This speech was delivered before the annual meeting of the Georgia Bar Association at Tybee Island on June 2, 3, and 4, 1927.

Mr. PRESIDENT and gentlemen of the Georgia Bar Association: I make no apology for presenting to you today as the subject of my address a technical and abstruse question, be cause it involves the foundation stone of our form of Government.

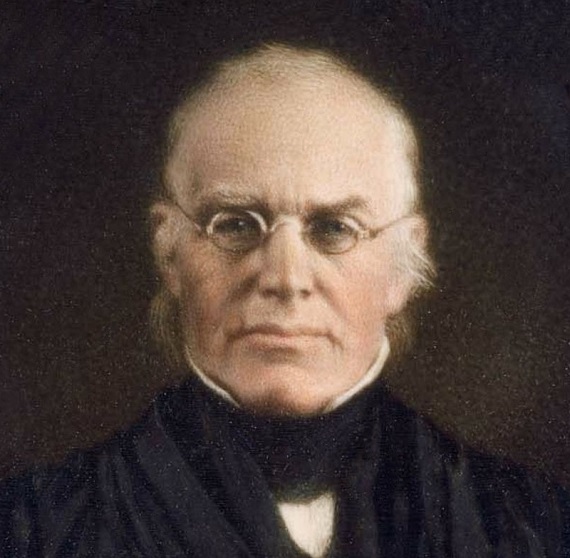

The subject to which I invite your attention may be put in this form, “Judge Story’s position on the so-called General Welfare Clause of the Constitution of the United States.”

The words “the general welfare” are to be found in two places in the Constitution—in the preamble thereto and in Article 1, section 8, clause 1. All reputable writers concur in the statement that the words of the preamble to the Constitution constitute no grants of power, and therefore our investigation is confined to the words as found in Article 1, section 8, clause 1. which reads,

“The Congress shall have power lo lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts and excises, to pay the debts and provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States but all duties, imposts, and excises shall be uniform throughout the United States.”

It will be observed by reading the whole section carefully that the above clause is the first of eighteen clauses, placed consecutively one after another, separated by a semicolon from each other, each beginning with the word “To” with a capital “T,” and all eighteen clauses constituting one sentence, the last clause of which is not a separate grant of power like the others, but is intended to perfect and enlarge the previous seventeen grants of power to Congress. It is known as the coefficient clause, and reads:

(The Congress shall have power) “To make all laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into execution the foregoing powers, and all other powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States, or in any Department or Officer thereof.”

To a proper understanding of the question it is proper to examine the propositions suggested in the Constitutional Convention on the subject of the powers of Congress.

Mr. Hamilton’s plan on the powers of Congress provided that the Legislature of the United States should have “powers to pass all laws whatsoever subject to the negative hereafter mentioned,” which negative was the power of the Executive to have a negative on all laws about to be passed.

Mr. Randolph’s plan proposed Congress should have all powers which it possessed under the Confederation “and moreover to legislate in all cases to which the separate States are incompetent, or in which the harmony of the United States may be interrupted by the exercise of individual legislation,” etc.

Mr. Patterson’s plan provided that Congress should have all powers which it possessed under the Confederation and power “to pass acts for raising a revenue, by levying a duty or duties on all goods, etc., imported into any part of the United States, etc., and by postage on all letters….to be applied to such Federal purposes as they shall deem proper and expedient, to pass acts for the regulation of trade and commerce as well as with foreign nations as with each other,” etc.

Mr. Pinckney’s plan, offered on the 29th of May, 1787, three days after the Convention met, provided, “The Legislature of the United States shall have power to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts and excises; “To regulate commerce; etc. “To borrow money; etc. “To establish post offices ;” containing in all twenty-one specific grants of power, the last of which reads, “and to make all laws for carrying the foregoing powers into execution.”

Pinckney’s plan, as introduced, on this subject came out of the Convention on the 15th of September in form and substance pretty much as it was introduced on the 29th of May, with this change, that on the 4th of September there was added to clause 1, after the word “excises” the words “to pay the debts and provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States.”

Hamilton’s fight in the Convention was to give to Congress unlimited power. Pinckney’s plan prescribed definite powers to Congress. This was the struggle of the Convention, and while Hamilton’s plan, on this clause, was practically voted down six times in the Convention, either directly or by voting up a distinct opposing proposition, his followers have struggled to show that the words “the general welfare” put into clause 1, section 8, Article 1. really mean what was specifically rejected by the Convention six times. (See speech of Henry St. George Tucker -Maternity Bill—delivered in House of Representatives March 3, 1926, page 15 et seq.)

I

Judge Story’s position on this subject can best be seen from quoting his own words on the subject, beginning at Sec. 906 of his Commentaries, page 628, Vol, 1:

“Sec. 906. The first clause of the eighth section is in the following words ‘The congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts, and excises, to pay the debts rind provide for the common defense, and general welfare of the United States; but all duties, imposts, and excises, shall he uniform throughout the United States.’

“Sec, 907. Before proceeding to consider the nature and extent of the power conferred by this , and the reasons, on which it is founded, it seems necessary to settle the grammatical construction of the clause, and to ascertain its true meaning. Do the words, ‘to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts, and excises,’ constitute a distinct, substantial power; and the words, ‘to pay the debts arid provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States,’ constitute another distinct and substantial power? Or are the latter words connected with the former, so as to constitute a qualification upon them? This has been a topic of political controversy and has furnished abundant materials for popular declamation and alarm. If the former be the true interpretation, then it is obvious, that under the color of the generality of the words to ‘provide for the common defense and general welfare,’ the government of the United States is, in reality, a government of general and unlimited powers, notwithstanding the subsequent enumeration of specific powers: if the latter be the true construction, then the power of taxation only is given by the clause, and it is limited to objects of a national character, ‘to pay thr debts and provide for the common defense and the general welfare.’ But see e Contra, §923.

