In what became the United States, servitude of people of the black African race existed for about two and a half centuries. The subject of American slavery is today so entertwined with unhealthy and present-centered emotions and motives—guilt, shame, hypocricy, projection, prurient imagination, propaganda, vengeance, extortion—as to defy rational historical discussion. Curiously, the much longer flourishing of African bondage—in the Caribbean and South America, in Africa itself, and in the Muslim world—seldom enters into American consciousness.

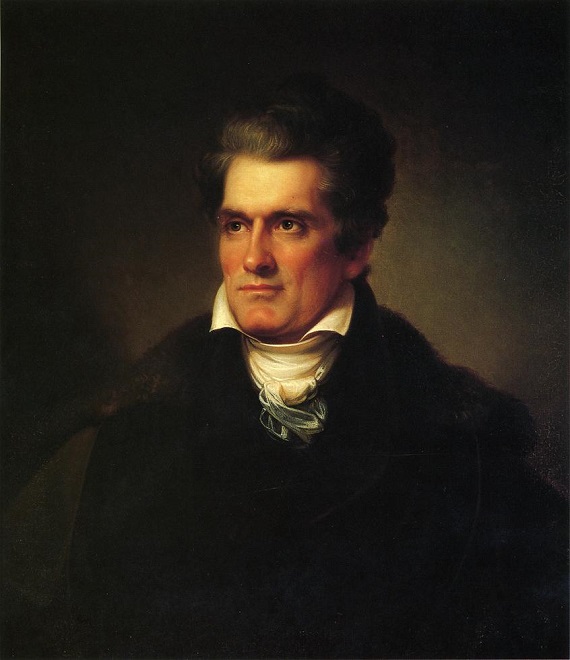

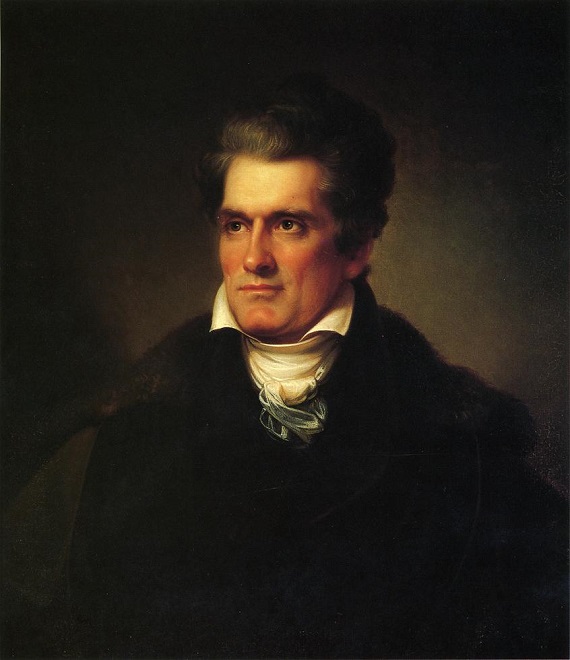

It is appropriate therefore to commence the understanding of this critical part of American history with an investigation of the antislavery movement. There will come a time, perhaps, when it will be necessary and possible to examine American slavery itself in order to appreciate fully what Calhoun meant when, in a speech in the Senate on February 6, 1837, he used the words “positive good” to describe the long-established institution of domestic slavery in his Southern society.

In undertaking to put Calhoun in the right context I will try to succinctly describe the abolitionist movement that arose in the 1830s, which was the cause and immediate occasion for Calhoun’s famous statement. Prior to the outbreak of the new abolitionism, antislavery sentiment had been widespread. Slavery’s economic and political defects, real and imagined, were freely discussed and gentle Quakers went about the business of promoting individual emancipation. Indeed, in the early 19th century one of my North Carolina ancestors freed his few slaves as a matter of conscience.

It was Calhoun’s purpose to call attention to the changed nature of antislavery and what that meant for the American future. To make a long story short, this new anti-slavery campaign was a crusade of evangelistic Christian heresy bent on purging the world of other people’s sins. It repudiated friendly persuasion and preached hatred of the slave-owner, indeed of all Southern society, in truly vile terms of abuse. According to the new abolitionism of the 1830s in sermons, press, and voluminus petititons to Congress, the South was a House of Horror inhabited by depraved whites and tortured blacks. Slavery was a sin to be purged immediately and without any attention to practical details.

