A review of A Thousand Points of Truth: The History and Humanity of Col. John Singleton Mosby in Newsprint (ExLibris, 2016) by V.P. Hughes

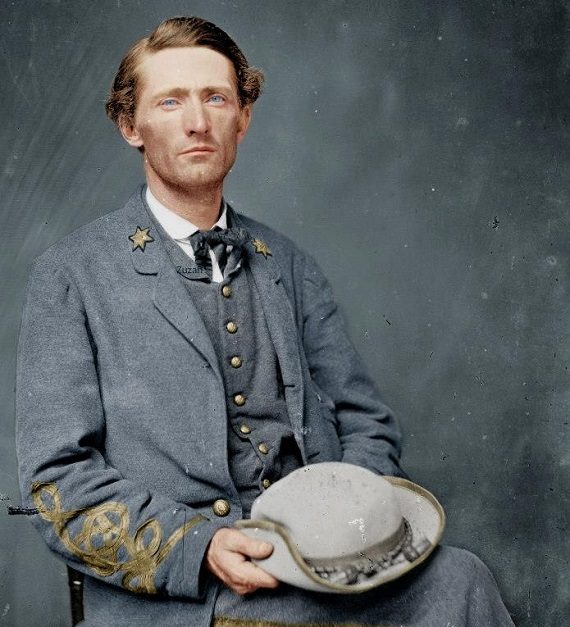

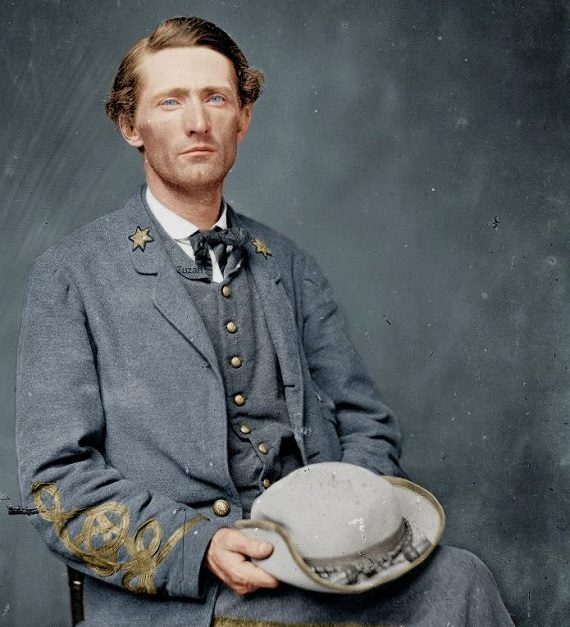

Valerie Protopapas (who writes under her maiden name V.P. Hughes) has given us a massive work on Confederate guerilla fighter, Colonel John Singleton Mosby (1833-1916). Her tome, which reaches over eight-hundred pages, is made up of annotated newspaper reports about her subject spanning a lifetime that ended with his death more than fifty five years after the War Between the States. Mrs. Protopapas leaves no doubt about why she undertook her task and states it unabashedly in the introduction: “I hope to show that John Singleton Mosby was a true hero who struggled not just against the armed might of a powerful enemy, but against the forces of political, moral and ethical chaos that raged around him in his well-considered life.”

The author’s involvement with Mosby often seems to border on adoration; and the fact that she has spent most of her life on Long Island makes this attraction all the more interesting. Whenever she quotes Yankee newspaper editors raging against Mosby’s alleged “atrocities” as a guerilla leader in North Central Virginia, she rushes almost indignantly to his defense. And she appears genuinely relieved that after the defeat of the Confederacy, demands by vengeful Union supporters for Mosby’s imprisonment and execution never lead to any action, other than a few short-term detainments that ended in his release.

From newspaper comments, it seems that the guerilla tactics of the man known as “the Gray Ghost”, which entailed capturing Union commanders with small bands of irregulars, aroused admiration on the victorious side as well in the South. Moreover, right after the War, Mosby became an admired tactician across the ocean, and Prussian Chancellor Otto von Bismarck encouraged German officers to study his remarkable form of warfare. Perhaps more than any other connection, his contacts with Union General Ulysses S. Grant helped extricate Mosby from difficult situations for several years after the War. Grant conferred on Mosby a safe conduct pass when the two met in January 1866 that served the “Gray Ghost” in good stead, until his enemies lost their passion for revenge.

