The mission of the Abbeville Institute, to redeem what is worthwhile in the Southern tradition, is an embattled one. The dominant powers in American discourse today have succeeded in confining the South to a dark little corner of story labeled “Slavery and Treason.” This is already governing the public sphere of the Civil War Sesquicentennial. Such an approach not only libels the South, it is a fatal distortion of American history in general, and, I dare say, even of African-American history.

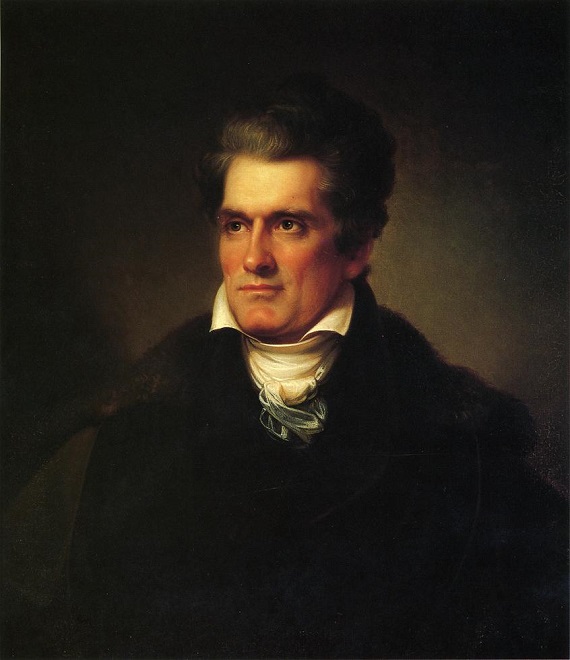

The old Radical Republican propaganda that portrays John C. Calhoun as a scheming fanatic who brought on civil war by his determination to spread slavery has re-emerged. A little over a half century ago, the historiographical picture was quite different. Margaret Coit’s admiring biography won a Pulitzer Prize. A leading expert on the subject wrote that Calhoun understood the mysteries of banking and money better than anyone else at the time. Numerous scholars, mostly of a liberal and progressive disposition, praised Calhoun’s concurrent majority as a brilliant and useful concept. A United States Senate Committee chaired by John F. Kennedy named Calhoun one of the five greatest Senators of all time.

One is tempted to conclude that historical knowledge is not cumulative and to agree with Orwell that who controls the present controls the past, and who controls the past controls the future. Certainly the present discourse reflects not historical judgment but a political/ideological agenda.

In the Jacksonian era, so-called, I have learned that one must not only look for political bias, one must look for comic book versions of history. One noted historian of the period, who has appeared often on television as a savant, once asked me to verify a quotation about Henry Clay often attributed to Calhoun. Calhoun is supposed to have said something like “Henry Clay is a scoundrel, but, by God, I love him.” You don’t have to spend much time with Calhoun to understood that both the language and the opinion are phony. With much work I found the origin of the quotation. It was in a dubious book published in the 1890s by a social butterfly (male) who claimed to know everybody of importance. I provided the historian in question with three authentic remarks by Calhoun about Clay, all more interesting than the spurious one. When the book was published I found the same phony material used. I assume because it fits in with his imaginary version of the times that the author wished to portray.

This same writer, in another very well-received book, vividly describes John C. Calhoun grinding his teeth in chagrin because he has been out-witted by Martin Van Buren. How could he possibly know this? What possible benefit to historical understanding is conveyed? Martin Van Buren may have considered politics as a game of wits between different personalities, but Calhoun did not. Historians relentlessly purvey the charge, originating in demagoguery of the times, that Calhoun’s actions are explained by his thwarted ambition to be President. Does such ambition describe a man who broke with President Jackson over a matter of honour, resigned as Vice-President to defend his State, opposed Jackson without joining the opposition party that wanted to claim him, and raised a lonely voice against the Mexican War which threatened his popularity in the South and even in South Carolina? Calhoun understood the American political system better than most, and he knew perfectly well in the last 20 years of his life that he could never be President, and did not much care. If supporters wanted to keep his name out there, that was good, because it enhanced his weight in matters that he did care about.

