

In my next number, Mr. Editor, I shall examine more particularIt some of the principles contained in the opinion of the Supreme Ckmrt.

Hampden.

From the Richmond Enquirer, June 15, 1819.