This essay is taken from The South in the Building of the Nation Series, Vol. 4 The Political History.

THE political theory on which the Southern states in 1860 and 1861 based their right to withdraw from the Union was not the sudden creation of any one man, or of any one group of men. Like other ideas that have played a prominent part in history, it was a gradual evolution from earlier and less elaborate conceptions. Its history runs back to colonial days, and its origin may be traced in the desire for independent action which led the early settlers into the wilderness. This was the guiding impulse in their long struggle against external control. Sometimes this struggle was against political control, sometimes against religious, sometimes against commercial. Usually it was directed against what might roughly be called the central government of their day—parliament and the king; and when other measures failed, it finally took the form of definite separation and independence. Occasionally the struggle was local, growing out of discontent with the government of some particular colony, and resulting either in open resistance, as in the case of Bacon’s rebellion, or in the more or less peaceful withdrawal of a portion of the inhabitants and the founding of new and separately organized communities, as in the case of Connecticut and Rhode Island. On other occasions the dissatisfaction in the older colonies was largely economic and the withdrawal took the form of that western movement in search of better opportunities which laid the foundation of future states across the Alleghany Mountains.

The theory on which these struggles were based lay vague and shapeless in the colonial mind for many years. In fact it took more precise form only as occasion after occasion demanded greater definiteness. The Stamp Act, for example, brought forth from all parts of the country the clear-cut statement that as Englishmen the colonists would not be taxed by others. The succeeding acts of the English government brought out more and more clearly the statement that they demanded in the largest possible sense as their English heritage the general right of making and administering their own laws. When finally this struggle took the form of withdrawal from England and reorganization, their theory took its definite shape from the political philosophy of the time, which rested on the doctrine of the natural rights of man, and found its most perfect expression in the Declaration of Independence, and especially in the statement that when a government becomes oppressive “it is the right of the people to alter or abolish it, and to institute a new government.”

The Right of Revolution.

Obviously this theory was concerned largely with the rights of the individual, and the final remedy for misgovernment was found in revolution. Nor was this attitude of mind confined to colonial days. It was the thought, misapplied perhaps, but none the less real, that animated Shay’s rebellion in Massachusetts, and the attempt to establish the separate state of Franklin in the western part of North Carolina—both during the critical period immediately after the Revolution. It was the philosophy of the western Pennsylvanians who, during Washington’s administration, resisted the internal revenue tax, because they regarded it as oppressive.

This philosophy had at least the virtue of simplicity, and perhaps for that reason long continued to find advocates among those who deemed themselves oppressed by the government. But gradually there grew up side by side with it a modified form of the theory, which concerned not the individual, but the state in relation to the larger political body of which it might be a part, and found in secession its final remedy when that relationbecameunbearable. Itcame into existence when the colonies began to combine in the face of common dangers. At first it was little more than the theory of revolution applied to a union of colonies. Thus the earliest, and in some respects the most important, of these unions was the New England Confederation, roughly speaking a century before the Revolution. It professed to be a perpetual union, yet it was no uncommon thing for the delegates of one of its members to threaten to secede. The Albany plan of union, which was proposed in 1754, was to be ratified by parliament as well as by the separate colonies. Yet Franklin, its chief advocate, dreaded the danger of secession and said “as any colony, on the least dissatisfaction, might repent of its own act, and thereby withdraw itself from the Union, it would not be a stable one, or such as could be depended on.”

Under the Articles of Confederation the threats of secession were loud and deep; but the theory continued to be little more than the doctrine of the right of revolution. When Congress seemed on the point of permitting Spain to close the Mississippi for twenty-five years in return for certain commercial concessions, Kentucky, which was at that time only a part of Virginia, threatened to withdraw from the Union if the river were closed, while on the other hand threats were made that the group of New England states would do so if their commercial advantages were sacrificed to save the river. Neither side in such controversies seemed to think it necessary to give any legal explanation of its right to withdraw from the Union, which was commonly supposed to be a perpetual one.