“Sec 908. The former opinion has been maintained by some of great ingenuity, and liberality of views. The latter has been the generally received sense of the nation, and seems supported by reasoning at once solid and impregnable. The reading, therefore, which will be maintained in these commentaries, is that, which makes the latter words a qualification of the former; and this will be best illustrated by supplying the words, which are necessarily to be understood in this interpretation. They will then stand thus: ‘The Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts, and excises, in order to pay the debts, and to provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States;’ that is, for the purpose of paying the public debts, and providing for the common defense and general welfare of the United States. In this sense, Congress has not an unlimited power of taxation: but it is limited to specific objects,—the payment of the public debts, and providing for the common defense and general welfare. A tax. therefore, laid by congress for neither of these objects would be unconstitutional, as an excess of its legislative authority. In what manner this is to be ascertained, or decided, will be considered hereafter. At present the interpretation of the words only is before us; and the reasoning, by which that already suggested has been vindicated, will now be reviewed.

“Sec. 909. The constitution was, from its very origin, contemplated to be a frame of a national government, of special and enumerated powers, and not general and unlimited powers. This is apparent, as will be presently seen, from the history of the proceedings of the convention, which framed it; and it has formed the admitted basis of all legislative and judicial reasoning upon it; ever since it was put into operation, by all, who have been its open friends and advocates, as well as by all, who have been its enemies and opponents. If the clause, ‘to pay the debts and provide for the common defence and general welfare of the United States,’ is construed to be an independent and substantive grant of power, it not only renders wholly unimportant and unnecessary the subsequent enumeration of specific powers; but it plainly extends far beyond them, and creates a general authority in congress to pass all laws, which they may deem for use common defense or general welfare. Under such circumstances, the constitution would practically create an unlimited national government. The enumerated powers would tend to embarrassment and confusion: since they would only give rise to doubts, as to the true extent of the general power, or of the enumerated powers.

“Sec. 910. One of the must common maxims of interpretation is (as has already been stated), that, as an exception strengthens the force of a law in cases not excepted, so enumeration weakens it in cases not enumerated. But, how could it be applied with success to the interpretation of the constitution of the United States, if the enumerated powers were neither exceptions from, nor additions to, the general power to provide for the common defence and general welfare? To give the enumeration of the specific powers any sensible place or operation in the constitution, it is indispensable to construe them, as not wholly and necessarily embraced in the general power. The common principles of interpretation would seem to instruct us, that the different parts of the same instrument ought to be so expounded as to give meaning to every part which will bear it. Shall one part of the same sentence be excluded altogether from a share in the meaning; and shall the more doubtful and indefinite terms be retained in their full extent, and the clear and precise expressions be denied any signification? For what purpose could the enumeration of particular powers be inserted, if these and all others were meant to be included in the preceding general power ? Nothing is more natural or common than first to use a general phrase, and then to qualify it by a recital of particulars. But the idea of an enumeration of particulars which neither explain nor qualify the general meaning, and can have no other effect than to confound and mislead, is an absurdity, which no one ought to charge on the enlightened authors of the constitution. It would be to charge them either with premediated folly or premediated fraud.

“Sec. 911. On the other hand, construing this clause in connection with, and as a part of the preceding clause, giving the power to lay taxes, it becomes sensible and operative. It becomes a qualification of that clause, and limits the taxing powers to objects for the common defense or general welfare. It then contains no grant of any power whatsoever; but it is a mere expression of the ends and purposes to be effected by the preceding power of taxation.”

II

The argument of Judge Story (contained in sections 909 and 910) which demolishes the theory of the Hamiltonians, shows conclusively that the words “the common defense and general welfare,” as found in this section, constitute no substantive grant of power; and he further denies that these words contain any power whatsoever. His argument is irresistible in its conclusion to any unbiased mind, but it furnishes an equally powerful argument against his claim that the words “to provide for the common defense and general welfare” are merely words of limitation on the taxing power, for his argument for the latter claim is based upon the relationship of those words solely to the first clause of section 8, and excludes their relationship to the other seventeen distinct clauses in that sentence. He would thus exclude these words “common defense and general welfare” from any participation in the construction of the whole sentence. How can that consist with his language in sections 909 and 910?

“Sec. 910. . . . The common principles of interpretation would seem to instruct us that the different parts of the same instrument ought to be so expounded, as to give meaning to every part, which will bear it. Shall one part of the same sentence be excluded altogether from a share in the meaning: and shall the more doubtful and indefinite terms be retained in their full extent, and the clear and precise expressions be denied ally significance?”

And yet, to maintain his argument, the doubtful and indefinite terms “common defense and general welfare” are allowed to stand unconnected, unchallenged and unaffected by the clear and precise expressions which follow. Or how can his argument be maintained against the declaration in section 910?

“Nothing is more natural or common than first to use a general phrase, and then to qualify it by a recital of particulars.”

If this expression controlled Judge Story in demolishing the Hamiltonian claim of a substantive power in the words “common defense and general welfare,” why should not this same expression of his, on like principle, apply in the attempt to make them merely words of limitation on the taxing power? for this last quotation from Judge Story, section 910, shows that there is an indissoluble bond of dependence, that cannot be broken, between the general expression “common defense and general welfare” and the subsequent explicit grants of power contained in the same sentence in section 8. The subsequent enumerated powers were sufficient to convince the learned Judge that these genera; and indefinite terms could not be regarded as absorbing or nullifying the specifically enumerated grants. But by taking the two together, and giving to each that meaning which a just and reasonable construction justifies, he destroys the Hamiltonian argument; but alas! it is fatal to his argument holding these words to be merely words of limitation, for in it he rejects the basic foundation of his former argument. His argument showing that the Hamiltonian claim, that these words “common defense and general welfare” constituted a substantive grant of power, was based chiefly on the grammatical construction of the whole sentence, and he invoked two principles that must be admitted by all as sound, which have been quoted in sections 909 and 910; the first that the different parts of the same sentence ought to be so expounded as to give meaning to every part which will bear it, and, with striking emphasis, he asks a question which can be answered only in one way,

“Shall one part of the same sentence be excluded altogether from a share in the meaning; and shall the more doubtful and indefinite terms be retained in their full extent, and the clear and precise expressions be denied any signification?”

and, second, a principle recognized by all authors and writers,

“That nothing is more natural or common than first to use a general phrase, and then to qualify it by a recital of particulars.”

