“Passion governs, and she never governs wisely,” wrote Benjamin Franklin to Joseph Galloway in 1775.[1] Wise words from the wisest of America’s Founders, yet ninety years later the very government that Franklin helped create disregarded his wisdom, fell prey to those very passions, and trampled the constitutional rights of its own citizens in order to help quench what seemed an insatiable thirst for vengeance.

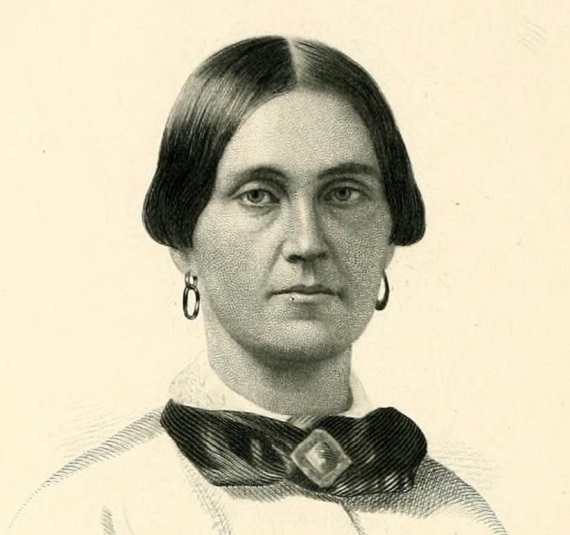

On July 7, 1865, one of those citizens, Mary Elizabeth Jenkins Surratt of Maryland, went to the gallows for her role, or supposed role, in the plot to assassinate President Abraham Lincoln. Though her execution would not have seemed a tragedy to Northerners in 1865, or to many Americans today, it is a glaring example of how government can become tyrannical when given the opportunity, particularly when passions are at a fever pitch, just as Franklin had warned.

As history tells us, Lincoln met his fate at Ford’s Theater on the evening of April 14, 1865, just days after General Lee’s surrender at Appomattox. Euphoric feelings across the North celebrating the end of a long and bloody war quickly abated after news spread that actor John Wilkes Booth had shot the President in the back of the head as he watched a performance of “Our American Cousin.” The injury proved fatal and Lincoln succumbed at 7:22 am on the morning of the 15th. Northerners were now bent on revenge for an act the federal government viewed as the last gasp of the Confederate cause.

Investigating authorities soon discovered a Booth-led plot involving a number of conspirators, including Mary Surratt, who owned a boarding house in Washington City, her son John, and several other men, among whom were Dr. Samuel Mudd, Lewis Powell, David Herold, and George Atzerodt.

All would eventually face the hammer of American justice, in one form or another, for what was proving to be a wide-ranging conspiracy, which included other targets – Secretary of State William H. Seward, who was viciously stabbed multiple times but survived, Vice President Andrew Johnson, whose attacker, Atzerodt, apparently backed out, and perhaps General Ulysses S. Grant, who escaped a possible attack after deciding not to attend the play that night. Killing all four leaders in one fell swoop would have effectively decapitated the US government.

Whether or not Mary Surratt had knowledge of this vast conspiracy, or actively aided in its implementation, will never be known. We can certainly speculate, but beyond mere conjecture the truth remains elusive. However, her actual guilt or innocence matters not. What matters is the manner in which federal authorities obtained a conviction and ultimately her execution.

With Booth dead at the hands of Union troops, the conspirators, all except for John Surratt, were arrested and confined in deplorable conditions, which was not uncommon at the time, to await trial and punishment. John Surratt had evaded capture and was in hiding. He would not be found and brought to trial for another two years.

To aide her cause, Mary Surratt chose a top-notch attorney for her defense team in Senator Reverdy Johnson, a conservative Unionist Democrat from Maryland who had been the nation’s Attorney General under Zachary Taylor and had been a close friend of Lincoln’s, serving as an honorary pallbearer at his funeral. No one could legitimately question his loyalty or patriotism, though the military commission assigned to try Surratt attempted to do just that, but to no avail.[2]

Hoping to gain for Mrs. Surratt a trial in a civilian court, which Senator Johnson felt she was entitled to, his main argument from the start was to attack the validity and constitutionality of the military tribunal, a proceeding that disallowed the basic protections afforded a defendant under normal circumstances, and that he held was a presidential usurpation of power. “To hold otherwise,” he wrote in his 26-page legal argument, “would be to make the Executive the exclusive and conclusive judge of its own powers, and that would be to make that department omnipotent.”[3]

The nation’s new President, Andrew Johnson, who considered Mary Surratt the one who “kept the nest that hatched the egg,” created the commission to try the conspirators but Reverdy Johnson’s argument went much farther than the President’s order and attacked the very foundation of executive military tribunals in peacetime, even though his old friend Lincoln was the first to create these military courts by executive order to deal with massive dissent in the Northern states, which, in nearly every case, was far removed from the war zone.

