Judged by the quality of the men it brought to power the eighteenth-century Virginia way of selecting political leadership was extremely good; but judged by modem standards of political excellence, it was defective at nearly every point. As for voting qualifications, there was discrimination against women, poor men, and Negroes. There was no secrecy in voting, and polling places—only one in each county—were spaced too far apart. The two-party system was not in existence. Local government was totally undemocratic, and few offices at any level of government were filled by direct vote of the people: only burgesses in the colonial period and not many other officers for many years after the Revolution. Such modern refinements of political processes as the nominating primary, initiative, referendum, popular recall, proportional voting, and mechanical voting machines were, of course, unknown.

Nearly every detail of the political processes of eighteenth-century Virginia has been repudiated; but, at the same time, the men elevated by those processes have come to be regarded as very great men. Here is a dilemma in an area of fundamental importance, and its resolution is no simple matter. Was eighteenth-century Virginia so full of great men that a random selection would have provided government with a goodly supply of great statesmen? If not, must it not follow that the selective system played an important part in bringing to the top the particular men who managed the public affairs of that day?

Any appraisal of the system that elevated the revolutionary generation of Virginia leaders to power must take account of the society and economy in which it operated. At that time Virginia was comparatively free from competing groups. True, there were tensions between planters and Scottish merchants, between adherents of the Crown and revolutionists, and between officials of the Established Church and dissenters; but in the main, eighteenth-century Virginia was remarkably homogeneous. The overwhelming majority of men were agriculturalists, differing in the scale of their operations more than in the nature of them. They were trying to get ahead on parallel rather than on conflicting lines. Nearly every burgess was a representative of agricu1ture; there was little else in Virginia that he could represent. Under these circumstances, those who achieved most in non-political life could be vested with political power without seriously endangering the interests of less successful men. It was more or less appropriate for the large planter to represent the small farmer, and the farmer accepted this leadership as natural and proper.

All this is not to say that gentlemen of eighteenth-century Virginia were less vain, less ambitious, or less selfish than men have generally been. They demonstrated an active interest in their own advancement when they decided to stand an election for the House of Burgesses, selected the county in which to offer themselves, treated the voters, cultivated influential men, and placed themselves before the free holders during the hours of decision. But the circumstances of the times diminished the opportunity for ambitious, selfish men to prey upon society through the use of political power. In this agrarian society government hardly touched man’s chief means of livelihood, agriculture. Those who gained control over the law-making processes therefore had little opportunity to enrich themselves at the expense of others.

This much is plain: the political system of eighteenth-century Virginia was admirably suited to the social order which existed in eighteenth-century Virginia. And the political devices used, no matter what their theoretical value for other times and places, made this political system work. The system brought such men as Washington and Jefferson into politics allowed them to reach the top. One device which is considered objectionable today, the colonial practice of letting a man sit in the Assembly for a county where he was not a resident, gave to Henry, Washington, and others their first opportunity to enter the House of Burgesses. Virginia profited by an early beginning of the careers of these men; and sectional tensions in Virginia were perhaps diminished by this practice which lasted until the Constitution of 1776. Though Washington lived in Fairfax County, he must have felt some obligations to the freeholders across the Blue Ridge in Frederick County who had sent him to the House. And there were others like him whose outlook in public matters was probably broadened because they were attached to the interests of more than one locality.

Another device, the practice of requiring voters to be property owners, is even more bitterly condemned by present day political standards; but the critics of the property-holding requirements for voting too often lose sight of the ideas and purposes behind the requirements and forget what they accomplished. They are usually interpreted as an attempt to disfranchise the poor and deliver government into the hands of men of property. But the words of the law itself, the modest amount of land required for voting, and the comments of contemporaries indicate that the prime object of the law was to restrict the political power of the very rich. As one Virginian expressed it, “the object of those who framed the constitution of Virginia was to prevent the undue & overwhelming influence of great landholders in elections,” by disfranchising their landless “tenants & retainers” who depended “on the breath & varying will” of these great men. And there was another object of more fundamental importance. It was, in the words of the Constitution of 1776, to enfranchise those men, and only those, who had a “permanent common interest with, and attachment to, the community.” The ownership of land was obviously not a perfect index in the eighteenth century, and it would be far less perfect now. But it must be remembered that the electorate which gave its assent to the political advancement of these Virginia leaders and which was at the foundation of government in revolutionary Virginia was drawn only from the men of property.