Even the adoption of the constitution seemed at first to make little difference. Twenty-five years of disintegration partly under English mismanagement and partly under the weak control of the confederation, had thoroughly discredited all national government; and it took time for the truth to get abroad that secession was now a more serious matter. Even Hamilton was uneasy, and during the debate over the assumption of the state debts in the first congress spoke to Jefferson of the danger of a “separation of the states.” Federalists in New England spoke of secession when it seemed possible that Jay’s treaty might not be confirmed, and in 1796 Lieutenant-Governor Wolcott of Connecticut, referring to the possibility of the election of Jefferson to the presidency, said, “I sincerely declare that I wish the Northern states would separate from the Southern the moment that event shall take place.” On the other hand when the Federalists seemed to be tightening their hold on the government, a Republican, John Taylor, of Virginia, wrote to Jefferson suggesting the withdrawal of Virginia and North Carolina. Jefferson opposed the suggestion, but his reply discussed the matter purely as a question of policy. “If,” he writes, “on a temporary superiority of the one party, the other is to resort to a scission of the Union, no Federal government can ever exist.”

The Kentucky Resolutions.

In all these cases secession seems to have been thought of as a matter of practical wisdom or unwisdom, and the theory received little attention. Yet in six months from the time when he wrote to Taylor the letter referred to above, Jefferson was formulating the Kentucky Resolutions, which set forth more elaborately a doctrine of state rights that was frequently referred to in after years as furnishing a legal basis for nullification and secession. But famous as they are, they, like the Declaration of Independence, owe their reputation more to their author’s wonderful gift of expression than to what was new in their thought or philosophy. They set forth the theory that the government was founded on a compact between the states, by which certain specified powers were delegated to the central government, and all others were reserved to the states, that “the government created by this compact was not made the exclusive or final judge of the extent of the powers delegated to itself, since that would have made its discretion and not the constitution the measure of its powers, but that as in all other cases of compact among parties having no common judge, each party has an equal right to judge for itself as well of infractions as of the mode and measure of redress.”

In the first part of this theory there was nothing new. Right or wrong, the idea that the government was formed by a compact between the states was perfectly familiar to those who had taken part in the constitutional convention or had followed the debates that preceded its ratification. The question as to what powers had been delegated to the new government had been thoroughly discussed in Congress and out of it. The question as to who should judge of infractions and of the mode and measure of redress had not attracted so much attention. Madison had written in the Federalist, “It is true that in controversies relating to the boundary between the two jurisdictions, the tribunal which is ultimately to decide, is to be established under the general government.” But he did not seem to think that this was the only and ultimate remedy, for in a later number of the Federalist he says, that in cases of encroachment by the central government “there would be signals of general alarm. Every government would espouse the common cause. A correspondence would be opened. Plans of resistance would be concerted. One spirit would animate and conduct the whole. The same combinations, in short, would result from an apprehension of the Federal, as was produced by the dread of a foreign yoke; and unless the projected innovations should be voluntarily renounced, the same appeal to a trial of force would be made in the one case as was made in the other.” This was the ultimate right of revolution, yet it was in the last analysis what was referred to by Jefferson’s statement that each had “a right to judge for itself as well of the infractions as of the mode and measure of redress,” which was after all the old doctrine of natural rights of individuals, under a government established by compact, now applied to states under a general government, likewise established by compact. Nor was this comparison a new one. It had been often made, as for example by Wilson in the Pennsylvania convention, when he said, “When a single government is instituted, the individuals of which it is composed surrender to it a part of their natural independence, which they enjoyed before as men. When a confederate republic is instituted, the communities in which it is composed surrender to it a part of their political independence which they formerly enjoyed as states.” Jefferson believed that the Federalists, who were in possession of the government, were planning to override the constitution and establish a despotism over the states, and in these resolutions he claimed for them the same right to resist that he had in the great declaration asserted for individuals under oppression. In each case he regarded it as a “natural” right.

It is needless to call attention to the fact that Jefferson did not propose to push this doctrine at once to a final test. His purpose was to affirm important principles “and leave the matter in such a train as that we may not be committed to push matters to extremities, and yet may be free to push as far as events will render prudent.”

The Federalists and Secession.

