A review of Southern Horizons: The Autobiography of Thomas Dixon (IWV Publishing, 1994).

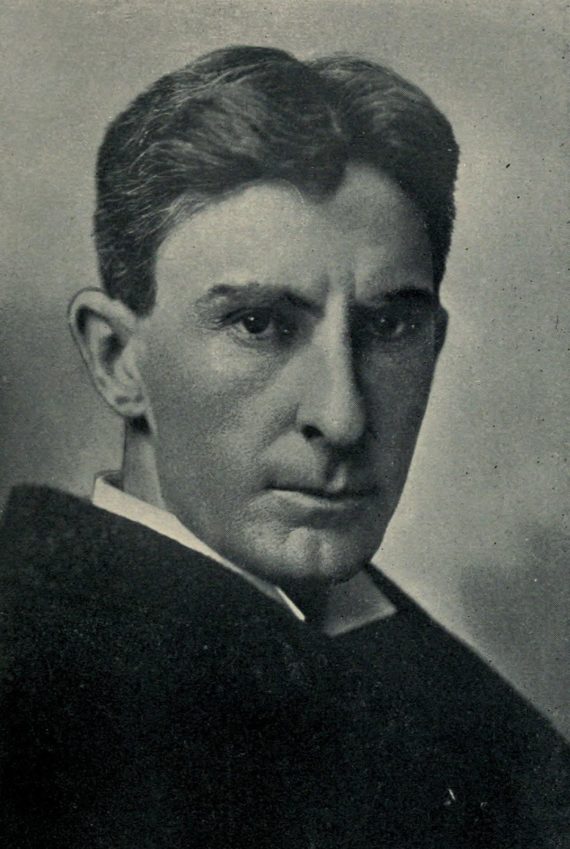

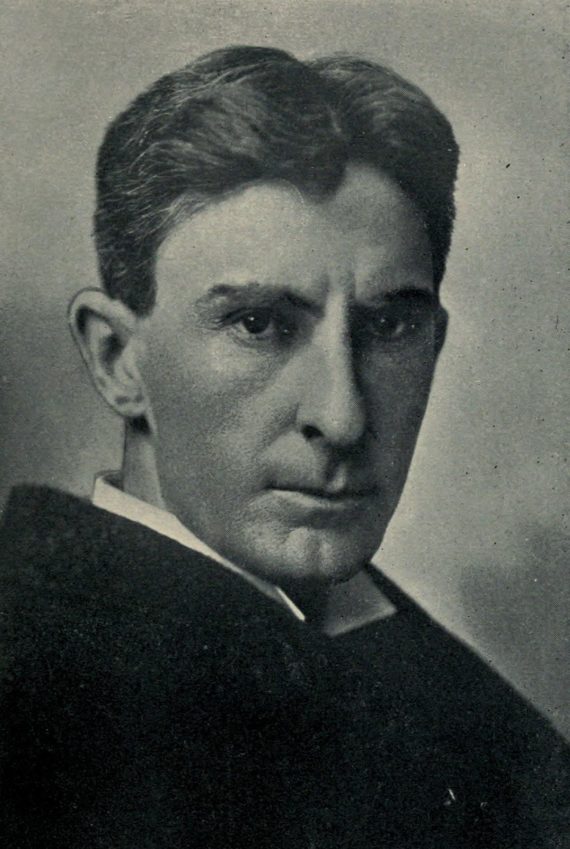

The name of Thomas Dixon today is little remembered, North or South, but seventy years ago Dixon was one of the most prominent and controversial public figures in the country. The discovery and publication of his autobiography ought to be considered a significant event in the cultural history of the United States. After all, Dixon was the chief collaborator of David Wark Griffith in the production of the epic motion picture “The Birth of a Nation,” and the author of the novel on which it was based, The Clansman. For that reason, if for no other, Dixon deserves a niche in the nation’s memory. But the autobiography offers much more than that, for Dixon’s principal contribution in it is his eyewitness account of the terror of the Reconstruction period, an account that needs to be set against revisionist tamperings with what used to be called “the tragic era.”

Let it be said at the outset that this is a very uneven book; but then, Dixon’s was a very uneven life. He was a bundle of contradictions and he still resists classification, a far more complex man than an earlier generation may have thought. The bare outline of his life and career contains so many startling surprises and reverses that it would be thought too fantastic even as fiction, were it not documented.