These are two principles general in their application to all sentences and a fortiori when applied to one sentence, must be followed in the different construction of the same sentence; but this, Judge Story does not do, but rejects the principle that all parts of the same sentence must be considered for its proper construction, which he invoked so triumphantly in overthrowing the Hamiltonian claim of a substantive power in these words, and holds that these words “common defense and general welfare” have no relation to any part of the sentence, except the first clause of section 8. Is it consistent or logical that a principle adopted in solving the one construction of a sentence should be rejected in the other? And if a general expression, as he holds, may be qualified and explained by subsequent specific grants or qualifications in the subsequent parts of the same sentence, why should seventeen specific and independent grants to Congress be denied any place in aiding in another construction of the same, sentence. In his argument against the Hamiltonian theory, Judge Story has forged a weapon that must, in the minds of all intelligent people, prove fatal to that theory. It is beyond question sound, reasonable, conclusive and irresistible; but that same weapon forged by his own hand, conceived and worked out in his own brain, will, to the same minds, prove fatal to his claim that the words “common defense and general welfare” are only limitations upon the taxing power, for in reaching this conclusion, he has been forced to repudiate the basic principle, that made his former argument irresistible. Byron has well interpreted Judge Story’s position in the lines :

“So the struck eagle stretched upon the plain,

no more through rolling clouds to soar again.

Viewed his own feather on the fatal dart,

That helped to wing the shaft that quivered in his heart.”

III

The argument from section 913, et. seq., to sustain the position that these words constitute only a limitation on the taxing power, is labored and unsatisfactory; it is a repudiation, distinct and complete, of the whole fabric of his former argument, in which he unhorses the Hamiltonians who hold that these words constitute a substantive grant of power. In section 909, 910, 911, he builds up what seems to be an impregnable wall of logic, and in sections 912 and 913 et. seq., he seeks to batter down the wall he has builded. The two arguments must be read carefully together to see their inconsistency. In the second, he refuses to recognize the principles of his first argument and ruthlessly ‘bastardizes his own issue.’ See his language in section 913:

“It is no sufficient answer to say, that the clause ought to be regarded, merely as containing ‘general terms, explained and limited, by the subjoined specifications, and therefore requiring no critical attention, or studied precaution;’ (President Madison’s letter to Mr. Stevenson, November 27, 1830) because it is assuming the very point in controversy, to assert, that the clause is connected with any subsequent specifications.”

Here he asserts that there is no connection between the clause “to pay the debts and provide for the common defense and general welfare” and the subsequent grants of power in the same sentence. Turn to Section 910 and read what he says:

“Shall one part of the same sentence be excluded altogether from a share in the meaning; and shall the more doubtful and indefinite terms be retained in their full extent, and the clear and precise expressions be denied any signification? For what purpose could the enumeration of particular powers be inserted, if these and all others were meant to be included in the preceding general power?”

Here he frankly states that every part of a sentence must be construed with other parts to secure a reasonable meaning and that the words, “common defense and general welfare” are connected with every part of this sentence, with every specific grant of power; while in Section 913 he claims that they are connected only with the first clause.

Again, he says in Section 913:

“It is not said, to ‘provide for the common defense, and general welfare, in manner following, viz.,‘ which would be the natural expression, to indicate such an intention. But it stands entirely disconnected from every subsequent clause, both in sense and punctuation; and is no more a part of them than they are of the power to lay taxes.”

In this he is asserting again that there is no connection between these specific grants of power in this whole sentence, involving the whole of section 8, though he has based his argument against the Hamiltonian claim upon the fact that the words “the common defense and general welfare” must be considered in relation to every part of the sentence for its proper construction. Section 8 of Article 1 constitutes one sentence. The eighteen grants of power arc distinct and separate, and the words in the first clause, “the common defense and general welfare,” he says in his first argument, must be construed with reference to the whole sentence. The clauses are “distinct as the billows,” but the sentence is “one as the sea.” It is seen in this last quotation also that the learned Judge claims that the omission of the words “in the manner following, viz.” following these words in clause 1 is fatal to our pretenses. In Section 910 he uses this language:

“Nothing is more natural or common, than first to use a general phrase, and then to qualify it by a recital of particulars.”

He does not say here that it is usual to follow it by a videlicet, as follows, or in manner following, to-wit.

A simple example will serve to clarify this question. Here is a contract which reads:

“This contract between William Johnston and Warren Grice of the City of Macon, Georgia, witnesseth:

“That said Johnston agrees to build for the said Grice a large, commodious, and convenient residence on a specific lot in said city of the best material in all respects; the house to contain 10 rooms, of which 6 are to be bedrooms, a dining room, parlor, kitchen, and pantry, and 4 bathrooms, 3 upstairs and 1 downstairs; the dining room to be 20 by 30 feet in dimensions, of oak floor; the parlor to be 25 by 35 feet, of maple floor, and on his part said Grice agrees to pay said Johnsion, on the completion of the building, the sum of $25,000.00.”

Under this contract Johnston has agreed to build for Grice “a large, commodious, and convenient house of the best material in all respects” in the first clause of the contract; but this clause has been modified by subsequent enumerations which explain what is meant by “a large, commodious, and convenient house.” Can Johnston meet the demands of this contract by building Grice a house, with a dining room 15 by 20 feet, a parlor 20 by 20 feet, with 8 instead of 6 bedrooms, and with 2 instead of 4 bathrooms, with dining-room floor of North Carolina pine and the parlor floor of oak? Is it not perfectly dear, under the proper construction of the contract, that the unlimited discretion conveyed in the words “a large, commodious, and convenient house, of the best materials in all respects,” is explained and modified by the subsequent words giving the number and size of rooms, character of floors, and so forth? The real meaning of this contract is that Johnston has agreed to build Grice a house with a certain number of rooms; certain number of bathrooms, with the floors of the rooms specified of certain material, the size of each clearly indicated, and that when this is done the house will be regarded by Grice as “a large, commodious, and convenient house.” In other words, the specific enumerations constitute the real contract, and the words in the first clause are merely words of general import. And so “the common defense and general welfare” are explained in their meaning by the enumerated clauses that follow in the same sentence.

IV

In discussing the argument made by his opponents that these words were merely general terms, that were explained by the subsequent specific enumerations of grants of power each involving and being a part of the common defense, or general welfare of the United States, Judge Story says in Section 912:

“But there is a fundamental objection to the interpretation thus attempted to be maintained, which is, that it robs the clause of all efficacy and meaning. No person has a right to assume that any part of the Constitution is useless, or is without a meaning; and a fortiori no person has a right to rob any part of a meaning, natural and appropriate to the language in the connection in which it stands.”