The resolutions called forth a heated discussion. The Federalists generally denounced them and insisted that differences arising between a state and the National government should be settled by the national courts. Yet within a few years serious threats of secession were made by leaders of that party. For reasons which it is not necessary to review they opposed the annexation of Louisiana. They now became strict constructionists of the constitution, and denied the right to buy Louisiana, or to admit any part of it as a state without the consent of the original thirteen. “Suppose,” said they, “in private life, thirteen men form a partnership, and ten of them undertake to admit a new partner without the concurrence of the other three, would it not be their option to abandon the partnership after so palpable an infringement on their rights? How much more so in the political partnership!” The legislature of Massachusetts in 1804 resolved that the annexation “formed a new confederacy, to which the states united by the former compact are not bound to adhere.” When in 1811 the admission of the state of Louisiana was under discussion, Quincy said, “If this bill passes, it is my deliberate judgment that it is virtually a dissolution of the Union; that it will free the states from their moral obligations; and, as it will be the right of all, so it will be the duty of some, definitely to prepare for a separation—amicably if they can, violently if they must.”

This idea was certainly as old as the days of the confederation, for Madison said, in the constitutional convention, referring to the confederation, that “a breach of any one article by one party, leaves all other parties at liberty to consider the whole convention as dissolved.”

The Federalists of New England, who distrusted the Republican leaders and suspected them of straining the constitution in order to perpetuate their hold on the government, found in the War of 1812 new occasions for discontent. In 1809 they had pronounced the embargo unconstitutional, and threats of separation had been heard. This action was repeated when it was again imposed during the war. The action of the government in regard to the state militia raised a similar protest. So strong was the opposition developed that Joseph Story wrote at the beginning of the war, “I am thoroughly convinced that the leading Federalists meditate a severance of the union, and that if public opinion can be brought to support them they will hazard a public avowal of it.” Toward its close Pickering, one of the leaders of the discontents, said, “I have even gone so far as to say that the separation of the Northern section of the states would be ultimately advantageous.”

The Hartford Convention.

Under such circumstances it is not surprising to find the Hartford convention adopting the philosophy of the Kentucky and the Virginia Resolutions, and stating, “that acts of congress in violation of the constitution are absolutely void,” and that “in cases of deliberate, dangerous, and palpable infractions of the constitution, affecting the sovereignty of a state, and the liberties of the people, it is not only the right, but the duty of such a state to interpose its authority for their protection, in the manner best calculated to secure that end.” The most interesting statement of all is perhaps this: “When emergencies occur which are either beyond the reach of the judicial tribunals, or too pressing to admit of the delay incident to their forms, states which have no common umpire must be their own judges, and execute their own decisions”—a doctrine that comes very close to that part of the Kentucky Resolutions which had been most severely condemned by the Federalists.

How far they intended to push these theories in practice is now hard to determine, as the war ended almost immediately and the coming of peace removed many of their grievances. The report of the convention said, “A severance of the Union by one or more states against the will of the rest, and especially in a time of war, can be justified only by absolute necessity.” But it also spoke of the necessity of “direct and open resistance” when abuses go too far.

The Federal Judiciary.

In dealing with the theories of this period it is necessary to remember that the extent of the jurisdiction of the Federal judiciary was still a subject of great doubt. It had at first occupied a position of no great dignity or influence, and had seemed anxious to avoid being drawn into politics. Not until after the war of 1812 did the influence of Marshall make itself fully felt in the series of decisions which did more, perhaps, than any other thing to win for it popular recognition as the final judge of the constitutionality of all laws and acts.

This increase in the power of the judiciary, which Jefferson described as “like gravity, ever acting*** gaining ground step by step, and holding what it gains,” was not made without vigorous opposition. New York, Virginia, Ohio, and other states were through important decisions forced to recognize its growing power. Yet none of these contests brought out any new theories of secession. Even Georgia, which carried its resistance farthest, did little more than deny the right of the Federal courts to decide a dispute between a state and the Federal government —a position which, with the support of President Jackson, it forcibly maintained.

Calhoun and State Rights.