One might even argue that a combination of bad practices on election day in colonial Virginia—oral voting, treating, and long journeys to the courthouse—came nearer to producing a working democracy than have the more rational and sophisticated devices of a later day. The prospect of refreshments and of an exciting day in which the humblest voter could play his public part brought out a high percent of the electorate. The voter was given a simple task, and It was performed in a fashion that heightened his awareness of his political importance. In the colonial period his only duty was to elect burgesses, and sometimes he was called upon to elect them only once in three years. All of his political attention was focused upon choosing two men out of a list of three, four, or perhaps five candidates.

If he chose well, the voter lost little by trusting his representatives to select other officials. And if the voter’s judgment was sound, there was no reason why he should not make a good choice because he usually knew each of the candidates personally. In the colonial period the county was the largest constituency in Virginia and very few counties contained as many as a thousand ‘voters. In the years when the great generation of Virginians were beginning their political careers, the voter, whether he were wise or foolish, whether his motives were lofty or ignoble, usually knew what he was doing when he decided for one man and against another.

The voters, as voters generally are, were subjected to pressure in these elections. In colonial Virginia, as always, men of wealth and power exerted extraordinary influence in politics. But in the political system of eighteenth-century Virginia there was a frank and open recognition of this condition and a large measure of public knowledge as to how it was operating in particular cases. When Lord Fairfax supported Washington, his support was open and clearly recognizable; voters were not kept in the dark about the connection between the several candidates and the powerful men of the community. True, the voters were subjected to pressure and they were subjected to some forms of pressure that have since been minimized; but the pressure was comparatively open and unconcealed.

Pressure on the voters at election time came mostly from the county courts. These courts were neither efficient, learned, nor democratic. All too frequently they gave judicial decisions with little knowledge of the law, and they were beyond effective control by the people of the county. But paradoxially, these undemocratic courts served democracy well because they could resist pressures brought to bear on them from Williamsburg and later from Richmond. They served as a firm anchor of power down at the bottom of the political structure. Ancient custom, re-enforced after statehood by constitutional provisions, placed county government in some measure beyond colonial or state control.

The semi-independent status of the counties had long run effects on American history as well as immediate effects on the choice of political leadership in Virginia. Those Virginians who helped draft the Federal Constitution had lived under a quasi-federal system in colonial Virginia. They were thoroughly familiar with the little citadels of power located in each of the counties. They had seen the advantages of strongly fortified local positions during conflicts with the king’s representatives at Williamsburg. The experiences of these men in Virginia politics and government must not be forgotten when reflecting on the origins of the American federal system of government.

In assessing the importance of the political power of the county courts a comparison of the history of Virginia and South Carolina in the first half of the nineteenth century is valuable. Of the two, South Carolina, with its secret ballot, its more generous suffrage provisions, and its avoidance of self-perpetuating, gentry-controlled county courts was the more democratic: yet South Carolina became the more ardent defender of slavery, the advocate of nullification and secession, and, in the eyes of many, a great threat to the American democratic experiment.

The reasons for this apparent paradox are complex; but among them is the fact that South Carolina’s government, though more democratic than Virginia’s, was much more centralized. The foremost champion of states rights had made scarcely any provision for county right—certainly none equal to those in Virginia. There were no autonomous local offices in South Carolina where Union men could entrench themselves and live out the storm of the nullification controversy. The party that gained control over state government was able to deprive its opponents of nearly every office and instrument of power. In Virginia, in contrast, men and parties could win or lose power in Richmond without the county courts being much shaken by these changes. The magistrates could continue to exert much influence over the choice of representatives in the legislature. So long as the courts continued, Virginia never experienced a drastic political revolution; power was never seized by inexperienced men; and the people were never brought under the control of a centralized power. The courts were undemocratic, but they served democracy well.

