A review of I’ll Take My Stand by Twelve Southerners (LSU, 2006).

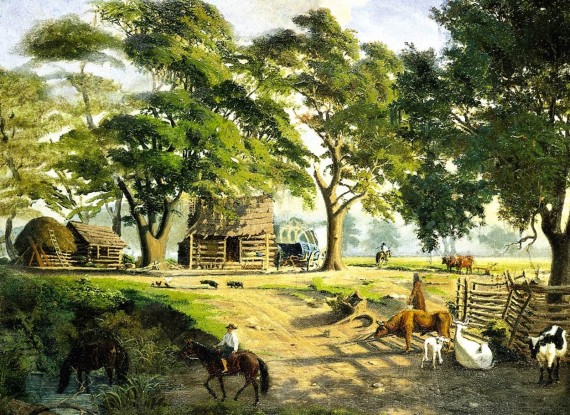

In this age where the homogenization of our culture is nearly complete, thanks largely to widespread media and rampant industrialism, I’ll Take My Stand remains as fresh and relevant as the day it was published more than seventy years ago. Instead of indulging in reactionary daydreams or nostalgia, as some of the book’s less perceptive critics have claimed, the Twelve Southerners marshalled all their intellectual and literary powers to defend a way of life, rooted in the land and in the customs of small town living, that was very much in evidence prior to the War for Southern Independence and which really provided the anchor for the freedoms and liberties Americans enjoyed up to that time. Their criticisms circa 1930 have proven frighteningly prescient for our own times in which any individuality we might have as separate regions of a great nation have been almost entirely swallowed by mass production, mass culture, and centralized government.

There are some truly astonishing pieces here, all forthright, honest, and so logically argued they are hard to refute. Among them I would cite Ransom’s opening “Reconstructed but Unregenerate”, Owsley’s “The Irrepressible Conflict”, and Lytle’s “The Hind Tit.” Most impressive of all is John Donald Wade’s beautiful “The Life and Death of Cousin Lucius”, really a novel encapsulated into little more than thirty pages, in which the Agrarian ideal is exemplified in the life (and death) of one simple Georgia farmer. Other essays I find less satisfactory if not downright obtuse – Tate’s “Remarks on the Southern Religion” (disappointing and inconclusive by his normally high standards) and Stark Young’s rather coy “Not in Memoriam, But in Defense.” But even the lesser essays leave one much to think about and ponder over and worry about.

You can scoff at the Twelve Southerners and consign them to the intellectual dustbin as daydreaming rednecks and mossbacks, but you do so at your own peril. In any event they should be read before they are condemned. And I predict they will be read a hundred years from now and beyond, so long as there are people concerned about the state of their communities, their liberties, and their own souls.