I.

THE name First given to the territory occupied by the present United States was Virginia. It was bestowed upon the Country by Elizabeth, greatest of English queens. The United States of America are mere words of description. They are not a name. The rightful and historic name of this great Republic is “Virginia.” We must get back to it, if the Country’s name is to have any real significance.

II.

Virginia was the First colony of Great Britain, and her successful settlement furnished the inspiration to English colonization everywhere. For it was the wise Lord Bacon who said that, “As in the arts and sciences the ‘first invention’ is of more consequence than all the improvements afterwards, so in kingdoms or plantations, the first foundation or plantation is of more dignity than all that followeth.”

III.

On May 13, 1607, the pioneers brought over by the Sarah Constant, the Good Speed, and the Discovery arrived at Jamestown on James River, and Founded the Republic of the United States based on English conceptions of Justice and Liberty. The story of this little settlement is the story of a great nation expanding from small beginnings into one of more than 100,000,000 people inhabiting a land reaching finally from ocean to ocean and abounding in riches and power, till when the liberties of all mankind were endangered the descendants of the old Jamestown settlers did in their turn cross the ocean and helped to save the land from which their fathers came.

IV.

Before any other English settlement was made on this continent, democracy was born at Jamestown by the establishment of England’s free institutions—Jury trial, courts for the administration of justice, popular elections in which all the “inhabitants” took part, and a representative Assembly which met at Jamestown, July 30, 1619, and digested the first laws for the new commonwealth.

V.

There at Jamestown and on James River was the cradle of the Union—The first church, the first blockhouse, the first wharf, the first glass factory, the first windmill, the first iron works, the first silk worms reared, the first wheat and tobacco raised, the first peaches grown, the first brick house, the first State house, and the first free school (that of Benjamin Syms, 1635).

VI.

In Virginia was the First assertion on this continent of the indissoluble connection of representation and taxation.

In 1624 a law was passed inhibiting the governors from laying any taxes on the people without the consent of the General Assembly, and this law was reenacted several times afterwards. In 1635 when Sir John Harvey refused to send to England a petition against the King’s proposed monopoly of tobacco, which would have imposed an arbitrary tax, the people deposed him from the government and sent him back to England, an act without precedent in America. In 1652 when the people feared that Parliament would deprive them of that liberty they had enjoyed under King Charles I, they resisted, and would only submit when the Parliamentary Commissioners signed a writing guaranteeing to them all the rights of a self-governing dominion. And when after the restoration of King Charles II. the country was outraged by extensive grants of land to certain court favorites, the agents of Virginia, in an effort to obtain a charter to avoid these grants, made the finest argument in 1674 for the right of self-taxation to be found in the annals of the 17th century. Claiborne’s Rebellion and Bacon’s Rebellion prove that Virginia was always a Land of Liberty.

During the 18th century the royal governors often reproached the people for their “Republican Spirit,” until on May 29, 1765, the reproach received a dramatic interpretation by Patrick Henry, arousing a whole continent to resistance against the Stamp Act.

VII.

Virginia Founded New England. In 1613 a Virginia Governor, Sir Thomas Gates, drove the French away from Maine and Nova Scotia and saved to English colonization the shores of Massachusetts and Connecticut. In 1620 the Pilgrim Fathers were inspired to go to North America by the successful settlement at Jamestown. They sailed under a patent given them by the Virginia Company of London, and it was only the accident of a storm that caused them to settle outside of the limits of the territory of the London Company, though still in Virginia. The Mayflower compact, under which the 41 emigrants united themselves at Cape Cod followed pretty nearly the terms of the original Virginia Company’s patent.

In 1622 the people at Plymouth were saved from starvation by the opportune arrival of two ships from Jamestown, which divided their provisions with them. Without this help the Plymouth settlement would have been abandoned.

The 41 Pilgrim Fathers established an aristocracy or oligarchy at Plymouth, for they constituted an exclusive body and only cautiously admitted any newcomers to partnership with them in authority. As time went on, the great body of the people had nothing to say as to taxes or government.

Citizenship at Plymouth and in all New England was a matter of special selection in the case of each individual. The terms of the magistrates were made permanent by a law affording them “precedency of all others in nomination on the election day.” The towns of New England were little oligarchies, not democracies. It was different in Virginia. There the House of Burgesses, which was the great controlling body, rested for more than a hundred years upon what was practically universal suffrage (1619-1736), and even after 1736 many more people voted in Virginia than in Massachusetts. There was a splendid and spectacular body of aristocrats in Virginia, but they had nothing like the power and prestige of the New England preachers and magistrates.