A lurid imaginary conception of slavery rather than the everyday reality of life in the South, about which most knew nothing, energized the abolitionists. Little attention was paid to the actual welfare and future of the black people, who appear mostly as suffering victims in a melodrama and humble recipients of Northern benevolence. It is often difficult to tell whether the abolitionists most feared slavery or the presence of black people. By the late antebellum period, New England’s premier intellectual, Waldo Emerson, was predicting approvingly that the blacks, when free and deprived of the paternal care of the Southern whites they had irreparably corrupted, would soon die away and be as extinct as the dodo, leaving America to the pure Anglo-Saxon.

In the context we should make clear that the fanatical temper of this new mass movement alarmed not only Southerners but most of the orthodox Christian clergy and the general citizenry of the North. Also, that it was not a North-wide phenomenon, but was centered in areas settled by the poorer class of New Englanders. These regions, especially Vermont, western New York, and parts of the Midwest, were widely recognised as the source of other strange “isms” as well as abolition—of Mormonism, Seventh Day Adventism, spiritualism, prohibitionism, Anti-Masonism, vegetarianism, feminism, and free-love-ism among others. The outbreak of reformist zeal had more to do with the internal religious and social tensions and the breakdown of Calvinist orthodoxy within this specific greater New England culture region than with Southern realities. The tensions and unrest were projected outward, in honoured puritan fashion, towards the sins of others. This same region furnished John Brown with the financial backers and accomplices for his expeditions. A lower class phenomenon, this zeal yet comported well in its thrust with the Transcedentalism that was attracting New England intellectuals.

One could make several large books just studying the Northern condemnation of what was deemed the fanatical and meddling spirit of New Englanders. A prominent New York Democratic writer said:

The Abolitionists have throughout committed the fatal mistake of urging a purely moral cause by means, not only foreign to that character, but hostile to it, incompatible with it. Where they had to persuade, they have undertaken to force. Where love was the spirit in which they should have approached the task, they have done it in that of hate.

It becomes evident to anyone on close examination, although Calhoun did not mention this aspect, that abolitionist propaganda was a form of pornography, dwelling on the possibilities of sexual license in the master/slave relationship. The great abolitionist preacher Henry Ward Beecher, brother of Mrs. Stowe of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” fame, made money by selling tickets to pretend slave auctions featuring young, almost-white women for sale.

The abolitionist mindset has long dominated American history and absorbed Calhoun’s defense of slavery into its own telling of the American story. A common, widely accepted history of American anti-slavery goes something like this:

Negro slavery was an unfortunate relic of colonialism. Our all-wise Founding Fathers, including the great statesmen from the South, intended to put it on the road to extinction. After all, in 1776 they declared to the world that “All Men Are Created Equal,” in 1785 they banned slaves from the vast unsettled territory North and West of the Ohio River, and they continued thereafter to speak of slavery as undesirable. In this account it is not always mentioned that opposition to slavery was mostly theoretical was usually linked with impractical notions about the removal of the emancipated blacks from the midst of American society.

Then, according to the conventional account, something terrible happened that changed the course of history. The cotton gin made slavery once more profitable. Southerners, through their greed (from which Northerners seem to have been free), reversed the intentions of the Founders and begin to cling to and defend their awful institution from the criticism of benevolent, enlightened, and progressive Northerners. If not for this unfortunate invention, slavery would have dwindled away.

Then, in 1832 South Carolina, driven to treason by its hysterical devotion to slavery, invented States rights and nullified the tariff. This action was illegal, unconstitutional, unprecedented, based entirely on a fraudulent version of the Constitution, intended to break up the Union, and was a blow struck at the prosperity and progress of all true Americans.

But, as the story goes, this was only the prelude to a long treasonous conspiracy of the “Slave Power.” The Slave Power was imagined as a ruthless, violent class of large slave-holders who kept the blacks and most of the whites of the South in ignorance, poverty, and subjection, imperiously and selfishly ruled the Union, and in its arrogance even designed to spread slavery to the virtuous North. It was the implacable enemy of Northern rights and American values.