Calhoun was a major figure very near the pinnacle of American statecraft for forty years. His influence, though never dominant, even in the South, was Union-wide. It was largely moral and intellectual and extended to many more subjects than the sectional conflict. Which is why ambitious politicians of all parties hated him and attempted to reduce his standing by cheap ridicule which some historians continue to retail. Several writers have put forth the proposition that a statesman differs from a politician in that a statesman perceives the long-range consequences of actions, lays out for a society its real alternatives, and, though he usually goes unheard, warns of future dangers. By this rule, Calhoun was indeed a statesman. All politicians and many historians imagine than nothing exists higher than a politician.

In an article in a collection in honour of Eugene Genovese I briefly described Calhoun’s knowledge and statesmanship in regard to economic issues. A perceptive reviewer was kind enough to say that the article “plowed new ground by the acre.” So far, nobody has appeared to plant the ground, and perhaps they never will.

This is my opportunity to do the same for Calhoun on diplomacy and war, where his wisdom, I think, will prove him to have been prophetic. He played a significant role in American diplomacy and war through his entire forty-year career, although a standard diplomatic history of the United States devotes only a half page to him in passing. His acts and words in regard to war are significant, and, since Calhoun is in many ways a definitive Southerner, will be seen to support our enterprise here significantly.

Let us begin with the “War Hawk” of 1811-1816. Calhoun’s first recorded political speech was at a public meeting in Abbeville in 1807 at which he presented and passed resolutions demanding a forceful response to the Chesapeake and Leopard affair. This was not what we are familiar with now—not a peevish demand that the government do something. It was an expression of the willingness of South Carolina to fight for American honour. He arrived at the House of Representatives in 1811, and after his first speech, at the age of 29, the leading Jeffersonian editor of the country called him “one of those master spirits who leave their stamp upon the age in which they live.” Calhoun spoke eloquently for firm and effective response to British hostility and insults. He drafted the resolution embodying the declaration of war when it came. His labour in the House to bring support to the army and morale to the country during the discouraging times that followed led an editor once more to praise him as “the young Hercules who carried the war on his shoulders.”

Calhoun’s rhetoric as War Hawk is informative. He never appealed to desire for new territory or seldom even for commercial redress, though that was worthy of attention. He spoke often, and almost always he spoke of the war in terms of honour. The young country could not submit to a bully. To do so would be to forfeit respect and invite further affront. Americans must have the spirit and the means to repel dangers so they could go about their real business. Characteristic Southern attitude?

The war was far from a great success, beginning with the Connecticut Yankee, General William Hull, surrendering the Michigan Territory to the British without even firing a shot. Calhoun had his work cut out for him. Fortunately, the war ended on a high note with Jackson’s victory at New Orleans, which was achieved by volunteers from nearby Southern States with no thanks due to the government in Washington.

The mess of the war was critical for Calhoun’s later thinking. One recent biographer, of the comic book school, suggests that Calhoun was so badly shaken and scared by the failures in the war that his opposition to war thereafter was a matter of fear. This biographer also states that he ignores Calhoun’s political thought, which he cannot understand and does not think is significant. This biography is so bad that it of course won a prize.

Calhoun’s response was positive and constructive. In 1817 he accepted President Monroe’s invitation to become Secretary of War. Everyone advised against it. Friends said he would lose his place in national attention, make enemies, and take on an impossible job that would surely end in discredit. Others said Calhoun was too philosophical to be an administrator. Calhoun applied his genius to the problems of the defense of a far flung and growing Union. He went to work to make things better. This is another way you can tell a statesman from a politician. A politician does not work. He spends his time posing for attention and on backstairs maneuvers for advantage.

