Maryland is steeped in the history of the American Union. She fiercely defended her position amongst the thirteen original states as a free, independent, and sovereign state. She was the last to accede to The Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union. The first article of the Maryland Declaration of Rights states, “That all Government of right originates from the People, is founded in compact only, and instituted solely for the good of the whole; and they have, at all times, the inalienable right to alter, reform or abolish their Form of Government in such manner as they may deem expedient.” [Emphasis added.]

Powerful words indeed!

Maryland’s tradition of self-governance and self-determination was laid bare as state legislatures and conventions met to determine the fate of their role in the Federal Union as conceived by their forefathers. Maryland along with nearly every northern and southern state fully comprehended the right of the people of each state to freely accede to join the Union as well as the right to secede from the Union. Eventually, eleven states seceded from the Union by May 1861.

The springtime of 1861 in Maryland was turbulent. Seven states had seceded from the Union and on April 15th Lincoln’s proclamation to raise 75,000 troops was issued. It said:

“Whereas the laws of the United States have been for some time past and now are opposed and the execution thereof obstructed in the States of South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Florida, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas by combinations too powerful to be suppressed by the ordinary course of judicial proceedings or by the powers vested in the marshals by law:

Now, therefore, I, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States in virtue of the power in me vested by the Constitution and the laws, have thought fit to call forth, and hereby do call forth, the militia of the several States of the Union, to the aggregate number of 75,000, in order to suppress said combinations and to cause the laws to be duly executed.”

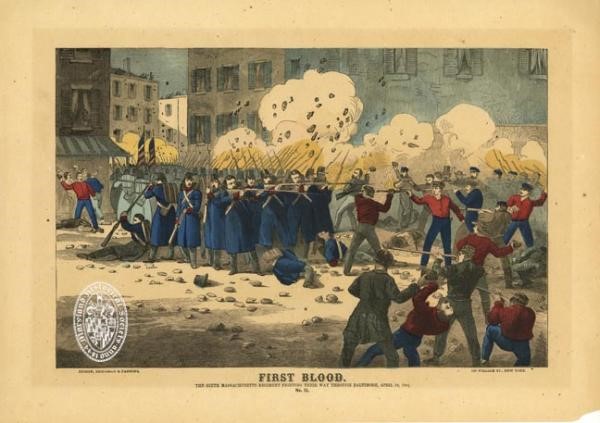

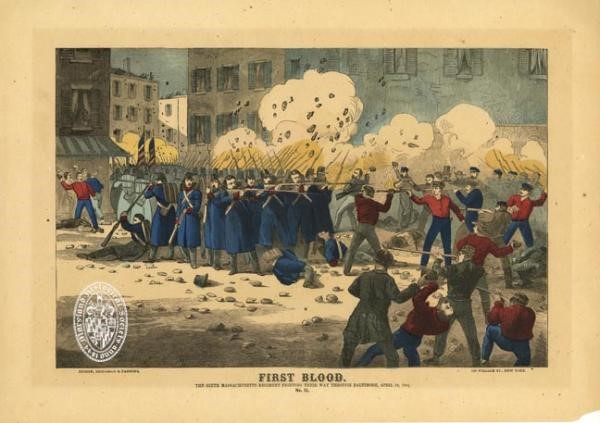

In Maryland, events took a turn for the worse. On April 19th word reached Maryland that Massachusetts troops were being transported through Baltimore. Maryland had not acquiesced to those troops entering her soil. Subsequently, riots broke out in Baltimore and hostilities between the Massachusetts troops and citizens of Maryland ensued. The Baltimore Board of Police tried to maintain the peace and ensure safe passage of the troops. Several soldiers and citizens were killed.

James Ryder Randall wrote the poem “Maryland, my Maryland” – a nine verse stanza – in honor of his friend, Francis Ward, who was killed by the 6th Massachusetts Regiment in Baltimore. The poem was first published the following week in a New Orleans paper and was later set to the tune of O Tannebaum by Jennie Cary. It was adopted as the state song of Maryland in 1939. The poem’s words reflect the tenuous nature in Maryland and the reality of what had been foisted upon the state by Mr. Lincoln.