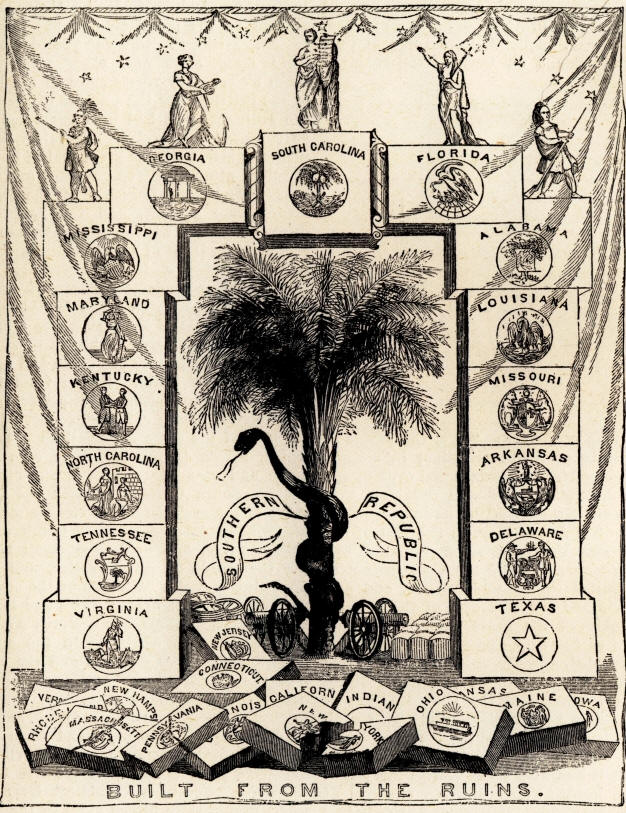

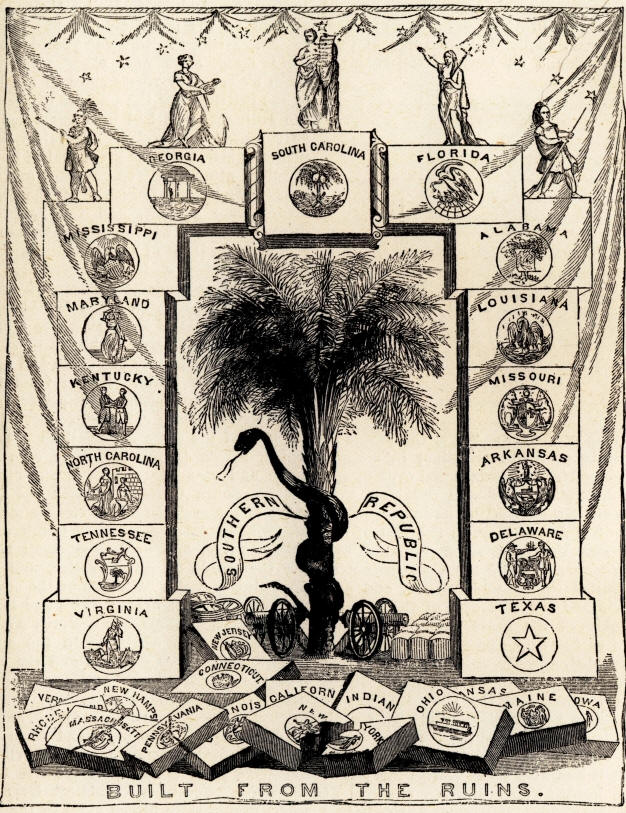

But with the passage of the tariff bills of 1828 and 1832 the growing tendency on the part of the National government toward a loose construction of the constitution aroused an opposition in the Southern states that seriously threatened forcible resistance and possible secession. This opposition was strongest in South Carolina, and called forth in that state an exposition of the theory of state rights, nullification, and secession which is usually associated with the name of Calhoun because of the great clearness and ability with which he stated it. Yet in its main features it closely resembled the doctrine of the Kentucky and the Virginia Resolutions. Indeed, its advocates insisted, perhaps unduly, on this resemblance.

Like them, it maintained that the Federal government was created by a compact between the states, which delegated certain specified powers to the general government and reserved all other powers to the states, that the Federal courts were not the final arbiter as to whether the Federal government assumed powers not given it, but that each state had the right to judge of the infraction and of the mode of redress. In these points they agree, but the philosophy that sustains the argument somewhat differs. In the phrases of Jefferson and between the lines one detects the philosophy of Locke and of the rights of man. With him all government originates in compact and the rights of the states in the government which they formed are the same as the rights of individuals in any government—the right to resist oppression. Calhoun expressly disbelieved in the dogma that all governments arose out of a state of nature by compact between individuals. With him the rights of the states grew out of the fact, which he took great pains to establish, that the constitution establishing the Federal government was adopted by states which were at that time sovereign and which remained sovereign. Jefferson seems to have thought, as did Madison and others, that on entering the Union each state surrendered a part of its sovereignty, and that thereafter the Federal government and the several states were each sovereign in its own domain. Calhoun maintained, as others had done before him, that sovereignty was indivisible and that, although the states delegated to the Federal government the right to exercise certain powers, yet each reserved its sovereignty entire and had the right of a sovereign state to resist the attempt of any one to exercise over it powers that it had not granted, and that in case such an attempt were made by the Federal government, each state had the right, in virtue of its undiminished sovereignty, to nullify the act, to resist its enforcement, and even to repeal its ratification of the compact and withdraw from the Union. The idea that the Federal judiciary was the proper arbiter in disputes as to what powers had been delegated he rejects on the same ground that Jefferson had given—that this would make a part of the Federal government the judge of a dispute to which it was a party. And he further added that the increase of authority which the Supreme Court of the United States had in recent years assumed was unconstitutional, as it was not intended to decide such matters.