Mosby’s relation to Grant yielded other benefits. He joined the Republican Party while Grant was preparing to run for a second term in 1872, and the general who gave him a handwritten letter of safe passage later became his lifelong friend. In 1876, Mosby, by then widowed, relocated to Washington, and tried to gain access to Grant’s successor, Rutherford B. Hayes. What other Southerners, including Mosby’s neighbors in Warrenton, Virginia, viewed as opportunistic moves caused his popularity to plummet among zealous defenders of the Confederate cause. Here Mrs. Protopapas comes to Mosby’s defense. His support for Grant and his decision to join the national Republicans was intended to bridge the gap between Republicans and Southern Democrats. In Virginia Mosby withheld support from pro-Reconstruction Radical Republicans and backed the state Conservative Party and their gubernatorial candidate in 1873 General James Kemper. Mosby’s strategy was to establish cooperation between the Conservatives in Virginia (who were formed out of and then returned to the Southern Democrats) and Grant and the national Republican leadership.

Although Mosby benefited from this arrangement professionally, he was also pursuing, according to Mrs. Protopapas, his own form of Southern strategy. The “white Virginians” to whom the Conservatives appealed held very little power during Reconstruction. Their region had been occupied by enemy armies, and many former Confederate soldiers were still disenfranchised. The best hope they had for regaining control of their state, as Mosby understood, was splitting the victorious side represented by the Republican Party. In 1873 Mosby was still at most a tentative Republican, even after he had acted as Grant’s successful campaign manager in Virginia. By then, however, he had become a confidant of his onetime adversary and played a role in Grant’s decision to approve a general amnesty for all Confederates.

There are possibly three reasons that Grant showed favor to Mosby so soon after the war was over. In 1864 he narrowly escaped being shot by Mosby’s Raiders as he rode through North Central Virginia unescorted. Perhaps Grant attributed his good fortune to Mosby’s decision to spare him. Moreover, like many others of his generation and like Mrs. Protopapas and this reviewer, the Union commander may have been awed by Mosby’s military prowess. Considering that he was educated in Classics at the University of Virginia and was a notably poor math student, his talent as a guerilla commander seem all the more remarkable. It should also be noted that once Lee surrendered in Virginia and Joe Johnston outside of Durham, North Carolina, Mosby made clear to his troops that the war was over. Grant recognized that this daring commander would not be inclined to resume hostilities.

Mrs. Protopapas indicates that she “took up the cudgels” for Mosby after reading a biography about him published by Virgil Carrington Jones in 1944. Jones gives the impression that his subject’s long life after the War Between the States damaged his reputation and that “from the perspective of his fame,” he would have done better to have died while the war was still raging. According to our author, this view of Mosby’s “post-war life demonstrated a strong taint of the revulsion found in the minds of the man’s fellow-Southerners past and present.” It suggests that Mosby did little of value between 1865 and 1916 “in comparison to the worldly fame he might have achieved by dying at the hands of his enemies in 1864.” What A Thousand Points of Truth amply demonstrates is that Mosby’s earthly existence was punctuated by many phases, a reality that is not gainsaid by his fellow-residents of Warrenton who burnt down his house in anger when he left for Washington.

Among Mosby’s post-war positions were acting as consul in Hong Kong, working as a railroad lawyer for the railroad tycoon Leland Stanford, and serving as an attorney in the Department of Justice. Toward the end of his life he composed his war memoirs, in which his superior in the Confederate cavalry JEB Stuart is prominently featured. Up until the last months of his life, as Mrs. Protopapas shows, Mosby went on commenting not only on the Lost Cause but also on current events. He never engaged in exaggeration or self-praise in describing the cause he had served. Further, Mosby was aware of heroism on both sides of the war, and for many years he had friends who had worn blue as well as gray.

For those who are not old enough to remember, Mosby was once a widely revered nineteenth century American hero, like Davy Crockett and Andrew Jackson. The “Gray Ghost” was featured in a popular TV series in the 1950s; and young Americans, like me, grew up properly recognizing in Mosby a noble and manly epic figure. (Of course he was that and more.) Mosby was also, like Lee, a figure who personified reconciliation in post-Civil War America and who illustrated the possibility that the victorious North and its defeated Southern fellow-Americans could honor heroes on both sides of a tragic struggle. That America is now dead, destroyed by antifascist vandals, PC administrators and would-be educators. In this new and less admirable America Mrs. Protopapas’s subject has no place of honor.