While other ambitious men were posturing for position, Calhoun devoted his years from age 35 to 42 in a grueling but necessary job that would benefit every part of the Union. It is reasonable to say that Calhoun in his seven years in the War Department did more to create the peacetime U.S. Army than any other single individual.

The largest department of the government was literally in a shambles of accounts and accountability. Calhoun instituted a bureau system that is said to have been copied in Europe. The non-combat branches of the army—engineers, commissary, quartermaster, ordnance, medical, and Indian Affairs—became efficient. Incidentally, Calhoun acted upon the idea that most troubles with the Indians resulted from the corrupt and incompetent officials sent by the government to deal with them. Later, in the Senate, he vigourously opposed Jackson’s Indian removals.

Most importantly, Calhoun provided a Jeffersonian solution to the problems of defense—the expansible army. Americans were hardy and patriotic men who could quickly become good soldiers in an emergency. A large, expensive, and possibly dangerous standing army was not required. What was needed was a core of logistical organisation and professional officers who could organise, supply, train, and lead volunteers when needed. An important key to this was West Point, the prestige of which dates from Calhoun’s tenure. The institution was reformed with the best faculty and curriculum available. For a long time West Point was one of the best colleges in the U.S. and certainly the best technical college.

One of his arguments for West Point he had already presented while still in the House, in order to refute the common charge that such an institution would create an aristocratic, unrepublican officer class. The military academy, rather, fit a Jeffersonian educational ideal—to rescue talent from the lower orders. The institution would attract young men who were able and ambitious but without family money. Not all the graduates would make a career in the small peacetime army. After a few years service they would enter civil life where their training would be of great value to a developing country, and from whence they could return to the colours when called.

While still in the House, Calhoun had drawn up a plan of “internal improvements.” This was a masterfully designed system of roads and waterways needed to get men and supplies quickly to threatened points, based entirely on the Constitutional right and duty to provide for the common defense. President Madison found it a good plan but said that a Constitutional amendment was needed to allow it. When Calhoun later opposed “internal improvements” legislation, petty politicians said he had reversed himself. There was no inconsistency because “internal improvements” legislation had devolved into log-rolling and patronage without any system or any relation to rightful federal powers.

Note that all of his plans contemplated a defensive policy only. He did not foresee that the Union would ever have any need for aggression.

Calhoun survived despite rocky conflicts with Congress and false accusations of fiscal misdeeds cooked up by his cabinet associate and presidential rival William H. Crawford. He emerged from the War Department to be easily elected Vice President in 1824 in an election which split the presidential results four ways—the youngest man ever put so near the White House. Despite all, he never overcame the suspicion of the Old Republicans that he was too much of a nationalist. They had already given up on the Union entirely while Calhoun was trying to promote fairness and harmony among its disparate parts. Not until he began to pay close attention to the tariff did he realise that fairness was not reciprocated by dominant Northern interests.

From assuming office as Vice-President in 1825 until his appointment as Secretary of State in 1844, Calhoun was most concerned with internal issues, but established a recognised position on diplomacy and war that was praised by some and deplored by others. In 1836, Jackson sent Congress a message bristling with sabre-rattling threats against France in regard to some long-standing unpaid claims. Calhoun’s comments in the Senate showed that he knew a good deal more about the issue, and about French politics, than the President or Secretary of State, and described several missed opportunities for settlement. To threaten a major power was the surest possible way to guarantee non-compliance, he said. And one day of war would cost more than the entire sum at issue. The President was going about things all wrong.

Was this inconsistent with the War Hawk of earlier years, and merely expressive of venom against Jackson, as the prize-winning biographer would have it? I don’t think so. In 1811 Great Britain was a genuine threat on our coast and our northern border. France in 1836 was not such a case. In fact, in 1811 Calhoun had told the House

A bullying menacing system has everything to condemn and nothing to recommend it—in expense it is almost as considerable as war—it excites contempt abroad, and destroys confidence here. Menaces are serious things, and, if we expect any good from them, they ought to be resorted to with as much caution and seriousness as war itself; and should, if not successful, be invariably followed by it.