“By no stretch of the imagination,” says Dr. Charles M. Andrews, Professor of History in Yale University, “can the political condition in any of the New England Colonies be called popular or democratic. Government was in the hands of a very few men.”

VIII.

Virginia led in all the measures that established the independence of the United States. Beginning with the French and Indian War, out of which sprang the taxation measures that subsequently provoked the American Revolution, Virginia under Washington, struck the first blow against the French, and Virginian blood was the first American blood to flow in that war. Then, when, after the war, the British Parliament proposed to tax America by the Stamp Act, it was the Colony of Virginia that rang “the alarm bell” and rallied all the other colonies against the measure by the celebrated resolutions of Patrick Henry, May 29, 1765, which brought about its repeal.

Later when the British Parliament revived its policy of taxation in 1767 by the Revenue Act, though circumstances made the occasion for the first movements elsewhere, it was always Virginia that by some resolute and determined action of leadership solved the crisis that arose.

There were four of these crises:

(1) The first occurred when Massachusetts, by her protest, in 1768, against the Revenue Act, stirred up Parliament to demand that her patriot leaders be sent to England for trial. Massachusetts was left quite alone and she remained quiescent. Virginia stepped to the front and by her ringing resolutions of May 16, 1769, aroused the whole continent to resistance, which forced Parliament to compromise, leave the Massachusetts men alone, and repeal all the taxes except a small one on tea. After the Assembly, “The Brave Virginians” was the common toast throughout New England.

(2) The next crisis occurred in 1772. In that year the occasion for action occurred in the smallest of the colonies, Rhode Island, by an attack of some unauthorized persons on the sloop Gaspee, which was engaged in suppressing smuggling. The King imitated Parliament by trying to renew the policy of transporting Americans to England for trial, but Virginia caused the King and his Counsellors to desist from their purpose by her system of inter-colonial committees, which brought about a real continental union of the colonies for the first time.

(3) The third crisis occurred in 1774, after a mob of disguised persons threw the tea overboard in Boston harbor. Though Boston did not authorize this proceeding, Parliament held her responsible and shut up her port. Virginia thought this unjust, and was the first colony to declare her sympathy with Boston, and the first, in any representative character for an entire colony, to call for a Congress of all the colonies.

And to that Congress which met September 5, 1774, she furnished the first president, Peyton Randolph, and the greatest orators, Patrick Henry and Richard Henry Lee.

The remedy proposed by this Congress was a plan of non-intercourse already adopted in Virginia, to be enforced by committees appointed in every county, city and town in America.

(4) The fourth crisis began in 1775 with the laws passed by the British Parliament to cut off the trade of the colonies, intended as retaliatory to the American non-intercourse. This led to hostilities, and for a year, during which time the war was waged in New England, the colonists held the attitude of confessed rebels, fighting their sovereign and yet professing allegiance to him. When the war was transferred to the South with the burning of Norfolk and the battle of Moore’s Creek Bridge, this attitude became intolerable to the Southerners, and they sought for a solution of the difficulty in Independence.

While Boston was professing through her town meeting her willingness “to wait, most patiently to wait” for Congress to act, and the Assembly of the Province deferred action till the towns were heard from, it was North Carolina, largely settled by Virginians, that on April 12, 1776, instructed her delegates in Congress to concur with the delegates from the other Colonies in declaring independence, and it was Virginia that on May 15, 1776, commanded her delegates to propose independence. The first explicit and direct instructions for independence anywhere in the United States were given by Cumberland County, in Virginia, April 22, 1776. Unlike the tumultuary, unauthorized, and accidental nature of the leading revolutionary incidents in New England, such as the Boston Tea Party and the Battle of Lexington, the proceedings in Virginia were always the authoritative and official acts of the Colony.

All the world should know that it was Richard Henry Lee. a Virginian, who drew the resolutions for independence adopted by Congress July 2, 1776, and that it was Thomas Jefferson, a Virginian, who wrote “the Declaration of Independence” adopted July 4, 1776, a paper styled by a well known New England writer as “the most commanding and most pathetic utterance in any age of national grievances and national purposes.”

IX.