The Free State of Maryland was no longer free.

Mr. Lincoln raised and quartered large standing armies in Maryland without her consent, made the military superior to and above the civil power, assumed command and regulations of the internal police and government of the State, seized upon and appropriated railroads and telegraphs, seized and searched vessels, forcibly entered the houses of citizens, deprived the people their right to bear arms, suspended the writ of habeas corpus, arrested citizens and transported them to other States for trial upon charges or pretend charges, taken the private property of the citizens, and the unauthorized stopping and searching of peaceable citizens and in some cases imprisoning them without due process.

The legislature met biannually but due to the popular outcry of the citizens Governor Thomas Hicks called the Maryland Legislature into special session. The legislature was unable to convene in Annapolis due to federal occupation and the special session was instead convened in Frederick, Maryland.

Numerous correspondences occurred between the Governor and the Lincoln administration and among various state departments and agencies. The Maryland General Assembly issued several reports in May and June including a report by the House of Delegates (later re-issued by the Senate with that body’s amendments) titled, Report of the Committee on Federal Relations in Regard to the Calling of a Sovereign Convention.

The report is twenty pages in length and its purpose was to address two pressing issues: (1) “the state of public affairs and (2) the remedy which it suggests to the people of the State for the perilous contingencies which surround them.” It was intended to address the need to call a sovereign State convention and address the issue of arming the state militia. The report is an exquisite composition on the purposes of Mr. Lincoln’s Proclamation, the Constitution and delegated powers, the ability to make war against a State and/or enforce the laws against states (rather than individuals as was intended by the Constitution), and other unconstitutional acts of usurpation.

There are several illuminating paragraphs as well as the resolutions reproduced below. The full report is truly insightful and many excellent points are made throughout it.

The President of the United States, by his Proclamation of the 15th of April, had called upon a portion of the States to place at his disposal the body of militia, to the number of seventy-five thousand men. The Proclamation was directed against the people of the newly-formed Southern Confederacy, and its purposes and policy were obvious, although its terms were technically shaped in conformity with the Act of Congress 1795… If a President of the United States, under the fraudulent pretence of suppressing unlawful combinations in Louisiana and Florida, could be permitted to call out troops, to be used for any purpose in Maryland or Virginia, no soil of any State would be free from invasion, and no right of the citizen anywhere would be secure against overthrow.

His Proclamation was regarded as a declaration of war against the Southern Confederacy – as a deliberate summons to the people of the two sections, into which his party and its principles had so hopelessly divided the land to shed each other’s blood, in wantonness and hate… Independently, too, of its wantonness and inhumanity, it was felt and known to be a gross violation of the Constitution, and without color of lawful authority. The people of the seceded States, whether constitutionally or unconstitutionally, had separated themselves from this government and established a federal government of their own, with all the forms of a constitution and all the substantial attributes of actual independence. Through their constituted authorities and in their collective capacity, as communities, they had withdrawn themselves from the Union – repudiated its laws and excluded its officers, of all sorts, from the exercise of all functions and jurisdiction. The United States government no longer had among them either courts to issue, or marshals to execute process. They had substituted their own courts and their own processes, to which they yielded cheerful obedience. The authority of the Federal Government was in fact dead within their limits.

To attempt to apply, under such circumstances, to a belligerent people, an Act of Congress, which was meant as a domestic remedy, in aid of civil process and to secure obedience to the laws under judicial proceeding – in States still recognizing the authority of the Union and the jurisdiction of its tribunals – was to trifle with the understandings of educated men. To issue a proclamation to three millions of free Americans, composing seven powerful States, and asserting the sacred and indefeasible right of self-government, with arms in their hands, and “command” them as “insurgents” to “retire peaceably to their respective abodes,” like a mob at a street corner, was an absurdity too gross to be here respectfully discussed… The Proclamation, therefore, meant war, and nothing but war. It could signify nothing else, and to attempt to cloak its meaning and purpose under the flimsy pretext of “executing the laws” and “suppressing unlawful combinations,” was but to cover up a flagrant usurpation with words.

Neither the Constitution nor the laws of the United States can be tortured into conferring the war-making power upon the President in any contingency.