Good Southern style, I think. If you have been injured, don’t bluster about retaliation. Issue your challenge soberly and courteously, be open to an apology, and be ready to back up your words. Col. David Crockett, the frontier hero, supposedly had a rule: “Be sure you’re right, then go ahead!” The “be sure you are right” part is important, the difference between a just man and a bully. You will never, ever, hear this anywhere else, but Col. Crockett was an admirer of Calhoun and not of Jackson.

In similar fashion, Calhoun supported ratification of the Webster-Ashburton Treaty in 1842. It settled most of the Canadian boundary and left in place the standing agreement for joint U.S.-British occupancy of the huge Oregon Territory that had been adopted in 1818. There were many in Congress and the newspapers who were making militant demands for immediate settlement of the Oregon question on American terms. These demands would lead two years later to the Democratic campaign slogan “54 40′ or fight!”—a declaration of intent that all of the territory, including what is now British Columbia, up to the Russian border in Alaska, shall be American and not British.

In speeches on this question Calhoun described his vision of the American future. The British were not known to bow to threats. The world was growing more enlightened and comfortable. A war between two great powers would be retrograde for civilisation. He pointed out that a quiet delay was all to the American advantage. Our people were ever enterprising. Give them a little time and they would fill up all the North American territory we could reasonably want and make it de facto American. Was this not preferable to war with the greatest power in the world over a yet sparsely settled territory? Further, he said:

I am finally opposed to war, because peace—peace is pre-eminently our policy. There may be nations, restricted to small territories, hemmed in on all sides, so situated that war may be necessary to their greatness. Such is not our case. Providence has given us an inheritance stretching across the entire continent, from East to West, from ocean to ocean, and from North to South, covering by far the greater and better part of its temperate zone. It comprises a region not only of vast extent, but abundant in all resources; excellent in climate; fertile and exuberant in soil, capable of sustaining, in the plentiful enjoyment of all the necessaries of life, a population of ten times our present number. Our great mission, as a people, is to occupy this vast domain; to replenish it with an intelligent, virtuous, and industrious population. . . . War would but impede the fulfilment of this high mission, by absorbing the means and diverting the energies which would be devoted to the purpose. On the contrary, secure peace, and time, under the guidance of a sagacious and cautious policy, “a wise and masterly inactivity,” will speedily accomplish the whole.

Keep the peace and allow American enterprise to flourish by keeping the federal government confined to “the few great objects for which it was instituted,” and “a scene of prosperity and happiness would follow heretofore unequalled on the globe.” Calhoun’s appeal for “a wise and masterly inactivity” came in for a good deal of ridicule from politicians and press. It is perhaps a natural human tendency to feel that aggressiveness is necessary for advancement. And military success exercises a strong appeal.

I can well imagine those numerous writers who blame the South for every bad thing in American history jumping to the conclusion that Calhoun by these remarks has declared in favour of American exceptionalism, and is therefore guilty of instigating our foreign expeditions to spread democracy. No. He makes an upbeat description of the American potential, but it is the potential for Americans, not for the world, and is spoken in the interest of peace. Compare these words written by the alleged conservative realist John Adams in his diary as early as 1765: “I always consider the settlement of American with reverence and wonder, as the opening of a grand scheme and design in Providence for the illumination of the ignorant, and the emancipation of the slavish part of mankind all over the earth.”

We have in the contrast an illumination of the Southern tradition and the real source of messianic American exceptionalism—New England.

Calhoun left the Senate in 1843 with the intent of staying at home and working on his farming and his treatise on government. In Washington, on 28 February, 1844, Secretary of State Upshur was killed in an accidental explosion during an excursion on a warship. A week later, without Calhoun’s knowledge, President Tyler sent his name to the Senate to be Secretary of State. The nomination was confirmed in a few hours without a single dissent, even from the antislavery Senators of Vermont. Most of the nominations made by Tyler, who was supported by neither party, were routinely rejected. This must tell us something about Calhoun’s standing as a statesman and his reputation as a peacemaker, for the country faced the most serious questions in foreign affairs since the War of 1812—Texas and Oregon.