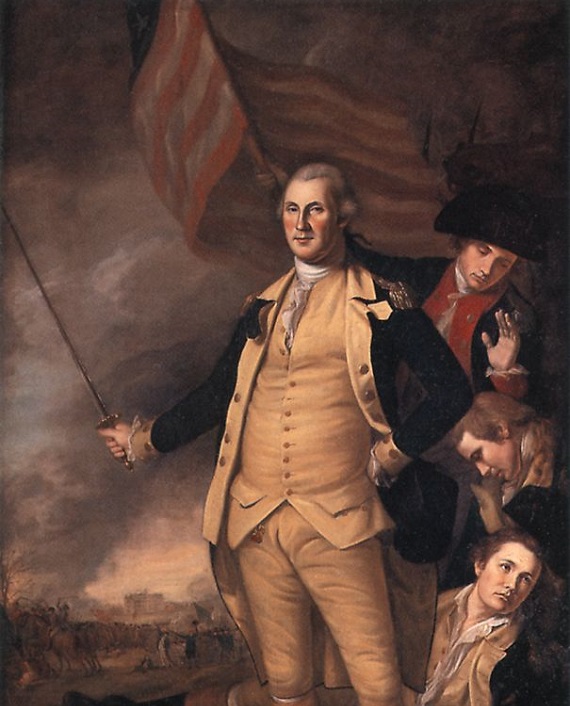

During the war that ensued Virginia contributed to the war what all must allow was the soul of the war—the immortal George Washington, whose immense moral personality accomplished more in bringing success than all the money employed and all the armies placed in the field; and the war had its ending at Yorktown, only a few miles from the original settlement at Jamestown. The Father of this great Republic was a Virginian.

X.

Virginia led in the work of organizing the Government of the United States. She called the Annapolis Convention in 1786, and furnished to the Federal Convention at Philadelphia which met, as the result of this action, its chief constructor — James Madison—who has been aptly described as Father of the Constitution. She furnished the two greatest rival interpreters of its powers, Thomas Jefferson and John Marshall, and gave the Union its first President, George Washington.

XI.

Virginia, through her explorers, generals and presidents, made the Union a continental power.

It was Patrick Henry and George Rogers Clark who effected the conquest of the Northwest Territory, which eventually added five great States to the Union. Meriwether Lewis and William Clark made the first thorough exploration of the West. And Louisiana, Florida and Texas were added to the Union by Virginia Presidents—Jefferson, Monroe, and Tyler. Nor can it be forgotten that all the far West was the result of the annexation of Texas by Tyler, indirectly leading to the Mexican War, whose success was assured by two Virginia generals—Zachary Taylor and Winfield Scott.

Had the New England influences, which were opposed to the Annexation policy, dominated, the United States to-day, if it existed at all, would be confined to a narrow slip along the Atlantic shore.

XII.

A Virginia President, James Monroe, gave to the world over his name the Monroe Doctrine, which has regulated, to the present day, the relations of America to the nations of Europe and the rest of mankind. “America for Americans,” he said in substance.

XIII.

Virginians created those ideals for which the Republic of the United States stands to-day—democracy, religious freedom, and education.

Democracy: Not only did Virginia have the first legislative Assembly, which rested for more than a hundred years on universal suffrage, she was the headquarters, after the American Revolution, of the great Democratic-Republican party, under the leadership of Thomas Jefferson. This party was the champion of the popular idea against the aristocratic notions of the Federalists, who had their headquarters in New England. By completely destroying the Federalist party Virginia sowed the seeds of democracy throughout the United States, and the world. All political parties in the United States since that time have the same creed as to the equality of the citizen. Thomas Jefferson is incomparably the greatest living influence in America. He is, in fact, the Founder of Americanism, as we understand it.

Through an act, of which the same great man was the author, Virginia was the first State in the world to impose a penalty for engaging in the slave trade (1778), and in the Federal Convention in 1787 her delegates bitterly opposed the provision in the Constitution supported by the Puritan delegates from New England, permitting the slave trade for twenty years. New England men were great shippers of slaves.

Religious Freedom: After the same manner Virginia sowed the seeds of religious freedom. All New England, except Rhode Island, in Colonial days, was principled against religious liberty. Even after the American Revolution the preachers and a group of laymen in each community grasped all power and the people were forced into submission. In 1793 only one in twenty of the people in Connecticut exercised the right of suffrage. Even in Rhode Island there were, till a late date, laws against Roman Catholics voting or holding office, and it took Dorr’s Rebellion in 1842 to break up the restrictions on the ballot handed down from Colonial days.

The persecuting spirit was not absent in Virginia, but it was never so severe or relentless as in New England. And for many years before the American Revolution there were no religious qualifications for voting or holding office.

The Declaration of Rights of Virginia, drawn by George Mason in 1776, and imitated by all the other States, placed the principle of religious freedom, for the first time, upon a truly philosophic basis. Virginia was then the First State in the world to proclaim absolute equality and freedom of religion to the people of all faiths—Christians, Jews, Mohammedans, etc. The principle enunciated by Mason was enacted into law by Thomas Jefferson, whose bill for Religious Freedom in 1785 invested conscience with the wings of heaven.