The Maryland legislature concludes President Lincoln is invoking authority under the Act of Congress of 1795 (the Militia Act of 1792, revised in 1795) to suppress insurrections prohibiting courts and judicial processes to function within the seven seceded states though those seven states left the Union and were not under the jurisdiction of the United States but instead were under the authority of the government they constituted for themselves. The legislature concludes this is a declaration of war and the President has no war-making powers under the Constitution.

Moreover, take notice that the Proclamation explicitly enumerates the seven states and no other states.

Further buttressing the legislature’s position is the Constitution was ordained and established to act on individuals and not on states. Arguably, this is the most important and often overlooked difference between The Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union and the Constitution for the United States. The Articles of Confederation acted upon the States whereas the Constitution for the United States acts upon individuals. The Report addresses this point at length.

As early as the fifth day after the meeting of the Convention for the formation of the Federal Constitution, “the use of force against a State,” by the rest of the Union, as contemplated in the plan of Mr. Randolph, was denounced by Mr. Madison, and on his motion the resolution providing for it was indefinitely postponed by unanimous assent. Mr. Madison announced it as his deliberate opinion that “a union of the States, containing such an ingredient, seemed to provide for its own destruction.”… When Gen. Hamilton was called to express his opinion upon it, he asked, “How can this force be exerted on the States collectively? It is impossible; it amounts to a war upon the parties. Foreign powers, also, will not be idle spectators. They will interpose; the confusion will increase and a dissolution of the Union will ensue.” The reasoning was unanswerable, and the Constitution happily was not stained with the perilous folly, against which these two great statesmen so earnestly protested. There was not a discussion in the debates on the Federal Constitution, whether in the Convention which framed it or the State Conventions which adopted it, that does not confirm this view of its spirit and purpose. The essays of the Federalist are pregnant with demonstrations to the same effect, and there is no constitutional lawyer who does not know, that the whole theory of the Government is to act, through the courts, upon individuals, and not through the Army and Navy upon the States. [Emphasis added.] The brave and wise men who framed and upheld it, would have died in the breach before they would have submitted themselves to it upon any other basis. It could never have been adopted, it would never have been ratified, upon any understanding. The States would have endured anarchy, distracted counsels, and all the evils of the old Confederation, aggravated tenfold, before they would have surrendered themselves to any system in which the Federal Government, and least of all, the Federal Executive, was clothed with the constitutional power of coercing them by force of arms. They entered into a Constitutional Union, depending for its permanence upon the good faith and good feeling of its members, and deriving its strength from their consent only. They did not abandon themselves to the bayonets of military despotism enthroned upon popular majorities. [Emphasis added.] [S]ubjugated provinces could not be sister States, and a Federal Government, professedly Republican, maintaining the authority by armies, could not be other than the worst and most unprincipled and uncontrollable of despotisms. The South has entrenched itself upon the principle of self-government. It has offered to negotiate, peaceably and honorably, upon all matters of common property and divided interest, claiming only that three millions of people had a right to throw off a Government, by which they no longer desired to be ruled, and to live under another Government of their own choosing. Unless the American Revolution was a crime, the declaration of American Independence a falsehood, and every patriot and hero of 1776 a traitor, the South was right and the North was wrong, upon that issue.

The Report then addresses the request for troops and references letters of correspondence between the United States Government and the Governor of Maryland. Paradoxically, the U.S. Government correspondence conflicts with President Lincoln’s proclamation as the correspondence indicates the purpose for the requisition of troops from Maryland is to defend the capital and to protect the property of the citizens of Maryland. Those letters can be read here. The Report quotes the correspondence and addresses the issue.