Secretary of State Calhoun pursued a peaceful settlement of the Oregon question that would make a division of the territory along the present border. Later, in the Senate, Calhoun defended this approach, pointing out the lunacy of brinksmanship with the strongest power on earth, Britannia ruling the waves, over a territory where the U.S. could neither raise nor support an army. When Polk took over, after two years of blustering he was forced to face reality, give up “54 40′ or fight!,” and settle on a treaty along the lines Calhoun had laid out.

Some Northerners complained that while Calhoun was eager to bring the Southern territory of Texas into the Union, he was willing to give away Northern territory. But the questions were not the same. Texas had already shown the ability to defend itself, and Mexico, unlike Great Britain, could inflict little harm on the United States. The desire to have Texas in the Union had been thwarted for ten years because of fear of war and because an increasing number of people had been led to believe that when Northerners moved west it was a noble mission to civilise a continent and when Southerners moved west it was an evil conspiracy to spread slavery.

In 1843-44 Texas had agents in Europe talking with Britain and France about the possibility of an defensive alliance. We now know that this was less serious than it seemed at the time. Influential British forces were already moving to extend their worldwide emancipation campaign to Texas. British influence in Texas would give them a much-desired alternative cotton supply and make the Gulf of Mexico into a British lake, threatening American security and Southern society. Following a policy that Tyler had already initiated, Calhoun negotiated a treaty with the Texas Republic by which it would be annexed to the United States. The treaty failed the necessary two-thirds majority in the Senate. Historians have almost unanimously said the defeat came because Calhoun had described the treaty as a necessary measure against foreign abolitionism. This was probably a tactical mistake, but Tyler and Calhoun accomplished part of what they had intended, which was to illuminate British machinations. The conventional interpretation seems to miss the point. Rejection of the treaty was a party vote. The Whigs had a majority and all but one of them voted nay.

This business was naturally pertinent to the 1844 presidential campaign. The prospective Whig candidate Clay and the Democratic front-runner Van Buren happened to cross paths at Raleigh on the campaign trail. They colluded to deal with the explosive issue of Texas by not discussing it at all. This was the kind of political gamesmanship that Calhoun despised and believed was undermining American republicanism. He always advocated putting the issues plainly before the people. This was one of the reasons he confronted abolitionism frankly when most politicians of both parties accused him of agitation because they wanted to pretend a serious issue did not exist.

By bringing Texas prominently into public attention, Tyler and Calhoun eliminated Van Buren from the running so that the Democratic nomination went to the dark-horse James K. Polk, expansionist. And when Polk won his slim victory Congress admitted Texas to the Union by a majority of both houses, avoiding the treaty process.

It was widely expected that Polk would continue Calhoun as Secretary of State. He was, after all, in the midst of dealing with two important questions. Calhoun had the measure of Polk and knew better. If such a Cabinet were to meet, wherever Calhoun sat would be the head of the table, something Polk was not about to accept. He offered Calhoun the post of Minister to Great Britain, which he knew would be turned down.

Texas now was part of the Union. Mexico did not acknowledge this, and further insisted that the southern border of Texas was not at the Rio Grande but at the Nueces a hundred miles further north. The area in dispute was semi-arid and occupied mainly by wild longhorns. Polk sent the army to the Rio Grande. Inevitably, American and Mexican patrols ran into each other and fought.

When the news finally reached Washington, Polk’s message to Congress said that American blood has been shed on American soil and that a state of war existed. Two days of Congressional wrangling and reluctance followed until both houses adopted, instead of a declaration of war, a resolution recognising the existence of war.