Such vestiges of aristocracy in eighteenth-century Virginia as property qualifications for voting, oral voting, the power of the gentry in elections, and the arrogation of virtually all offices, local and state-wide, by the gentry, are contrary to twentieth-century principles and ideals of democracy. It is nevertheless certain that the high quality of Virginia’s political leadership in the years when the United States was being established was due in large measure to these very things which are now detested. Washington and Jefferson, Madison and Monroe, Mason, Marshall, and Peyton Randolph were products of the system which sought out and raised to high office men of superior family and social status, of good education, of personal force, of experience in management; they were placed in power by a semi-anstocrat1c political system.

All this is not to say that the electoral processes of colonial Virginia would be good for another time and place. But these considerations suggest that the path of political change needs occasional re-examination to see whether innovations have worked as well as their advocates prophesied and to search for useful elements in outmoded systems—values that may have been unwittingly destroyed and forgotten.

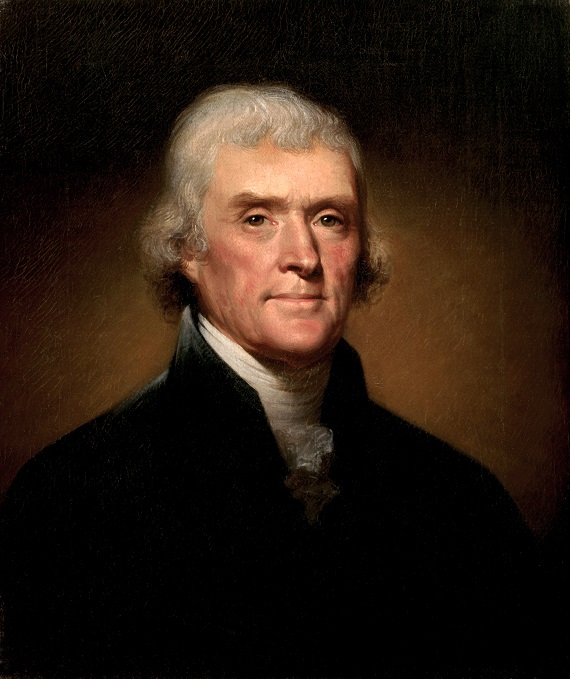

As a matter of fact, the undemocratic features of eighteenth-century Virginia politics did not go uncriticized in their own day. Thomas Jefferson, who was a member of the gentry and whose rise to power was through the channels controlled by the gentry, was nevertheless an out spoken critic of the arrangements to which he owed so much. His criticism stemmed in part from his belief that the gentry was sometimes an obstacle to progress. He blamed the justices for obstructing his plan to establish publicly supported elementary schools, explaining that “the members of the [county] court are the wealthy members of the counties; and as the expenses of the schools are to be defrayed by a contribution proportioned to the aggregate of other taxes which every one pays, they consider it as a plan to educate the poor at the expense of the rich.”

This experience reinforced Jefferson’s long-standing dislike for the monopoly of power over local government by a small, self-perpetuating body of men who came nearly always from a small number of leading families. Since the preeminence of these families was based on their large holdings of land, Jefferson devised a plan to whittle down their political power by diminishing their economic power. He drafted legislation that abolished entails and primogeniture, and he took much pride in thus laying “the ax to the foot of pseudo-aristocracy.”

Two things must be remarked about Jefferson’s attack upon the political leadership of the Virginia gentry. In the first place he was seeking a gradual rather than a sudden change. Of more importance, in fact of supreme importance, he showed no disposition to leave a vacuum in political leadership. The principle of relying on heredity to produce leaders—and this is what he meant by the term “pseudo-aristocracy”—he distrusted not because this principle was then working badly but because he believed it must in the long run work badly. He therefore sought to destroy this method of finding leaders; but with equal earnestness he strove to persuade his fellow Virginians to adopt another plan that would discover and prepare for public responsibilities what he called the “natural aristocracy.”