Dixon was born near Shelby, North Carolina, in the first days of 1864. His father, a farmer, merchant, and Baptist minister, was a man already in his fifties, too old to fight for the Confederacy, then in the waning months of its fitful life. Dixon’s childhood was passed in the poverty, sorrow, terror, and anger of Reconstruction. An adolescent before he began his formal education, Dixon took quickly to his studies and obtained a Master of Arts degree from Wake Forest College at age nineteen. He spent a semester in a graduate program at Johns Hopkins University, then journeyed to New York to dabble briefly in acting. Dissatisfied, he returned to North Carolina to study law. Before finishing his legal education, and while still under the legal age, he was elected to the North Carolina legislature.

By 1886, Dixon was a twenty-two year old newlywed, a practicing lawyer, and a state legislator. A political career, in which he might redress the wrongs done the South by the Radicals, seemed to beckon. Yet he was still restless. In the autumn of that year, he resolved his inner tensions by resigning from the legislature and entering the Baptist ministry, fulfilling a wish of his father. After brief pastorates at Goldsboro and Raleigh in his home state, he found his way north once again, first to a Baptist pulpit in Boston, then to a pastoral appointment at the Twenty-Third Street Baptist Church in New York. In the metropolis, Dixon, never known for modesty or thinking small, began to dream truly grand designs. So that his audience could expand beyond one congregation of one denomination, he conceived of a non-denominational “People’s Church,” housed in its own commercial-office building and offering a wide range of social outreach programs to the city’s teeming millions. He boldly approached John D. Rockefeller, Sr., and gained the backing of “the Oil King” for his idea. But the jealousy and obstruction of rival ministers frustrated his plan, and it never came to fruition. Also while in New York, Dixon tackled the Tammany machine; both sides notched some victories in their mismatched war.

About the turn of the century, overwork forced Dixon to give up his regular ministry for the lecture circuit. He moved his family to a gracious manor house in Virginia’s Tidewater region and began dividing his time and considerable energies between his lucrative lecturing and a new project which he considered his life’s work. For some years, Dixon had mulled over the idea of telling the South’s side of the story of Reconstruction in a set of historical novels. He now could pursue his goal in earnest, and the first of the series, The Leopard’s Spots, appeared in 1902.

For the next quarter century and more, Dixon was very much a public man: best-selling author, successful dramatist, sometime actor, and writer, producer, and director of several motion pictures. He accomplished his object of gaining the South a sympathetic hearing, but dissipated his energies on various topical issues of the day. He made and lost several fortunes, until, by the time of the crash of 1929, there were no more fortunes to be made. Dixon was still able to get his writings published, and in the first term of Franklin D. Roosevelt he was an enthusiastic New Dealer, touring the South giving speeches to promote the National Recovery Administration. By 1936, he had begun to have doubts. In the summer of that year, Dixon was a delegate to the Democratic National Convention; but in the fall he campaigned for the Republican candidate, Alf Landon. Landon lost, of course, but Dixon’s services were rewarded by a Republican judge, who gave him the patronage appointment as clerk of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of North Carolina.

After the death of his wife of fifty-one years, Dixon remarried at seventy-five. The second Mrs. Dixon, Madelyn Donovan, was a former film actress who had been Dixon’s researcher, collaborator, and Girl Friday for many years before their marriage. She now performed most of the duties of his court clerkship for him, until his declining health finally forced him to resign in 1943. Dixon lingered in obscurity and near poverty until his death in the spring of 1946. Madelyn Dixon zealously protected his memory until her own death in 1975.

Such was the crowded life of Thomas Dixon, its sunny peaks and its dark valleys. But, as has been said, the chief value of Southern Horizons for present-day readers is in its provision of a vivid first-hand account of Reconstruction, a time Dixon remembered as a nightmare of lawlessness, injustice, and oppression visited on the people of the South by their own nominal national government in Washington. The scenes described here are not for the squeamish, and the blunt language may be shocking to fastidious twentieth century minds, but there can be no doubt of the passion that drove Dixon to preserve this tale of outrage for succeeding generations. Many Americans today, in this age of historical amnesia, would disbelieve that one part of their country was once put under military occupation by another part, that heinous crimes went unpunished, that summary arrests and summary executions were common, that courts were subverted, legislatures corrupted, and the majority of the electorate disfranchised — all at the instance of the federal government!

The chief villain of the piece is Thaddeus Stevens, leader of the Radical forces in Congress and fervent hater of the South. The suffering Southerners of the period were clear on the point that Congress was responsible for their torment and the orgy of corruption and misgovernment their states had endured. Indeed, when Dixon was at Wake Forest College, the students called the six-hole privy on campus the “Sixth Congressional District,” while the five-holer was known as the “Fifth Congressional District.”