I have said that Calhoun was a prophet. Judge for yourselves. I think you will find that what he has to say about the war with Mexico is just as significant today as it was a century and a half ago.

Calhoun was on his feet at once to criticise. The U.S. and Mexico were at war but there had been no declaration, though this was required by the constitutions of both governments. War should be a considered and deliberate commitment, backed by the people. There were no stated war aims, which made hostilities limitless. Further, what had happened, a border incident, did not necessarily call for all out war, and might be handled in ways short of that.

Worst of all, the President had in effect instigated armed conflict by his action. If this were allowed, then a precedent was set by which any future executive could provoke an incident and commit the country to war by his own decision. Sound familiar? Fort Sumter? “Remember the Maine?” Pearl Harbour? Gulf of Tonkin? “Weapons of mass destruction?” A basic distinction between American republicanism and the monarchical practices of the Old World had been obliterated. The war resolution passed with only a handful of dissenting votes in either house. Calhoun sat silent when his name was called and declined to participate in the fraud and folly. His contempt was further justified when over 60 Whig members of Congress, who had voted for the war resolution because they were afraid of being labeled unpatriotic, immediately voted nay to appropriations to carry out the war.

The Constitution had been thrust aside. Calhoun said to friends “that a deed had been done from which the country would not be able to recover for a long time, if ever. . . it has dropped a curtain between the present and the future” and “it has closed the first volume of our political history under the constitution, and opened the second . . . . “no mortal could tell what would be written in it.” To his closest confidante, his daughter Anna, Calhoun wrote: “Our people have undergone a great change. Their inclination is for conquest & empire, regardless of their institutions and liberty; or, rather, they think they hold their liberty by a divine tenure, which no imprudence, or folly on their part, can defeat.”

As the war successfully proceeded, Calhoun opposed the Polk administration’s campaign to invade deep into Mexico, capture the capital, and force a government that would negotiate away territory. He spoke again and again for limited and justifiable war aims. The Rio Grande was secured. New Mexico and California, which had never been more than marginal parts of Mexico, were ours. Be content with this, he argued, when many voices were being raised for decisive defeat of Mexico and occupation of more of its territory. Calhoun went unheeded. Military success was gratifying and Polk invaded all the way to Mexico City and seized it, involving Americans for the first time in occupation of a foreign people.

What Calhoun had to say in the Senate:

We have heard much of the reputation which our country has acquired by this war. I acknowledge it to the full amount, as far as the military is concerned. The army has done its duty nobly, and conferred high honours on the country, for which I sincerely thank them; but I apprehend that the reputation acquired does not go beyond this—and that, in other respects, we have lost rather than acquiring reputation by the war. It would seem certain, from all publications abroad, that the Government itself has not gained reputation in the eyes of the world for justice, moderation, or wisdom . . . . and in this view it appears that we have lost abroad, as much in civil and political reputation as we have acquired for our skill and valour in arms. . .

Of the boundary to be drawn at the end of the war:

… it should be such as would deprive Mexico in the smallest possible degree of her resources and her strength; for, in aiming to do justice to ourselves in establishing the line, we ought, in my opinion, to inflict the least possible amount of injury on Mexico. I hold, indeed, that we ought to be just and liberal to her. Not only because size is our neighbour; not only because she is a sister republic; not only because she is emulous now, in the midst of all her difficulties, and has ever been, to imitate our example by establishing a federal republic; not only because she is one of the two great powers on this continent of all the States that have grown out of the provinces formerly belonging to Spain and Portugal—though these are high considerations, which every American ought to feel, and which every generous and sympathetic heart would feel, yet there are others which refer more immediately to ourselves. The course of policy which we ought to pursue in regard to Mexico is one of the greatest problems in our foreign relations. Our true policy, in my opinion, is, not to weaken or humble her; on the contrary, it is our interest to see her strong, and respectable, and capable of sustaining all the relations that ought to exist between independent nations. I hold that there is a mysterious connection between the fate of this country and that of Mexico; so much so, that her independence and capability of sustaining herself are almost as essential to our prosperity, and the maintenance of our institutions, as they are to hers. Mexico is to us the forbidden fruit; the penalty of eating it would be to subject our institutions to political death . . . . When I said that there was a mysterious connection between the fate of our country and that of Mexico, I had reference to the great fact that we stood in such relation to here that we could make no disposition of Mexico, as a subject or conquered nation, that would not prove disastrous to us. . . . you have looked into history, and are too well acquainted with the fatal effects which large provincial possessions have ever had on the institutions of free states—to need any proof to satisfy you how hostile it would be to the institutions of this country, to hold Mexico as a subject province. There is not an example on record of any free state holding a province of the same extent and population, without disastrous consequences.