By 1865, military courts had already dealt with many war-protesting civilians, like Marylander John Merryman, whose 1861 case afforded Chief Justice Roger B. Taney the opportunity to chastise Lincoln for exceeding his authority, and former Ohio Congressman Clement Vallandigham, who was sentenced to prison in 1863 for what amounted to a harsh anti-war speech, only to have Lincoln commute the punishment and banish him to the Confederacy. To make matters much worse, many citizens failed to even get a military trial, as more than 14,400 Northern civilians would be incarcerated without charges or trial under Lincolnian martial law, even though war scarcely touched the North.[4]

And that was precisely Reverdy Johnson’s point. Under the Fifth Amendment, a citizen has a right to a civilian trial with few exceptions, and those exclusions are of a military nature. The first section of the Fifth Amendment reads: “No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the Militia, when in actual service in time of War or public danger….” But according to Johnson’s argument, the exceptions to the Fifth Amendment would include only those persons in actual military service, not civilians, who were also afforded additional legal protection in the Sixth Amendment, he pointed out.

“Can it be that the life of a citizen, however humble, be he soldier or not, depends in any case on the mere will of the President?” he asked in his argument. “And yet it does, if the doctrine be sound. What more dangerous one can be imagined? Crime is defined by law, and is to be tried and punished under the law,” and such trials are to be conducted by judges “selected for legal knowledge, and made independent of Executive power.” But military judges, like those who would preside over the Surratt trial “are not so selected, and so far from being independent, are absolutely dependent on such power.”

As strong as Johnson’s arguments were, passions, and not sound legal judgment, was carrying the day. But he did have strong expert opinions to support his case. Edward Bates, Lincoln’s Attorney General until 1864, believed military commissions were unconstitutional in such situations. Navy Secretary Gideon Welles, who, like Reverdy Johnson, was a conservative Democrat and the only one in Lincoln’s Cabinet, also spoke in favor of a civilian trial for Mrs. Surratt, but he also knew that was unlikely. Welles wrote in his diary that Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, who was in charge of the investigation, wanted “the criminals … tried and executed before President Lincoln was buried.”[5] And that would be impossible in a civilian court. So it was no surprise that the military commission, also the judge of its own powers, denied Reverdy Johnson’s argument.

Perhaps seeing the handwriting on the wall, Johnson turned the bulk of the trial over to his junior associates, Frederick Aiken and John Clampitt, who, in the opinion of many, were inexperienced and not up to the task, although the deck was obviously stacked heavily in favor of the government with the restrictive rules of a military tribunal. The panel of Union military officers serving as judges found Mary Surratt guilty and sentenced her to death by hanging along with the other conspirators.

Before her execution, Reverdy Johnson advised his young colleagues to obtain a writ of habeas corpus and “take her body from the custody of the military authorities. We are now in a state of peace – not war.” This was their last shot to save the life of Mary Surratt. The writ was obtained from Judge Andrew Wylie in Washington, who was apprehensive about signing such an order. He fully understood the passions then running the country and told the two youthful attorneys that his act “may consign me to the Old Capitol Prison.”[6]

But despite the order for Surratt to appear in Judge Wylie’s courtroom, a civilian trial was not to be, as President Andrew Johnson suspended the writ, even though Chief Justice Taney had already ruled the suspension of such writs by a President to be unconstitutional in 1861 in Ex parte Merryman. Lincoln had ignored Taney then and now President Johnson was disregarding Judge Wylie as well as the Merryman decision.[7] The President further ordered General Winfield Scott Hancock to commence with the execution of Mary Surratt, which had already been scheduled for that day, July 7, 1865. Just as Reverdy Johnson feared, justice was solely in the hands of one man and Mary Surratt, by order of the President of the United States, met her fate that afternoon.

In April 1866, nearly a year after the execution, as passions subsided and tempers cooled, the United States Supreme Court ruled unanimously that such military tribunals were unconstitutional. Although Lincoln had appointed five of the Justices, including Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase, the Court held, in the case of Ex parte Milligan, which involved a civilian accused of disloyalty in Indiana, that citizens cannot be tried in a military court when the civilian courts were in operation, as they were in Indiana, just as they had been in Maryland the year before.

Writing the Court’s sole opinion was Justice David Davis, who had been Candidate Lincoln’s campaign manager in 1860 and President Lincoln’s choice for the Court in 1862, but despite his ties to the now martyred chief, he lambasted the government for trying civilians in military courts, an action he said was wrought with danger. “It is the birthright of every American citizen when charged with crime, to be tried and punished according to law,” he wrote. “By the protection of the law human rights are secured; withdraw that protection, and they are at the mercy of wicked rulers, or the clamor of an excited people,” the same dangerous passions that Dr. Franklin had warned about. “Civil liberty and this kind of martial law cannot endure together; the antagonism is irreconcilable; and, in the conflict, one or the other must perish.”[8]

Thinking far into the future, Justice Davis warned posterity of the dangers that could lie ahead if the nation did not learn the lessons of the late war. “This nation, as experience has proved, cannot always remain at peace, and has no right to expect that it will always have wise and humane rulers, sincerely attached to the principles of the Constitution. Wicked men, ambitious of power, with hatred of liberty and contempt of law, may fill the place once occupied by Washington and Lincoln; and if this right is conceded, and the calamities of war again befall us, the dangers to human liberty are frightful to contemplate.”

