The dogs of racial war were released this May in Minneapolis by the senseless death of George Floyd, a black man, under the knee of Derek Chauvin, a white police officer. Even though Chauvin had a long record of misconduct, the charges against him had been mainly disregarded by the local authorities, including former prosecutor, now Senator and failed Democratic presidential candidate, Amy Klobuchar. While the initial protests against this outrage and the rising cries of black lives matter was certainly justified, the ensuing mob violence under the politicized banner of “Black Lives Matter” (“BLM”) has become quite another matter entirely . . . one that threatens the very foundation of the country. What began as a cry for simple justice in Minnesota has now turned into a nationwide movement of mass mayhem and destruction in which the ghosts of such long dead issues as Southern secession and slavery have been called forth to justify the Orwellian erasure and rewriting of America’s history and heritage. Now, a third ghost has been resurrected from its quiet grave . . . the issue of white slaves in colonial America.

The story of white enslavement in the American colonies is now being portrayed by the BLM radicals as nothing more than a recently created myth by white supremacists and Neo-Confederates designed to lead the public off the path to Black social justice. Their claim has won the strong support of the New York Times and such organizations as the Southern Poverty Law Center which would have the public believe that the story is merely a revisionist attack on “BLM” by “racist trolls.” The truth is that historical accounts of the enslavement of large numbers of white Europeans in the British colonies of both North and Central America go back over a hundred years and have been well documented in a number of works by noted historians.

Perhaps the earliest account of this matter appeared only fifty years after the end of slavery in the United States in a 1915 tract written by the Irish socialist labor leader James Connolly. In this work, Connolly cites that during the British Commonwealth period from 1649 to 1660 tens of thousands of Irish men, women and children were taken by the English military to be shipped to the British West Indies as slaves. One such instance was described in great detail by Connolly who wrote that an English captain named John Vernon and a civilian contractor named David Sellick were directed by Cromwell’s Commissioners to round up two hundred fifty Irish women between the ages of twelve and forty-five and three hundred men aged between twelve and fifty from both Youghal and Kinsale in County Cork, as well as some from the counties of Waterford and Wexford. They were then to be taken to a shipping firm in Bristol, England, for transport to the Americas as slaves. In all, that British firm was reported to have shipped almost seven thousand Irish slaves to the British colonies. Connolly added that most of these Irish captives were branded in order that they could be more easily recognized if they escaped their enslavement.

In the United States, one of the earliest accounts of white slaves was in the 1929 book “Life and Labor in the Old South” by Dr. Ulrich Bonnell Phillips of LaGrange, Georgia. Dr. Phillips graduated with an MA from the University of Georgia and attained his doctorate at Columbia University in New York. He also taught at the University of Wisconsin, Tulane University and Yale from 1902 until his death in 1934. Phillips was a highly regarded academic whose primary interest was the social and economic history of the antebellum South and slavery . . . fields he largely dominated in his time. He was convinced that Southern slavery was becoming unprofitable, had reached its geographic limits by 1860 and would have come to a natural end without a war . . . a conflict he thought was completely needless. Phillips’ exhaustive research also led him to the conclusion that black slaves were generally not mistreated and that they had been provided with adequate food, clothing, housing and medical attention. His research methodology was a model for scholars in that field for decades, even those who might disagree with some of his conclusions on the treatment of black slaves, and he is still considered to be one of the most influential authorities on the antebellum South.

In his seminal work on Southern slavery, Phillips also called attention to the earlier use of white slaves in the Virginia Colony and how their enslavement set a crucial pattern for the black African slavery that was to come. His studies revealed that the system established for white slaves largely controlled, governed and organized the later system for black slaves who he said were “late comers who fitted into a system already developed.” His book also cited a statement made in 1619 by John Pory, then the secretary of Governor Sir George Yeardley and later the first speaker of the Virginia Assembly, in which Pory said that “white slaves are our principle wealth.” Phillips’ account of white slaves in America was not challenged at the time, and remained so for more than eighty years.

The issue of white slaves in the South was also touched on by another well respected authority of that day, Dr. Lewis Cecil Gray, in his massive 1933 work “History of Agriculture in the Southern United States to 1860.” Gray was born in Missouri but received his doctorate from the University of Wisconsin where he later became a professor of economics. In 1919, he was appointed as the head economist at the United States Bureau of Agricultural Economics and later held a number of other high Federal positions in the administrations of Presidents Wilson, Harding, Coolidge and Roosevelt. In his 1933 study, Gray wrote about Sir George Sandys’ 1618 plan for the Virginia Colony in which Sandys proposed that the white workers then being held in bondage to the Treasurer’s Office of the Colony should “belong to said office forever” and that the “service of whites bound to the Berkeley Hundred be deemed perpetual.”