But before leaving this part of the subject, I must enter my solemn protest, as one of the representatives of a State of this Union, against pledging protection to any government established in Mexico under our countenance or encouragement. It would inevitably be overthrown as soon as our forces are withdrawn; and we would be compelled, in fulfilment of plighted faith, implied or expressed, to return and reinstate such Government in power, to be again overturned and again reinstated, until we should be compelled to take the government into our own hands, just as the English have been compelled to do again and again in Hindostan, under similar circumstances, until it has led to its entire conquest. . . . I must say I am at a loss to see how a free and independent republic can be established in Mexico under the protection and authority of its conquerors. I can readily understand how an aristocracy or a despotic government might be, but how a free republican government can be so established, under such circumstances, is to me incomprehensible. I had always supposed that such a government must be the spontaneous wish of the people; that it must emanate from the hearts of the people, and be supported by their devotion to it, without support from abroad. But it seems that these are antiquated notions—obsolete ideas—and that free popular governments may be made under the authority and protection of a conqueror.

We make a great mistake in supposing all people are capable of self-government. Acting under that impression, many are anxious to force free governments on all the peoples of this continent, and over the world, if they had the power. It has been lately urged in a very respectable quarter, that it is the mission of our country to spread civil and religious liberty over all the globe, and especially over this continent—even by force, if necessary. It is a sad delusion. None but a people advanced to a high state of moral and intellectual excellence are capable, in a civilised condition, of forming and maintaining free governments; and among those who are so advanced, very few indeed have had the good fortune to form constitutions capable of endurance. . . . It is harder to preserve than obtain liberty. After years of prosperity, the tenure by which it is held is too often forgotten; and, I fear, Senators, that such is the case with us. . . . . I have often been struck with the fact, that in the discussions of the great questions in which we are now engaged, relating to the origin and conduct of this war, the effect on free institutions and the liberty of the people have scarce been alluded to, although their bearing in that respect is so direct and disastrous . . . . But now, other topics occupy the attention of Congress and of the country—military glory, extension of the empire, and aggrandizement of the country. . . . We have had so many years of prosperity—passed through so many difficulties and dangers without the loss of liberty—that we begin to think we hold it by right divine from heaven itself. Under this impression, without thinking or reflecting, we plunge into war, contract heavy debts, increase vastly the patronage of the Executive, and indulge in every species of extravagance, without thinking that we expose our liberty to hazard. It is a great and fatal mistake. The day of retribution will come; and when it does, awful will be the reckoning, and heavy the responsibility somewhere.

Calhoun did not believe in an American mission abroad and dreaded the consequences when so many of his fellow countrymen did.

When the war was nearly concluded, Polk asked Congress for authorisation to occupy Yucatan, where the white population was being decimated by war with the Indians. He justified this on humanitarian grounds and by the Monroe Doctrine. The Doctrine was directed against imperialists from beyond the New World, Calhoun said. It had never been intended to justify U.S. intervention in other American countries. He knew whereof he spoke: he was the last surviving member of the Monroe Cabinet which had vetted the doctrine. But his statement, did not, of course, prevent American imperialists later in the century from claiming the contrary.