To discover and train political leaders Jefferson put his faith in an educational system of his own devising. Not much of his plan was adopted in his day, and since his day the plan has never been tried in America; for the Jeffersonian plan was more than a hierarchy of state-supported schools devoted to educating youth. An integral part of it was a series of screenings that would permit only the most exceptional youth to proceed from grade to grade until he reached the highest level of state-supported education. It began with small, local schools where boys would be given three years of elementary education in reading, writing, and arithmetic. Each year “the boy of the best genius, in the school, of those whose parents are too poor to give them further education,” was to be sent up to one of the twenty grammar schools to be established in the state. Here there was to be a second rigorous selection. After trial of a year or two, the ablest boy was to be chosen out of all who came to each school in a given year. He was to be “continued six years, and the residue dismissed. By this means,” so Jefferson observed, “twenty of the best geniuses will be raked from the rubbish annually, and be instructed, at the public expense, so far as the grammar schools go.” Even this was not the end. There was to be a third screening after the six years of grammar school, and only those who passed this final test were to be educated at state expense at the university.

From the standpoint of the twentieth century, Jefferson’s plan seems severely if not harshly rigorous. Nearly all who entered the lowest grades would be dropped by the wayside before the highest level of education was reached. But it must be remembered that Jefferson was destroying no educational opportunity then in existence. In his day parents paid for the education of their children, and be would let them continue to do so as much as they wished. Instead of subtracting from this arrangement, he would add to it the opportunity for every child, no matter how poor, to receive an elementary education; and if the child proved to be superlatively able, he would receive without cost the most complete formal education that Jefferson could devise. To the eighteenth century, Jefferson’s plan seemed to be a long and generous step forward; it was too much of a step for his Virginia contemporaries to take.

Jefferson was doubtless pleased by the thought that children of poor parents would be greatly helped by his plan. But in his public utterances he emphasized public benefits rather than assistance to needy persons. The state, he reasoned, should support education because education would benefit democracy. His plan would give at least the elements of education to all voters, and in its upper brackets it would train “able counsellors to administer the affairs of our country in all its departments, legislative, executive and judiciary, and to bear their proper share in the councils of our national government.” By this system “worth and genius” would be “sought out from every condition of life, and completely prepared by education for defeating the competition of wealth and birth for public trusts.”

The destructive half of Jefferson’s great plan for revising the quality of political leadership was adopted; steps were taken to end leadership by the aristocracy of birth and wealth. But the constructive half of his plan, which sought to fill office from the natural aristocracy of talents and training was not adopted. No one knows whether his whole plan would have worked, for it has never been tried. However, the plan itself seems to have had one glaring defect in it. His program might have discovered and trained talented men for public life, but Jefferson did not come to grips with the problem of how to get these men into office. The system he helped to destroy, despite all of its theoretical defects, actually put superior men in office. At this point in his own program, Jefferson is silent.

More important than any of the details of Jefferson’s plan is the fundamental assumption behind it. The author of the great assertion “that all men are created equal” had no faith in the equal fitness of all men for political leadership. His educational plan was based on the assumption that men are unequal in natural talents and in the use to which they put such talents as they have. His political philosophy had as a cornerstone the idea that a democracy should be led by the best trained of its ablest men. Democracy, according to Jefferson, must have this kind of an aristocracy to lead it.

Although Jefferson’s contemporaries did not support his plans for discovering and training superior men for office, they agreed that society needed the leadership of its ablest men and that it was the duty of men of this kind to seek and to hold office. Robert Munford made one of the characters in The Candidates declaim: “But, sir, it surely is the duty of every man who has abilities to serve his country, to take up the burden, and bear it with patience.” On the stage of real life this sentiment was echoed to Jefferson himself. Under a heavy load of domestic anxiety and distress, he wrote to Speaker John Tyler that he could not take the seat to which he had been elected in the Assembly. Tyler responded: “I suppose your [reasons] are weighty, yet I would suggest that good and able men had better govern than be governed, since tis possible, indeed highly probable, that if the able and good withdraw themselves from society, the venal and ignorant will succeed.”