[B]y the two letters of the Secretary of War, dated April 17, in which that gentleman informs him that “the troops to be raised in Maryland will be needed for the defence of the Capital and of the public property in that State and neighborhood.” “There is no intention”, the Secretary adds, “of removing them beyond these points.”.. The Proclamation of Mr. Lincoln, under which the troops of Maryland have been called into the field, is directed (as has already been observed) against the seceding States and none other. The Militia were summonsed to execute the laws and suppress unlawful combinations in South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas; and not in Maryland or the District of Columbia. The very requisition of the Secretary of war upon the Governor, is in direct and absolute contradiction to the assurance contained in his letter. The one asks for troops to be used in the South, and not at the Federal Capital, the other declares that their employment, at the Federal Capital and not in the South, is the only purpose contemplated… Whatever destiny the people of Maryland may be able or willing to shape for themselves, now or hereafter, the Committee would be pained to believe it possible, that a single citizen of the State could be forced or persuaded to take part, directly or indirectly, in the slaughter and subjugation of our Southern brethren and the overthrow of Constitutional Government by usurpation and brute force. If the Government desires to put an end to all doubts as to the safety of the Capital, it can do so at a word, by putting an end to its own purposes of coercing the South. [Emphasis added.]

The Report continues unabashedly to demonstrate additional usurpations of power by Mr. Lincoln in his proclamation of May 3rd to call out even more troops to increase the regular army and navy though the President has no constitutional authority to do so.

[R]eference is especially had to the Proclamation of the 3d of May, calling out over forty-two thousand additional volunteers, to serve in the militia for a period of three years, and increasing the regular force of the United States by an addition of nearly twenty three thousand men to the army and eighteen thousand seamen to the navy. The most unscrupulous advocate of the Administration and its policy, would be compelled to shrink from the task of pointing out any legal or Constitutional authority of any sort, for this unprecedented measure. The right of increasing the army and navy is one that belongs exclusively to Congress, and over which the President has no more Constitutional control then the humblest citizen… The Proclamation is therefore without any color whatever of right, and is as plain and bald a subversion of the letter and spirit of the Constitution and the laws, as ever was attempted by the military power, in any Government ostensibly free. The pretense of “existing exigencies” is but the shape in which military revolutions have always begun, since the prestige of free institutions has rendered it necessary, even for usurpers to make a show of apology for overthrowing them.

The following paragraph in the Report on Federal Relations is the most concise singular exposition of the state of affairs and circumstances the state of Maryland found herself in that tumultuous spring of 1861. These words are worthy of the statesman of the founding generation.

If ever a triumphant illustration could be given of the wisdom of our fathers, in providing by the constitution, that the government should operate upon its individual citizens through the laws, and not upon the States by military coercion, it is to be found in the fact, that the first administration daring to depart from this fundamental and consecrated principle, has rushed, in the short space of sixty days, into the assertion of absolute control over the whole military resources of the country, in open and reckless defiance of every legal and constitutional restraint. The Committee hazard nothing in saying, that there is not a citizen of Maryland, whatever be his political opinions, who must not shudder at the palpable and ominous presence of this usurpation, and who does not recognize, for the first time, in his own experience or the history of Maryland, that he is living and moving and holding his civil and political rights at the pleasure of an unrestricted military power, and subject to the arbitrary and anti-republican caprices of what is entitled, “military necessity”. For any man to be able to persuade himself, under such circumstances, that the policy of the administration ever meant peace and not war – the “enforcement of the laws,” – the “defence of the capital” – and not subjugation – requires a peculiarity of mental construction with which reason is at a loss how to deal. To suppose that a blockade of the whole sea cost, from the capes of the Chesapeake to the extreme borders of Texas, with a land army extraordinary of one hundred and fifty thousand men, and a naval increase of eighteen thousand, can be intended only in the aid of “the ordinary course of judicial proceedings, or the powers vested in the Marshals,” and is therefore within the scope of the President’s civil functions, and not of the war-making power, which only Congress can exercise, implies a facility of conviction, to which nothing can be regarded as impossible.