But sadly the Court’s historic ruling came too late to save Mary Surratt, whose conviction would have been highly unlikely has she been afforded the basic criminal protections in a civilian trial. We can surmise this based on the fact that John Surratt, whose involvement was likely deeper than anything his mother had been accused of, escaped punishment when a jury in a civilian court failed to reach a verdict in his trial in 1867. Prosecutors decided against a retrial, so John Surratt was saved from the same fate as his mother by the sound judgment of Milligan. The New York Times recognized the sole reason why. “John H. Surratt was called to his account in a calmer state of the public mind, after time had appeased its righteous anger and the passion for retribution had been allayed.”[9]

As Thomas R. Turner has written of the Surratt trials, “The major difference was not the legal context of the two trials, but that, two years after the assassination and the end of the Civil War, people were much more willing to judge the evidence in a rational manner.” With the result of John Surratt’s trial, it “was thus easy to make the case that an enlightened civil jury had rendered a fair verdict while the military commission’s verdict was a horrible miscarriage of justice that sent some innocent persons to their deaths.” But a “closer examination of the facts reveals that such a view is simplistic and misleading.”[10]

Such an explanation, though, is neither simplistic nor misleading, for the “legal context” of the trials, in addition to the passions of the day, made all the difference for John Surratt. Had Mary Surratt been tried in a civilian court, it is quite likely she would have escaped the hangman’s noose and lived to a ripe old age. Of that we can only speculate. Perhaps she was truly guilty of everything she was accused of, but it should have been a civilian court that proved her guilt beyond a reasonable doubt, not a committee of military generals in a tribunal without a presumption of innocence for the accused, adequate time to prepare a defense, and normal rules of evidence.

But as the Mary Surratt trial demonstrated, and Hollywood[11] brought to the big screen for the entire world to see, passion and raw emotion, if left unchecked, is the gateway to tyranny. And, as history has shown, tyrants care nothing for the law or the Constitution. The “trial” and execution of Mary Surratt was never about healing a broken-hearted nation but an effort to destroy the last vestige of the Southern rebellion, to bury the Confederacy, and all memories of it, once and for all, and to ensure the South never again threatened the supremacy of the Union.

As Cicero once said, “In times of war, the law falls silent.” Tragically, the case of Mary Surratt proved that beyond a shadow of a doubt.

[1] Benjamin Franklin to Joseph Galloway, February 5, 1775, in The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, Volume 22, page 468 – located at www.franklinpapers.org.

[2] Bernard C. Steiner, Life of Reverdy Johnson (Baltimore, 1914).

[3] Reverdy Johnson, “Argument on the Jurisdiction of the Military Commission,” June 16, 1865. This document, along with the trial transcripts and other relevant trial documents, can be found at www.surrattmuseum.org.

[4] This figure was compiled by Mark E. Neely, Jr. in his book The Fate of Liberty: Abraham Lincoln and Civil Liberties (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992). Also see his article in The Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association – “The Lincoln Administration and Arbitrary Arrests: A Reconsideration” – http://quod.lib.umich.edu/j/jala/2629860.0005.103/–lincoln-administration-and-arbitrary-arrests?rgn=main;view=fulltext.

[5] Diary Entry, May 9, 1865, Diary of Gideon Welles (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1901), Volume 2, page 303.

[6] Kate Clifford Larson, The Assassins Accomplice: Mary Surratt and the Plot to Kill Abraham Lincoln (New York: Basic Books, 2008), 206-207.

[7] For more on the Merryman case, see Jonathan W. White, Abraham Lincoln and Treason in the Civil War: The Trials of John Merryman (Baton Rouge, 2011) & Brian McGinty, The Body of John Merryman: Abraham Lincoln and the Suspension of Habeas Corpus (Harvard, 2011).

[8] Ex parte Milligan, 71 U.S. 2 (1866). Interestingly, one of Milligan’s lawyers was James A. Garfield, the future President. Arguing the case for the government was Benjamin “Beast” Butler.

[9] New York Times, August 12, 1867.

[10] Thomas R. Turner, “What Type of Trial? A Civilian Versus a Military Trial for the Lincoln Conspirators,” The Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association – http://quod.lib.umich.edu/j/jala/2629860.0004.104/–what-type-of-trial-a-civil-versus-a-military-trial-for?rgn=main;view=fulltext.