The idea that the states were sovereign did not originate with Calhoun. He merely elaborated it more fully, and perhaps more skillfully, than anyone else had done. As far back as 1803 Tucker, of Virginia, in an edition of Blackstone, had said, in explaining the relation of the states to the Federal government, “Each is still a perfect state, still sovereign, still independent, and still capable, should occasion require, to resume the exercise of its functions, as such, to the most unlimited extent.” Moreover, it is probable that Patterson, of New Jersey, voiced the opinion of most of the delegates to the constitutional convention when he said, “We are met here as the deputies of thirteen independent states, for Federal purposes.” Nor can there be any reasonable doubt that at the time of the adoption of the constitution most people thought of it as adopted by the states separately, or, as the more precise among them even then expressed it, by the people of the several states. This idea was admirably put by Madison in the Virginia convention, when he said, “Who are parties to it? The people—but not the people as composing one great body; but the people as composing thirteen sovereignties.”

But no one else analyzed so keenly as did Calhoun the effect of this ratification on the sovereignty of the states. No one else insisted so clearly on the absurdity of the idea which had been common with many earlier writers, that the delegation of certain powers by a state to the central government meant the giving up of a part of its sovereignty.

The Divergence of the North and the South.

Many other incidents called forth threats of secession both in the North and in the South, as, for example, the Missouri Compromise, the abolition movement, the annexation of Texas, the question of slavery in the lands acquired by the war with Mexico, the struggle for Kansas, the John Brown raid, the election of Lincoln, and finally the use of force against the seceding states. But none of these, with the possible exception of the last, brought out any new development in the theories already elaborated. To the historian the most significant fact observed in studying them is the drifting apart of the two sections in their theory as to the nature of the government. Roughly speaking, during the thirty years immediately preceding the war the belief in state sovereignty became more and more general in the South, so that when secession finally came, while many Southerners questioned openly its practical wisdom, few doubted its legality. On the other hand, in the North the feeling of nationality grew stronger and stronger, until, when secession came, Horace Greeley’s statement that “the right to secede may be a revolutionary one, but it exists nevertheless,” found scarcely any support in public opinion.

Many reasons have been assigned for this divergence. Two causes for the drift of opinion in the North suggest themselves at once: the development in the Northwest of vigorous new states which had no independent existence before they became members of the Union, and the increasing number of immigrants in whose minds there were no strong associations or traditions connected with any state. In addition to these might be mentioned the fact that economic development in the North had known no state lines, and growing prosperity had given birth to a sense of national pride and national enthusiasm. In the South these influences had been less felt, there had been little reason for any increase in national feeling, and political theories had, with social and economic conditions, suffered little change. Moreover, when the South saw what it believed to be its rights seriously threatened by the other sections through the National government, it searched more eagerly for whatever legal defence might fairly be found against Federal aggression.

So general did the belief in state sovereignty become throughout the South that the chief question in regard to secession in 1860 and 1861 was, not whether it was a legal right, but whether the acts of the Northern states and the election of Lincoln justified it as a matter of general fairness and good faith toward the other states and as a matter of practical wisdom. In this sense its justification was found in the failure of the Northern states to keep the compact and in the aggressively anti-slavery attitude of the Republican party.

The determination of the National government to use force against the seceding states gave rise to the last phase of the doctrine of secession. The doctrine that a state had the right to secede implied of course that no one had a legal right to use force to prevent it. But some who doubted the right of secession believed, with Buchanan, that there was no authority given by the constitution for the use of force against a state. Others, like Lincoln, held strongly to the national view of our government and believed it a right and a duty to put down what they considered rebellion. Under these circumstances war was inevitable.