Now, it may be admitted that these words would have a natural and appropriate meaning as a qualification or limitation on the taxing power, if this first clause was a complete sentence, but it is only one clause of a sentence of eighteen clauses, and his argument heretofore, as I have shown, is that these words have a relation to every part of this sentence and must be considered in the construction of each clause of the sentence, and hence the error of his assumption.

But Judge Story also assumes that there must be a limitation on the taxing power in the Constitution in order to reach his conclusion, but why should there be? His assumption of such necessity is to “force the answer,” as the children used to say at school when they lacked a link to make the solution of their problem complete. Suppose the words “to pay the debts and provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States” had been omitted from this clause, (and they were not put in the clause until September 4th) would there have been no limitation on the taxing power? It is recognized by all authorities that the taxing power of a government, without special limitation or specification, extends only to the execution of the functions or powers of that government. Judge Miller, in Loan Association vs. Topeka (20 Wall. 655) has laid down this principle as to our own government, declaring that all taxation must be for public purposes, i e. to carry out the powers granted to the government, and the syllabus of the case (5) says,

“Among these is the limitation of the right of taxation, that it can only be used in aid of a public object, an object which is within the purpose for which governments are established.”

Judge Cooley, (“Cooley on Taxation,” 2nd edition, page 110) says on this subject:

“General Expenses of Government”

“Every government must provide for its general expenses by taxation, and in these are to be included the cost of making provision for those public needs or conveniences, for which, by express law or general usage, it devolves upon the particular government to supply. As regards the Federal government, a general outline of these is to be found in the Federal Constitution. That government is charged with the common defense of the Union, and for that defense, it may raise and support armies, create and maintain a navy; build forts and arsenals; construct military roads, etc. It has a like power over the general subject of post offices, post roads and over other subjects enumerated in the Federal Constitution and subjected to its authority. It may contract debts and must provide for their payment. For all national purposes, it may levy taxes and its power in so doing to select the subjects of taxation and to determine the rate and the methods is as full and complete as can exist in any sovereignty whatsoever, with the exceptions which are provided by the Constitution itself.”

So that if these words had never been put into Article I, section 8, clause 1, the taxing power would have been limited to carrying out the powers granted by the Constitution to the Federal Government and no other. But the framers of the Constitution left this matter in no doubt, for the eighteenth clause of this section 8, after enumerating one by one seventeen grants of power, reads:

“The Congress shall have power to make all laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into execution the foregoing posters, and all other powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States, or in any Department or Officer thereof.”

This coefficient clause therefore constitutes the constitutional limitation on the taxing power of Congress; but any law passed by Congress to carry out an express grant must be necessary and bona fide appropriate to the end. So Congress, desiring to carry out some regulation of commerce that requires an appropriation, may by law appropriate money for it under this coefficient clause, for the end is legitimate and the appropriation is bona fide appropriate to the end. So as to every other grant of power to Congress that may require money.

And so we find that judge Story’s interpretation that these words constitute a natural and appropriate limitation on the power to lay taxes is useless and unnecessary, as the true interpretation is supplied by the Constitution itself in the coefficient clause, which gives to Congress in the disposition of money raised by taxation, the right to dispose of it wherever necessary and wherever bona fide appropriate to carry out a power granted by the Constitution to the Congress. Why, then, should Judge Story supply an interpretation which the Constitution itself clearly supplies? Why provide a limitation upon the taxing power when the Constitution itself has clearly provided it in this eighteenth clause, known as the coefficient clause?

V

But it is clear that these words do not constitute a limitation upon the taxing power of Congress as contended by Judge Story but an expansion of its taxing power, as will be shown. If these words had been omitted, the limitation upon the taxing power supplied to Congress in the coefficient clause, limits Congress in its appropriations to “the foregoing powers,” that is, the enumerated National powers; whereas, under Judge Story’s construction, that slight limitation is brushed aside; and wherever sympathy, or emotion, or the political bias of Congress may conclude that an appropriation will be for the general welfare, whether it be to carry out a National power, a local power, or a power exclusively in the States, Congress may do it; a power as broad as the boundless seas and as infinite as the firmament, embracing the whole field of human desires and human cupidity, with no guide but its own will; with no restraint, but its own discretions; with no Constitution but its own fiat, and no law but its own power.

The proposition of Mr. Hamilton would have given Congress unlimited power to create receptacles and then fill them up with appropriations from the treasury. Judge Story stoutly denies such power as intended to be given in the Constitution, but claims the power in Congress to appropriate money to any persons, associations, or corporations if in their opinion it would conduce to the general welfare of the people. Under this view the courts are without power to obstruct any such measure, as it is to be left to Congress alone to determine, and not the courts. Judge Story denies that the Hamiltonian claim could be sound because it would make of the Government one of unlimited powers, which he says, as we have seen, was never intended by the Convention; but if Congress is without restraint in selecting objects of appropriation, and the tax power is likewise unlimited, is it not apparent that the union of these two unlimited powers in Congress creates a government of unlimited power? The roads may be different that lead to the same end, but it the end, a government of unlimited power, which Judge Story well says, was never intended be the same, his construction must be rejected, as it leads inevitably to the same result, if not to a worse result.

But Judge Story’s construction of these words as a limitation of the taxing power of Congress is subject to a fatal objection for another reason. The general welfare of the United States is made up of the welfare of the people in the several States, in relation to some particular object. Now, while this object may permeate the whole country in the welfare of the people, it may be a subject which, under the Constitution, must be regulated by the States and therefore denied to the Federal Government, for it is well known that Congress can legislate only under the powers granted to it, while all else, under the Tenth Amendment, is left to the several States for their determination. So that, the general welfare may be, and often is, claimed in a subject which is confessedly within the power of the States alone to control. If the special general welfare sought to be obtained is included in the power to regulate commerce, or establish post offices or post roads, or any of the granted plowers, Congress clearly has the power to appropriate, for it under the coefficient clause, but not under the general welfare clause; but if the object should be education, or maternity, or vocational rehabilitation, or any other subject under the exclusive control of the Slates, it must be denied, as Congress has no power to control those subjects.