The Report closes with the following resolutions:

Whereas, in the judgment of the General Assembly of Maryland, the war now waged by the Government of the United States upon the people of the Confederate States, is unconstitutional in its origin, purposes and conduct; repugnant to civilization and sound policy; subversive of the free principles upon which the Federal Union was founded, and certain to result in the hopeless and bloody overthrow of existing institutions; and

Whereas, the people of Maryland, while recognizing the obligation of their State, as a member of the Union, to submit in good faith to the exercise of all the legal and constitutional powers of the General Government, and to join as one man in fighting its authorized battles, do reverence, nevertheless, the great American principle of self-government, and sympathize deeply with their Southern brethren in their noble and manly determination to uphold and defend the same; and

Whereas, not merely on their own account and to turn away from their own soil the calamities of civil war, but for the blessed sake of humanity, and to avoid the wanton shedding of fraternal blood, in a miserable contest which can bring nothing with it but sorrow, shame and desolation, the people of Maryland are enlisted, with their whole hearts, on the side of reconciliation and peace: now, therefore, it is hereby

Resolved by the General Assembly of Maryland, That the State of Maryland owes it to her own self-respect and her respect for the Constitution, not less than to her deepest and most honorable sympathies, to register this her solemn protest against the war which the Federal Government has declared upon the Confederate States of the South, and our sister and neighbor Virginia, and to announce her resolute determination to have no part or lot, directly or indirectly in its prosecution.

Resolved, That the State of Maryland earnestly and anxiously desires the restoration of peace between the belligerent sections of the country, and the President, authorities, and people of the Confederate States, having, over and over again, officially and unofficially, declared that they seek only peace and self-defence, and to be let alone, and that they are willing to throw down the sword, the instant the sword now drawn against them shall be sheathed, the Senators and Delegates of Maryland do beseech and implore the President of the United States to accept the olive branch which is thus held out to him; and in the name of God and humanity to cease this unholy and most wretched and unprofitable strife, at least until the assembling of Congress in Washington shall have given time for the prevalence of cooler and better counsels.

Resolved, That the State of Maryland desires the peaceful and immediate recognition of the independence of the Confederate States, and hereby gives her cordial assent thereunto, as a member of the Union; entertaining the profound conviction that the willing return of the Southern people to their former Federal relations is a thing beyond hope, and that the attempt to coerce them will only add slaughter and hate to the impossibility.

Resolved, That the present military occupation of Maryland, being for purposes, in the opinion of this Legislature, in flagrant violation of the Constitution, the General Assembly of the State, in the name of her people, does hereby protest against the same, and against the oppressive restrictions and illegalities with which it is attended; calling upon all good citizens, at the same time, in the most earnest and authoritative manner, to abstain from all violent and unlawful interference, of every sort, with the troops in transit through our territory or quartered among us, and patiently and peacefully to lave to time and reason the ultimate and certain re-establishment and vindication of the right.

Resolved, That under existing circumstances, it is inexpedient to call a Sovereign Convention of the State at this time, or to take any measure for the immediate organization or arming of the militia.

On May 14th, the Senate issued their report with a single amendment to these resolutions. The Senate amendment called for two four party delegations to be sent as Peace Commissioners to Washington and to the Confederate States. A separate report of the Peace Commissioners was issued by General Assembly on June 11, 1861. That report can be read here.

Lastly, another set of resolutions were issued by the General Assembly on June 22, 1861. Those resolutions can be read here. One resolution is of particular importance. That is the 2nd resolution which states – precisely what all the other states in the Union understood – That the right of separation from the Federal Union is a right neither arising under nor prohibited by the Constitution, but a sovereign right, independent of the Constitution, to be exercised by the several States upon their own responsibility.

Due to military occupation the state could not arm its militia for its own defense nor could the state convene a sovereign convention safely. Even though a convention was not called, several Maryland legislators were illegally arrested and imprisoned by the Government of the United States. If Maryland was not militarily occupied, undoubtedly a Sovereign Convention would have convened. The outcome of a convention is purely speculative, but if the presidential election of 1860 is any indication–Mr. Lincoln received approximately 2% of the total votes cast in Maryland–Maryland, like Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Arkansas would have left the Union because of Lincoln’s call to raise troops to coerce and wage war against the seven Southern states the seceded from the Union.

Mr. Lincoln faced a harsh reality. The four aforementioned southern states left only after the call to raise troops to conquer and subjugate the seven Southern states. The Maryland General Assembly articulated the gross constitutional usurpation of power in the Report on Federal Relations. Given Maryland’s geographic location the state would envelope Washington D.C., thus Mr. Lincoln forbade Maryland from determining her own fate in the Federal Union through military occupation.

Indeed, the despot’s heel was on thy shore.