Nearly two centuries have passed since these men entered public life. In this time democracy has made great gains in America chiefly in the period that bears the name of Andrew Jackson. The number of voters has multiplied, elective offices have increased, the two-party system has evolved, and nominating and electoral techniques have been perfected. The goal of democracy has been lengthened and broadened to include new groups of oppressed or unfortunate people and to give help and assistance in ever widening areas of life. The importance attached to this great and complex movement by American historians is demonstrated by the host of articles and books with such titles as the Growth of Democracy, the March of Democracy, the Age of Democracy, the Frontier and Democracy, and the Evolution of Democracy.

Those who have written under these titles have said very little about mistakes and losses along the road of the democratic movement, perhaps because attention to these things might seem to imply disloyalty to democracy itself. But surely no one could object if Washington and Jefferson, Madison and Marshall spoke plainly about losses as well as gains in American self-government since their age. It would be presumptuous, of course, to attempt to speak for them; but surely it is not presumptuous to point out elements in their political system that seem to have been lost sight of or at least minimized with the passage of the years.

Their system of self-government was based on the idea that democracy and aristocracy are not mutually exclusive, and that both of these can and ought to be used by a selfgoverning people. In eighteenth-century Virginia the generality of men enjoyed certain political privileges and had certain political duties to perform, but the higher and more difficult political duties were placed upon men who stood above the general level. It was perhaps inevitable that as the privileges and duties of the common man were increased in later years, especially in the Jacksonian period, there should be a declining faith in the usefulness of aristocracy in politics and a greater self-confidence on the part of the average citizen in his own ability to hold office. And it has perhaps been natural for historians to write more about the growth of democracy than about the decline of aristocracy in American history. But there is no reason to think that the great generation of Virginians regarded all men as political equals. They did not believe that a man who was qualified to vote was therefore fit to hold office. Jefferson’s words and the political practices of his generation of Virginians plainly say that there is a place for a certain kind of aristocracy as well as a place for democracy in self-government.

Finally, the political system of colonial Virginia warns against too much preoccupation with the mechanics of democracy. The gentlemen-politicians of the eighteenth century showed little interest in reforming the machinery of self-government though the machine they used was by modern standards seriously defective. Since their day each generation has tried to improve and refine political processes. The caucus system of making nominations was evolved. In time it was replaced by the convention, and the convention by the primary. The secret ballot, universal manhood suffrage, woman suffrage, the direct election of United States senators and other officials previously appointed or indirectly elected—these and other changes have been made in the faith that each would bring democracy closer to perfection. Undoubtedly, many of these changes have been improvements; but perfection has not been reached. Perhaps Americans in their intense preoccupation with improving the form of self-government have forgotten more important matters.

It is worth recalling that this generation of Virginians did not delay doing essential tasks until they could reshape and perfect the political instruments at hand. They were not ignorant of some of the defects and crudities of their political processes; but they never lost sight of large public issues while they tinkered with the machine. They were wise enough to know that it could never be perfected to such a point that it would automatically turn out a good product. Rather, they regarded it as nothing more than an instrument that men could use, or fail to use, to accomplish good purposes. To them democracy was not like a snug house, purchased in full with a heavy payment of sacrifice at the moment of its establishment, and then to be enjoyed in effortless comfort ever after. Their concept of self-government included the idea that it was a burden, valuable but heavy, which must be borne constantly. Carrying this burden was to them more important than refining the forms of political processes; for they knew that if they or their successors ever laid down the burden, or in weariness permitted it to be taken from their shoulders by more willing but less worthy men, self-government would come to an end. They knew no way for democracy to work except for men of good will to labor incessantly at the job of making it work.

This essay is the concluding chapter of Sydnor’s classic work, American Revolutionaries in the Making.