Because, as do Dixon’s Reconstruction novels, the autobiography deals at some length with the activities of the Ku Klux Kian, an explanatory note is in order. Most readers of this review will be aware that the original organization of that name has no connection with the contemporary gang of social misfits and small-time thugs which today disgraces the flags, Stars and Stripes as well as Stars and Bars. But an earlier generation, before the rise of the present-day Kian, had a clearer remembrance of the reality of Reconstruction. That generation included such men as Woodrow Wilson, born in Virginia in 1856 and reared in Carolina and Georgia, who as President was persuaded to have a White House screening of “The Birth of a Nation” for his cabinet and who described the film as “history written with lightning.” It also included Edward Douglas White, Chief Justice of the United States, whose aid Dixon also enlisted in overcoming the opposition of would-be censors to the film, and who, as a young man in New Orleans had himself shouldered a rifle as a Kian sentinel when the helpless citizenry could not rely on the alien government for the protections of the law. But Dixon freely admits that the Kian passed very early from the control of its leaders and became frequently as much a hindrance as a help in the restoration of order. In Dixon’s own county, the Kian, led by his beloved uncle, Colonel Leroy McAfee, sprang up in response to a grisly rape that the Carpetbag officials proposed to let go unpunished. But even so strong a leader and honorable a man as Colonel McAfee could only with difficulty keep the lower elements in his organization from turning from the punishment of crime to the settling of private scores.

At his best, Dixon was no more than patronizing in his attitude toward blacks. Yet there are several black characters in Southern Horizons who are treated relatively sensitively. There is Aunt Barbara, Dixon’s saintly nurse, so steeped in Biblical idiom and cadence that it was her everyday speech. There is Dick, an engaging rapscallion, the companion of Dixon’s youth. There is Nelse, loyal servant of Dixon’s grandmother, who threw a hatchet at the officious Freedmen’s Bureau agent who tried to cajole him into leaving his old mistress. And there is this inspiring story of the loyalty of Dixon’s father’s slaves: In 1863, a few months before Dixon’s birth, the elder Dixon sold a plantation in Arkansas and determined to move his family back to Carolina. He had declined an offer of $100,000 in gold for the slaves, feeling a responsibility for their welfare. For the trek east, some of the slaves were mounted and armed and entrusted for safekeeping with shares of the gold from the sale of the plantation. Passing through territory traversed by Union armies, they had every opportunity and incentive to leave, yet they performed all the tasks assigned them and saw the family safely to the old home in Carolina.

It must not be supposed that Dixon was a partisan of the “Old” South. He was a “New” South booster, deprecating farm life and favoring industrial development. He considered himself thoroughly modern and up-to-date and he displayed a distressing tendency to bend in the breeze of all the pseudo-progressive “isms” of his day. One suspects as well that whatever record he has left of his theological thought should not be examined too closely for the consistency of its orthodoxy. Dixon always proclaimed his high regard for Lincoln — and for Eugene V. Debs. He held Theodore Roosevelt in esteem for his reform work in New York; “TR” was the first Republican Dixon ever voted for, after quite an ordeal of conscience. He rejoiced that there came another Roosevelt — a Democrat — for whom he could vote more naturally.

Dixon had a fairly wide acquaintance among famous people, and was not shy about using his contacts for advantage. He got John D. Rockefeller, Sr., to support his church-building plans in New York City. He called on his fellow North Carolinian Walter Hines Page for aid in publishing his first novel. And he turned to the President of the United States, Woodrow Wilson, for help in gaining an audience for “The Birth of a Nation,” confident that Wilson would remember that Dixon had been instrumental in getting him an honorary degree from Wake Forest College when they both were young men.

Southern Horizons is of uneven literary quality, yet there are memorable, colorful episodes on almost every page. With her pipe and toddy close at hand, Dixon’s nonagenarian grandmother spins tales of the Revolution — the one that succeeded. There is a poignant story of Dixon’s first puppy love. A wilful young Dixon experiences fierce conflicts with his father. A Boston hotel refuses to allow Dixon and his family to register with their black nurse. A thrifty old gentleman, wary of unsound money from bitter experience, makes a loan to his pastor, asking to be repaid in bills and coins of the same denomination as each of these he is parting with. There are long, lyrical passages on Dixon’s sporting life in Tidewater, Virginia, and hilarious glimpses of what once passed for “advanced thought.”

The reader should be warned that this book has come from the hands of editors who, although they are to be commended for patching together a coherent text, felt compelled to add somewhat irrelevant prefatory notes and off-the-point appendices seeking to set Dixon in his context — that is, to explain away his fixation on the wrongs of Reconstruction. But that fixation is precisely why this book should be read by those who would understand the extraordinary solidarity and cohesion of the South in the decades following Appomattox. Southerners had come through a hellish experience and were determined that it should not recur. It is a lesson and a warning that, ominously, is increasing in relevance today.