If, therefore, the object selected by the Congress for legislation under the general welfare is, under the Constitution subject to the control of the States, Congress has no power to legislate or to appropriate money for such object, for if the Constitution gives the power over this subject to the States, of course the act of Congress is void. Take, for instance, the proposed educational bill, the subject of which under the Constitution is reserved to the Slates for their determination; in a case of this character, it may well be that the general welfare of the United States would be promoted by the education of every child in every State in the Union, but since the States alone have the power to control education, Congress, of course, cannot assume that duty. The Tenth Amendment settles this question. Judge Marshall’s statement in Gibbon vs. Ogden cannot be repeated too often. It stands as the irrefutable argument against the doctrine of appropriating money for the general welfare of the United States. In Gibbons vs. Ogden, in discussing the powers of taxation, the power belonging to the States and the Federal Government alike, he uses this language :

“Congress is authorized to lay and collect taxes, to pay debts, etc. This does not interfere with the power of the States to tax for the support of their own governments, nor is the exercise of that power by the States the exercise of any portion that is granted to the United States.

“In imposing taxes for State purposes they are not doing what Congress is empowered to do.

“Congress is not empowered to tax for those purposes which are within the exclusive power of the States.”

And what purposes or objects are within the exclusive power if the States? Everything except those granted to Congress in the Constitution. This simple statement of the great Chief justice, who did more to expound the Constitution than any man who ever sat upon the Supreme bench, is the complete and final answer to the absurd claim of the existence of a general welfare clause, under which, it is claimed, Congress can appropriate money for any cause that they may deem for the general welfare of the people of the United States.

Judge Story’s conclusion that these words “common defense and general welfare” are simply a limitation upon the taxing power of the Government, while denying to them any constructive power, results in this anomalous condition, that the Federal Government, under these words, can construct or create no instrumentality unless the power be granted in the Constitution, but may yet appropriate the money raised by taxation to such organization constructed by the States or other power; that is, that while the Congress could not create a university in every State, it would have the power, if in its opinion it was for the “general welfare” to appropriate money to run them after being established by the States.

But an analysis of these words will show that that this cannot be admitted, for look again at these words critically, “to pay the debts and provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States.” Note the words in this phrase, “of the United States.” Why were they inserted? Suppose this clause read,

“The Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes, etc….to pay the debts … of the United States.”

What is the meaning of the word “United States” in that clause? Would it mean to pay the debts of the people of the United States, or pay the debts of the Government of the United Stales? The words “the people” are omitted, and, in this form, clearly it would mean the debts of the United Stales Government. The words “United States” would, therefore, mean the Government of the United States, under the Constitution. Now, supply the omitted words in the above paragraph, “and provide for the common defense and general welfare”; must not the words “United States” mean the same as to both the payment of debts and common defense and general welfare? They are connected by the conjunctive “and.” So that this careful examination of the sentence shows beyond question that the common defense and general welfare contemplated was not that of the people of the United States but of the Government of the United States, and, therefore, when under this construction, an appropriation of $1oo,000,000 is asked for out of the treasury to be applied to education in the States, there is no authority for it even under this supposed general welfare clause, because it specifically declares that the debts to be paid and the welfare to be secured are not those of the people of the United States, but of the Government of the United States. We find this view powerfully confirmed in an address of Mr. George Ticknor Curtis, a scholarly student of the Constitution, delivered before the Georgetown University Law School in February, 1886 [sic].

VI

If Judge Story’s interpretation of this clause be admitted, namely that these words are merely limitations on the taxing power of Congress, the real difficulty is still left unsolved, for he assumes, once it is granted that they are merely words of limitation on the taxing power, that Congress is clothed with the power of determining what is the common defense and general welfare. But this is mere assumption. If no definition or description of these words is found in the Constitution, and if the Constitution failed to give their meaning, there might be some reason to adopt his suggestion; but if there be a reasonable construction of the Constitution defining these words, why should that reasonable construction be set aside to give to Congress an unlimited control over the whole Government, which Judge Story has so eloquently decried? What is the common defense? What is the general welfare of the United States, Who is to determine this common defense and general welfare? What authority, under the Constitution, has the power to say what objects come within these two terms’ If taxation can be had legitimately to meet the demands of these two extensive terms where shall taxation end? What are its limits? If the objects to which taxation can be applied are unlimited, then the union of the power of taxation with the power of determining the objects to which it may be applied constitute the most tremendous engine of oppression of a free people every [sic] conceived of by the ingenuity of man. Yet, Judge Story assumes that Congress has the power to determine what is the common defense and what is the general welfare of the United States, and that when Congress has determined that a certain object is for the common defense or the general welfare, it may appropriate the tax money which it is authorized to levy, for that purpose. This unites in Congress two great powers, dangerous because unlimited, the one to select the objects of its favor, and the other the power to appropriate money from the treasury for such objects. The unlimited power to tax and the unlimited power to determine their benefactions, are, by Judge Story, united in the Congress, and yet Judge Story (Section 909) affirms that this Government was intended to be a government of limited powers only. The relief from this illogical impasse, into which the learned Judge would drive us, is found in the simple examination of Article I, section 8. clause 1, and the seventeen succeeding clauses, constituting the whole sentence. The manner in which this Article was considered and adopted in the Convention, the care with which each grant was discussed and adopted, constituting the limitations on the powers of Congress, show conclusively that no one power, which could submerge all other powers, was ever intended by the framers oi the Constitution.

A close examination of this first clause and the relation of the words “to provide for the common defense and general welfare of the. United States” to the whole sentence will result in clarifying the situation. Clearness often follows confusion in construing a sentence by changing the location of its paragraphs, not the words, and will often bring out the real meaning of a sentence which seemed cloudy and uncertain. Judge Story says in order properly to understand this clause, the words “in order to” should be inserted before the words “to pay the debts”, (Section 969); and as we are considering merely the phrase “the common defense and general welfare”, we will omit the words “to pay the debts” in the changes suggested below of clause one of this section. By a change of the collocation of the paragraphs, without the change of words or punctuation, clause 1 of section 8 above would read:

“The Congress (in order to) provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States shall have power to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts, and excises; but all duties, imposts, and excises shall be uniform throughout the United States.”