Education: Finally, it was a Virginian, Thomas Jefferson, that furnished the ideals of popular education. The system of schools as they existed in Massachusetts in Colonial days did not remotely resemble the present ideal. As a system they were under no central authority, were not free to the scholar who had to pay for tuition, and were primarily directed to the maintenance and upholding of the Congregational Church. None but members of that Church could be teachers in Massachusetts. In practice, the towns neglected their responsibilities “shamelessly,” and a large percentage of the people could neither read nor write.

Virginia did not go far in her educational system, but in her ancient laws for educating poor children, and establishing and financing William and Mary College, the colony clearly recognized education as a public function. As to the general supply of education, however, the Colony had by far the best libraries and teachers and, according to Mr. Jefferson, the mass of education, accomplished through tutors and private schools, “placed her among the foremost of her sister States,” at the time of the Revolution. But it was the great bill of Thomas Jefferson in 1779, correlating the different gradations of schools — beginning with the primary schools and ending with the University, that furnished the real ideal on which the public school system of the United States rests to-day.

XIV.

Before 1861 the Union consisted practically of two nations separated by Mason and Dixon’s line, differing in habits of thought, customs, and largely in institutions. It was only the pressure of British taxation that brought these two nations together, and immediately after the peace in 1783 the separative forces began to exert themselves. They were first sharply manifested in New England, where plans of secession were discussed as early as 1800. So far did this spirit proceed that in 1812-1814 the New England States professed the extreme doctrine of States rights, and did all they could to paralyze the arm of the Federal Government during the course of a war with the greatest power in Europe. As late as 1844 the Massachusetts Legislature, after declaring that “uniting an independent foreign state” (like Texas) “with the United States was riot among the powers delegated to the General Government,” stated its resolve to be “to submit to undelegated powers in no body of men on earth,” and in 1845 it announced the doctrine of nullification by declaring that the admission of Texa? “would have no binding force whatever on the people of Massachusetts.”

But by this time the great increase in the wealth and population of the North, chiefly due to the foreign immigration, caused New England to abandon the separative policy and substitute that of nationality to be preserved by force. The South now being the weaker section was compelled into the opposite policy, and finally, obeying the dictates of its economic and social forces, seceded from the Union and organized a separate government.

Virginia, who had a sentimental attachment to the Union, attempted to preserve it by the Peace Conference, but finding that impossible, and placed in a dilemma of fighting the northern Union or fighting the Southern Confederacy, she allied herself with the latter, of which she was really an integral part. In the light of the doctrine of self determination, now so generally admitted, it appears one of the most astonishing things in history that eight millions of people, occupying a territory half the size of Europe, with a thoroughly organized government, and capable of fighting one of the greatest wars on record, were not permitted to set up for themselves.

By the results of the war, one of the two nations of the old Union was wiped out and incorporated into the other. But Virginia was the capital of the Southern Confederacy and the battlefield of the war, and the veterans of Virginia and the South have lived to see the principle of self government and self determination for which they fought accepted by the world at large.

In the war for Southern Independence, as in the American Revolution, Virginia furnished the Ideal Man. In one war it was George Washington, and in the other it was Robert E. Lee. Both these great men were distinguished by the union of a handsome person with a supremely majestic soul, brave, refined, dignified and clean. They were, indeed, kingly men.

XV.

The contributions of Virginia to science should not be passed by in this summary of her priorities. Among the creators of an epoch the following may be mentioned particularly. James Rumsey first demonstrated in her waters in 1786 the possibilities of steam as applied to a river boat. Cyrus Hall McCormick revolutionized agriculture throughout the world by his invention of the reaper. Matthew Fontaine Maury about the same time did the same thing for ocean navigation. He furnished the plans for the laying of the Atlantic Cable, and was the father of the modern science of torpedo and mine laying. In recent days Walter Reed, of Gloucester County, was foremost in discovering the cause of yellow fever and rendering that dread disease innocuous.

During the war for Southern Independence, it was the ironclad Virginia (or Merrimac), constructed by two master engineers, John L. Porter, of Portsmouth, Va., and John Mercer Brooke, of Lexington, Va., that showed in an epoch making battle fought in Hampton Roads, March 8, 1862, with the Federal wooden battleships, the superiority of iron ships over wooden ones, no matter how gallantly manned and bravely fought.

Then and there Virginia genius and invention Founded the present navies of the world.

The Monitor, which engaged the Virginia the next day (March 9, 1862), had no share in this glory. Naval warfare would have been revolutionized if it had never showed up. The battle of the ninth is only interesting as it affords a test of the prowess of the two vessels. The Monitor was driven from the field, and ever after avoided conflict with the Virginia, though repeatedly challenged in Hampton Roads to a new trial of strength.

One Comment