The matter of white slaves in America was again raised four decades later in 1975 by Massachusetts historian and historical author Clifford Lindsey Anderman in his book “Colonists for Sale: The Story of Indentured Servants in America.” Anderman’s well documented book presented numerous examples of white men and women of various nationalities who came to the Americas in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries as indentured workers and servants. These people sold themselves to their American masters, usually with a written contract, to obtain their passage and then, in theory, work without wages for an agreed upon number of years. Others known as redemptioners made no such prior agreement, and had to negotiate the terms of their servitude after their arrival . . . with many of the latter becoming actual slaves for life. Many of the indentured workers also found themselves serving terms far longer than in their contracts . . . or even for life as punishment for various infractions dictated by their masters. In some cases, such matters were brought to court where sentences of servitude “durante vite,” during life, were often handed down, The book also cites many documented cases where white Europeans, including Irish, Scots and Germans were either kidnapped and forced to sign a contract or were tricked into indentures, then imprisoned under inhuman conditions and horribly mistreated.

Thirty-five years later, the issue of Irish slavery was again brought up by a prolific Japanese-American writer of Southern history, Rhetts Akamatsu of Marietta, Georgia. Akamatsu’s 2010 book, “The Irish Slaves: Slavery, Indenture and Contract Labor Among Irish Immigrants,” was followed two years later by Dee Masterson’s “White Slavery in Colonial America” which cited an effort to suppress the two hundred-year history of white slaves in America. The Chicago author wrote of the thousands of white men, women and children who were transported to British America, many in chains, to work as indentured servants and laborers. Masterson also felt that the term “indentured,” in reality, actually meant slave, as not only were a vast number of the so-called contracts signed under duress or false pretensions, but many of the workers either died before the end of their contract period or, as punishment, had their period of servitude greatly extended . . . even for life. Masterson concluded that, contrary to accepted history, colonial America was not built exclusively on the backs of black African slaves, but also on those of the white slaves that preceded and then later coexisted with them.

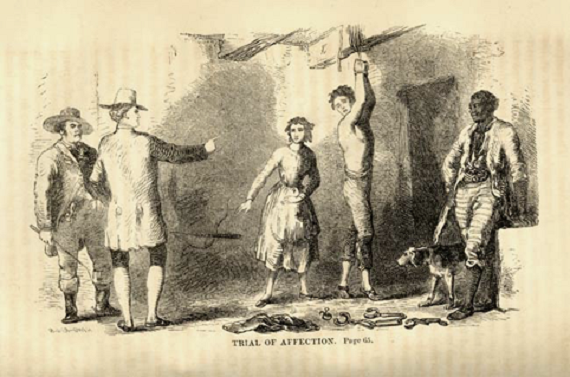

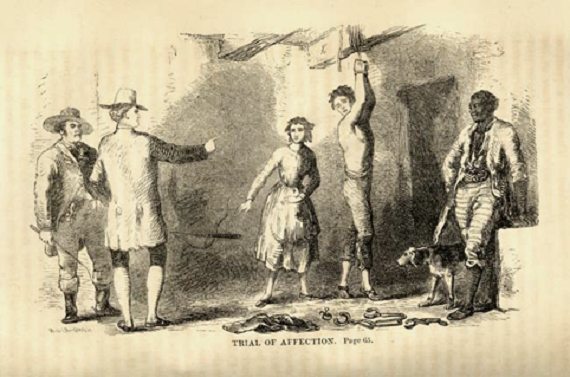

Then, in 2017, TV producer and director Don Johnson and journalist Michael Walsh co-authored another well-documented study published by the New York University Press entitled “White Cargo: The Forgotten History of Britain’s White Slaves in America.” This work expanded the subject of white slaves in the British colonies of North America to include those in the British West Indies which the “Times of London” called an “eye opening and heart-rending story.” The book investigated white slavery, mainly Irish and Scottish, in the British colonies during the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries and again showed that indentured servitude, rather than being benignly paternalistic, was actually little more than true slavery, with such people being sold at auction, chained, imprisoned and brutally punished for any form of disobedience. The writers cited that they found contemporary accounts of such white slaves being hung by their hands for hours, some with their feet set on fire or being completely burned alive, then decapitated and their heads placed on pikes as a warning to others not to break the rules.

The writers of “White Cargo” also found that by the middle of the Seventeenth Century, the primary source of British slaves was Ireland and that on the Caribbean island of Monserrat, more than half the total population were Irish slaves. Much of the same was the case on other island colonies in the British West Indies, such as Antigua, Barbados, Jamaica and St, Kitts and Nevis. According to British State Papers of 1701 for Colonial America and the West Indies, plantation slavery in the West Indies began in 1627 on Barbados and by 1640 there were twenty-five thousand slaves on the island, with almost twenty-two thousand of those being white. Reminders of the Irish slave heritage can still be found on some of the Caribbean islands, such as Irish Town and Dublin Castle in Jamaica’s Saint Andrew Parish, Clonmel and Kildare in Saint Mary’s Parish and Belfast and Middleton in Saint Thomas Parish. Many Irish family names also have a centuries-old heritage on a number of the islands.

Over a century of academic research and writing on the subject has amply proven the existence of white slaves being a fact of life for more than two hundred years in Great Britain’s American Colonies. In spite of this, any reference to such history today is being portrayed by those in the BLM movement and their cohorts in the media and elsewhere as nothing more than a recent racist myth. They would have you now believe, as put forth in the New York Times “1619” series, that the first and only slaves in America were black Africans. If you were to accept this specious BLM argument as true history and deny the overwhelming wealth of evidence to the contrary . . . then the adage on the acceptance of a lie being told often enough would once again prove to be the case.