Under this arrangement, the first, second, third, fourth, and so on down through the eighteen clauses would read as follows:

“The Congress…(in order to) provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States shall have power to borrow money on the credit of the United States.”

The third clause:

“The Congress…(in order to) provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States shall have power to regulate commerce with foreign nations, etc.”

The fourth clause:

“The Congress…(in order to) provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States shall have power to establish a uniform rule of naturalization, etc.”

And so on through all of the eighteen clauses. This form of the sentence, which involves no change in the paragraphs or words or punctuation of these clauses as adopted by the Convention on the 4th of September, and which is now in the Constitution of the United States, shows conclusively that the object of the framers of this clause was to provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United Stales by giving Congress the powers granted in the eighteen enumerated powers.

Four men of great eminence have shown that the eighteen specific grants of power in this sentence constituting the whole of section 8 constituted the general welfare which the Federal Convention had determined to be necessary for the Government of the United States, and no more.

Judge Cooley in his “Constitutional Limitations’, page 11, says:

“The general purpose, of the Constitution of the United States is declared by its founders (in the preamble of the Constitution) to be ‘to form a more perfect union, establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and to our posterity’. To accomplish these purposes, the Congress is empowered by the 8th section of article one:–

“(l). To lay and collect taxes, etc

“(S). To borrow money, etc.

“(1). To regulate commerce”, etc.. etc.

enumerating the 17 specific grants of power in this section. (See also the same author, “Cooleys Constitutional Limitations”, pages 11 and 106). Here Judge Coolev first quotes the preamble of the Constitution, which declares that one of the objects for the formation of the Government is to provide for the common defense and general welfare, and adds the significant words that the Constitution has provided a means for accomplishing that by the Federal Government, and that is by laying taxes, borrowing money, regulating commerce, amd adopting the 17 specific grants as that “common defense” and that “general welfare” which the Convention concluded was sufficient for the purpose.

James Wilson, a member of the Federal Convention, afterwards on the Supreme Court of the United States, has indorsed this view most strongly. (Wilson’s Works, Andrews, Vol 11, pp. 56-59):

“Once more, at this time: The National Government was intended to ‘promote the general welfare.’ For this reason Congress has power to regulate commerce with the Indians and with foreign nations and to promote the progress of science and of useful arts by securing for a time to authors and iventors an exclusive right to their compositions and discoveries.

“An exclusive property in places fit for forts, magazines, arsenals, dock yards, and other needful buildings, and an exclusive legislation over these places, and also for a convenient distance, over such district as may become the seats of the National Government—such exclusive properly and such exclusive legislation will be of great public utility, perhaps of evident public necessity. They are therefore vested in Congress by the Constitution of the United States.

“For the exercise of the foreign powers and for the accomplishment of the foregoing purpose, a revenue is unquestionably indispensable. That Congress may be enabled to exercise and accomplish them, it has the power to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts, and excises.

“The powers of Congress are, indeed, enumerated: but it was intended that those powers thus enumerated should be effectual not nugatory. In conformity to this consistent mode of thinking and acting Congress has power to make all laws which shall he necessary and proper for carrying into execution every power vested by the Constitution in the Government of the United States or in any of its officers or departments.”

The learned judge gives no hint in this statement that the “general welfare” was anything more than a description of those powers which were subsequently enumerated in the Constitution. There is not an intimation in his statement that Congress has any other power than those which are enumerated, and that the words “to provide for the general welfare” are merely a general description of that welfare, which is to be accomplished by carrying out certain enumerated powers.

Hon. Benjamin J. Sage of New Orleans some years ago published a remarkable book entitled “The Republic of Republics”. It is a wonderful repository of most interesting criticism and commentaries on the Constitution, In discussing this question he affirms what has already been stated, that often times the meaning of a sentence may be clarified by changing the collocation of the clause without the change of the words or punctuation, and adopting this method he arrives at the same result which Judge Coolev and Judge Wilson have arrived at, and he says that this section, with those changes, would read as follows:

“Sect. 8 The Congress, (in order to) pay the debts and provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States, shall have power—

“To lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts and excises;

“To borrow money;

“To regulate commerce”; etc.

and so on, continuing through the seventeen grants of power.

Mr Otis of Massachusetts in the Fifth Congress (Sec Annals of Congress. 1797-99, Vol. 8, page 1986) indorses the same view in the following language:

“Mr. O. agreed that the construction was just which the gentleman put upon the first article of the eighth section of the Constitution, and that to provide for the common defense and general welfare was the end of the powers recited in the first part of that section, and that the powers were merely the means. But this is equally the end of all the other powers given to Congress by all the articles of this section, so that these words might, with propriety, be understood as if they were added to every clause in it, and thus, from the whole section, it appears clear that Congress has a right to male war for the common defense and general welfare, and of course to do everything which is necessary to prepare foe such a state “

In Conclusion

The interested investigator into the meaning of this phrase, injected between the first specific grant of power to Congress and a limitation upon that grant, (which of itself is conclusive against any grant of a substantive power, as claimed by the Hamiltonians) cannot fail to inquire why these words were incorporated into this first clause on the 4th of September 1787 only eleven days before the Constitution was adopted, after the Convention on the 6th of August had adopted the Pinckney plan on this subject without these words. And especially is this inquiry most pertinent in reference to the words “to pay the debts”, for without these words we have shown that the power of Congress to pay the future debts of the Government of the United States was already secured in the coefficient clause, and the old debts of the Government were secured in a subsequent clause of the Constitution. The answer is to be found in a fact which was thoroughly demonstrated in the discussions in the Convention, showing an intense and determined feeling on the part of its members that there should be no doubt as to the integrity of the new government, in its obligations to its creditors. Repudiation was rampant throughout the country; States were passing laws to repudiate their debts to foreign creditors, and this feeling and spirit pervaded the whole country; and a number of propositions had been offered and passed during the proceedings of the Convention emphasizing the duty of the payment of the debts of the United States; and the founders of this great Republic were determined that the integrity of the new Government should never be questioned and that this should be made clear in the Organic Act. In response to this feeling these words “to pay the debts” were determined upon, and they were inserted, naturally and suitably, after the power “to lay and collect taxes.” But when that was done, see the effect of it.; The clause then would read:

“The Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts, and excises, to pay the debts, but all duties, imposts, and excises shall he uniform throughout the United Slates.”

Such a provision might have been construed as giving Congress the power to lay and collect taxes to pay the debts, and only for that purpose; what was to become of the other seventeen grants of power that needed money to carry them out ? What about commerce, post offices, post roads, if the expression “to pay the debts” had been left alone in the clause? Expressio unius exclusio est alterius. Such a form, to say the least, might have endangered the right of Congress to appropriate to the other specific grants of power. So some words had to be added to those “to pay the debts” that would make clear the power of Congress to appropriate for all federal purposes, as set forth in the subsequent enumerated grants. What should those words be? Three times in two days, on the 22nd and 2srd of August, the Convention indorsed a resolution of this nature: That the Congress should “fulfill the engagements and discharge the debts of the United States”. What engagements had the United States? They are chiefly specified in the eighteen specific grants in the Pinckney plan finally adopted August 16th. Do not the words “fulfill the engagements” interpret the meaning of “common defense and general welfare”? Are not those the only engagements of the Government Of the United States? Undoubtedly, having determined for the honor of their country that there should be an express provision to pay the debts some other words would have to be supplied to save to the Congress the right to carry out the grants of power to Congress thereinafter enumerated, and to show that its power to appropriate money was not confined alone to the payment of the debts. What should these additional words be? They selected these words: “To provide for the common defense and general welfare” as they embraced all the subsequent grants of power which the Convention had already determined should constitute that amount of common defense and of general welfare which the Federal Government ought to control; and being merely words of general import and without power in the Articles of Confederation from which they came, brought with them to the Constitution of the United States the same innocuous character.

Now follow the steps in their adoption.

On in the 31st of August, on motion of Mr. Sherman, a committee of eleven was appointed, to whom was referred “such parts of the Constitution as have been postponed and such parts of reports as have been acted on”. This committee consisted of Gilman of New Hampshire, Rufus King of Massachusetts, Roger Sherman of Connecticut, Brearly of New Jersey, Gouverneur Morris of Pennsylvania, Dickinson of Delaware, Carroll of Maryland, Madison of Virginia, Williamson of North Carolina, Pierce Butler of South Carolina, and Abraham Baldwin of Georgia. All except Morris and Brearly had served in the Continental Congress, and were familiar, therefore, with the Articles of Confederation, and the lack of power of the words in these Articles.

On the 4th of September they reported that clause 1 of section 1, Article VII of the Pinckney plan should read :

“The legislature shall have power to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts and excises, to pay the debts and provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States.”

And the claim is made by the followers of Mr. Hamilton that these words constitute a substantive grant of power to Congress to pass all and any laws effecting the general welfare of the people of the United States; and while Judge Story, in a luminous argument shows such a claim to be preposterous, he claims that, under these words, Congress may make appropriations for any object which in their judgment they may believe to be for the common defense or general welfare of the people of the United States, i. e., that Congress can appropriate money to an institution that it is denied the power to create. The question, therefore, is brought sharply to this issue: Did the men constituting this committee intend, by the insertion of these words, to destroy the Pinckney plan containing only specific grants of power to Congress, which had been passed unanimously by the Convention without a single negative vote on the 6th of August previously? An examination of this committee will show that the majority of them could never have agreed to any such proposition. The known sentiments of at least seven of them, and probably nine, show conclusively that their insertion of these words was never considered by them as authorizing the construction put upon them by the Hamiltonians, or by the learned Judge Story. Among this number, Mr. Madison stands out preeminently as having shown and demonstrated beyond question that these words did not have, and could not have, such meaning. The evidence of their positions may be gathered from several sources.

Mr. Abraham Baldwin, a member of this committee, on June 17, 1798, as a Member of Congress, uses this language.

“That part of the first article of the eighth section, which declares, ‘Congress shall have power to provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States’ had never been considered as a source of legislative power as it is only a member introduced to limit the other parts of the sentence, and not of itself a substantive power, as will be seen by recurring to the words of the first sentence of the eighth section.”

On the 16th of July, in the Convention, Mr. Pierce Butler, also a member of this committee, and Mr. Gorham of Massachusetts and Mr. Rutlcdge of South Carolina were participants in a debate in the Convention which showed Mr. Butler was favorable to specific grants of power to Congress, and was objecting to general and indefinite grants that were suggested. But there was one gentleman on the committee, Mr. Gouverneur Morris of Pennsylvania, who knew that these words as reported by the committee were the death knell to the proposition of Mr. Hamilton, as may be seen from the following incident.

Albert Gallatin of Pennsylvania had been a member of the Federal Convention; he was one of the most distinguished men uf his day. On the 16th of June, 1798 as a Member of Congress, he made a speech on this clause in which be said:

“He (Gallatin) was well informed that these words had originally been inserted in the Constitution as a limitation to the power of laying taxes After the limitation had been agreed to and the Constitution was completed, a member of the Convention, (he was one ot the members who represented the Slate of Pennsylvania) being one of a committee of revisal and arrangement, attempted to throw these words into a distinct paragraph, so as to create not a limitation, but a distinct power. The trick, however, was discovered by a member from Connecticut, now deceased, and the words restored as they now stand. So that Mr. Gallatin said, whether he referred to the Constitution itself, to the most able defenders of it, or to the Stale Conventions, the only rational construction which could be given to the clause was, that it was a limitation, and not an extension of powers.” (U.S. Annals of Congress, Fifth Congress, 1797-99, Vol. 8, page 1796.)

For confirmation of the above see “The Framing of the Constitution”, Max Farrand, page 182.

It is of interest to note that Abraham Baldwin, a member of this committee, was a member of tlie Federal Convention and a Member of the same Congress (the Fifth) that Gallatin was, and engaged with him in this debate, and he doubtlessly heard Gallatin’s statement, and there was no denial of it from him.

Who was the member from Pennsylvania in the Convention who attempted this “trick”? It is easy to ascertain who he was. In being designated as one of a committee of revisal and arrangement in the Convention we find that the member from Pennsylvania on that committee was Gouverneur Morris, who, it is seen, is also a member of this committee of eleven that brought in this report. And who was the member from Connecticut that discovered the “trick”? By the process of elimination this is easily discovered because Mr. Gallatin said “he is now dead”. The words were spoken in 1798. Johnson, Ellsworth and Roger Sherman were the members of the Convention from Connecticut. Johnson and Ellsworth died after 1800, and Roger Sherman died in 1793; and Roger Sherman, who detected this “trick”, was a member of this committee of eleven that brought in this report, and, having prevented Morris from making the change by throwing these words into a distinct paragraph, it showed first that Sherman was opposed to the unlimited power attempted to be given to these words by Morris’ “trick”, and (second), that Morris was trying to make the change to carry out Hamilton’s idea, because the clause as adopted September 4th was fatal to Hamilton’s desire for unlimited powers.

This “trick” described by Mr. Gallatin as attempted by Gouverneur Morris arose out of the fact that on the 8th of September the Convention appointed a committee “of five to revise the style and arrange the articles agreed to by the House”. The committee was composed of Samuel Johnson, Hamilton, Gouverneur Morris, Madison and King, and on the 12th of September that committee made its report and Article 1, section 8, appears as follows:

“Sect. 8. The Congress may, by joint ballot, appoint a treasurer. They shall have power to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts, and excises;

“To pay the debts and provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States;

“To borrow money on the credit of the United States;

“To regulate commerce with foreign nations, among the several states, and with the Indian tribes;” etc., etc. (Journal of Federal Convention—Boston—1819.)

Had the Constitution been ratified in that form, there would be considerable ground for asserting that it contained the Hamiltonian idea of unlimited power.

Another evidence of the views of this committee is to be gathered by the statement made by Luther Martin, one of the greatest figures in the Convention, who, on his return home, addressed the Maryland Legislature, giving an account of the Convention. In it he said there were three parties in the Convention; first, the Hamiltonians, who desired to annihilate the States and establish a government of a monarchical nature ; secondly, those who were opposed to the abolition of the States and the adoption of a monarchical government, but who wished tor greater powers for the great States in the Union; and third, “was what I consider truly federal and republican; this party was nearly equal in number with the other two and was composed of the delegations from Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Delaware, and in part from Maryland: also of some individuals! from other representations”.

On this committee of eleven were Mr. Sherman from Connecticut, Mr. Brearly from New Jersey, Mr. Dickinson from Delaware, and Mr. Carroll from Maryland.

Prof. Beard, in his book “Economic Origins of Jeffersonian Democracy”, page 35, says of Abraham Baldwin:

“Baldwin was in the opposition from the beginning and remained a consistent Republican until his death.”

Mr. Jefferson said of John Dickinson of Delaware that he was “an orthodox advocate of the true principles of our new government. (Jefferson’s Works (Washington ed.) Vol. V, page 249).

In “The Framing of the Constitution” by Max Farrand, page 81, he mentions a number of the members of the Convention who advocated a strong national government and those who were opposed to such, among the latter, he names Sherman, Brearly, Dickinson and Butler.

The position of Hugh Williamson of North Carolina, a member of the committee of eleven might well be determined alone by the position of North Carolina in refusing to ratify the Constitution for two years because of the need of amendments. As a member of the second North Carolina convention called to ratify the Constitution his position is more clearly seen by a motion made by him to ratify the Constitution as concluded at Philadelphia September 17, 1787. As the Constitution contained, when passed, the exact form of this section and clause recommended by the committee of eleven on the 4th of September, the conclusion is final that he favored that form. (See “North Carolina States Records,” Vol. 22, page 41, Raleigh, 1907).

Thus we find in our conclusion that there is no general welfare clause in the Constitution; that the power of Congress to legislate for every object which in their opinion might be for the benefit of the people, pressed by Mr. Hamilton in the Convention, was six times, directly or indirectly, rejected by that body; and, in spite of that, his followers have sought to construe these words as meaning what the authors of the Constitution had six times successively rejected; while Judge Story’s construction lands us in the same morass, a government of unlimited power, though he reaches it by a different road.

These facts show that a large majority of the Committee of Eleven that reported these words to be incorporated into the first clause of §8 Art. I were strongly opposed to the views of Mr. Hamilton and those of Judge Story that lead to the same end, tho’ by different routes, a government of unlimited powers!!

In support of our views, we present a long catalog of distinguished statesmen, judges and authors, who sustain our position:

Primus inter pares. Chief Justice Marshall in McCulloch v. Maryland, 4th Wheat. 316.

Gibbons v. Ogden, 9th Wheat. 1.

Virginia Constitutional Convention, 1829-30, on the militia.

Judge Brewer in Kansas v. Colorado, 206 U. S. 89, and Fairbanks v. United States, 181 U. S.

Judge Miller in Loan Association v. Topeka, 20 Wallace 655.

fudge Miller on the Constitution, page 229, note 2.

Mr. Madison, Resolutions of 1798.

Mr. Madison’s Message May 4, 1822.

Federalist No. 41.

Veto Message March 3, 1817.

Letter of Madison to Andrew Stevenson.

Supplement to letter to Andrew Stevenson. (Writings of James Madison by Gaillard Hunt, Vol. IX, page 424).

Cooley on Taxation. 2nd edition, page 110.

Cooley, Constitutional Limitations, pages 11 and 106.

Willoughby on the Constitution, Vol. 1, page 40.

James Wilson (Wilson’s Works–Andrews–Vol. 2, pages 56-59).

John C. Calhoun, February 20, 1837. U. S. Senate. (Works of Calhoun, Vol. III, page 36).

Mr. Jefferson on power of Congress to establish Bank of the United States, February 15, 1791.

Letter to Judge Spencer Roane, October 12, 1815, (Works of Jefferson by Paul Leicester Ford, 1905, Vol. XI, page 489).

Von Holst, a strong Federalist, Constitutional Law of the United States, page 118.

Hare, American Constitutional Law, Vol. I, page 242-243.

William A. Duer, Constitutional Jurisprudence, 2nd edition, page 211.

Grover Cleveland, veto message to the House of Representatives making appropriations for drought-stricken counties in the Southwest

B.J. Sage in “Republic of Republics”.

Calvin Coolidge, addresses of, Budget meeting January 21, 1924, and Annual Message December 8, 1925.

Tucker on the Constitution, Vol. I, pages 477-478-480.

And who upholds the opposite view? Judge Story and Pomeroy. Where lies the weight of authority?