The Slave Power conspiracy took a decisive step forward in 1837, when the evil genius John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, in another turning point in history, declared that slavery was not an unfortunate evil but a desirable thing, a “positive good.” Calhoun, of course, was motivated by bitter spite from having been thwarted in his insatiable ambition to become President. Thereafter, he and his disciples laboured unceasingly to spread the scourge of slavery and to rule or ruin the United States.

The conspiracy of the slave-holding elite reached its height with secession. In its wickedness and folly the Slave Power sought to destroy government of, by, and for the people. Southerners engaged in rebellion against the best government on earth and rejected the saintly Lincoln, who had been chosen by the people and by God to lead the country through its greatest crisis. Only those perverted by slavery could have made such a diabolical attempt to destroy the United States, the last best hope of mankind.

Inevitably, the wicked rebellion instigated by the Slave Power was defeated by the forces of righteousness, and the Great Emancipator, in the noblest act in history, struck the chains from enslaved black people and made them forever free, something which he had longed for piously from his youth. The earlier version of the tale featured adoring blacks at the feet of noble emancipators like Lincoln and Robert Gould Shaw. A revised version pictures noble self-emancipated blacks and noble boys in blue rushing into each other’s arms to overthrow the brutal Southern masters. Neither version gives a remotely truthful perspective on what actually happened during the catastrophic blood-letting of 1861- 1865.

This scenario is widely believed and may be the interpretation of the Civil War era held by the largest number of Americans. As an account of American history it is false in every particular. It is a fairy tale made up to sustain the notion that America, except for the South, is uniquely virtuous among the nations and always motivated by high and benevolent ideals. It covers with righteousness and inevitability the brutal war of conquest, domination, and exploitation that was waged against the Southern people from 1861 to 1876. It is the rehashed propaganda of one side in a vast and complex conflict, not the sober judgment of history. We feel its power when George W. Bush talks about an American mission to spread virtue throughout the world, no matter how many ungrateful people have to be killed. He is heir to the abolitionist playbook which tells us that America, democracy, and Christianity are endowed with a mission to purify the world of evil.

This was the predominant mode of telling American history before the 20th century, though in published works it appeared in a more circumstantial and sophisticated form. In order to understand the propagandistic misrepresentation of Calhoun we need to see where the fairy tale fudges the truth.

In the first half of the 20th century the evil South interpretation of the Civil War was questioned and altered to a considerable extent by professional historians who were trained to examine primary sources exhaustively and skeptically. Their inclination was to look at both sides of a controversy in search of a larger truth rather than view the past as a story of good guys and bad guys. These historians were also disillusioned by the moralistic righteousness that had justified the catastrophic and fruitless death toll of the Great War. Further, they were willing, while unsympathetic to the South, to perceive the self-interest that marked the North in the sectional controversy. And were not persuaded that the Big Business empire created by the Northern victory was altogether a wonderful thing.

The premier American historian, Charles A. Beard, wrote that the Civil War war was not a civil war and not about slavery, but was a clash between the ruling classes of two regions with competing economic interests. Other historians were not afraid to describe the irrational nature of abolitionism and to discover that opposition to slavery was not necessarily motivated by benevolence toward the slave. And some historians saw the conflict not as inevitable but as resulting from extremism and blunders by political leaders of both sides that brought about a crisis that no sensible person wanted. As one scholar has put it, The War was about “an imaginary Negro in an impossible place.”

In our time the fairy tale interpretation of The War has come back with a vengeance. It is reflected in the much hyped TV series by Ken Burns and in the most sophisticated and celebrated histories of the day. There is not time to go into the interesting question of why this is so, but, despite claims to the contrary, it has absolutely nothing to do with actual historical knowledge and expertise having reached a higher truth. Having engaged in a good many arguments over the years, I have realised that the propagators of this view are often guilty of extreme lack of actual knowledge about the events and conditions of 19th century America. I know of a graduate student who in a paper mentioned Jefferson’s and Madison’s strong allegiance to state rights. A tenured full professor of American history told the student that he had made it up—it couldn’t be true. This “scholar” knew what he had been taught, that State rights was something invented out of the air by John C. Calhoun in the cause of slavery. Much of the present insistence that an evil Southern defense of slavery is the complete explanation for the war of 1861–1865 rests on this kind of ignorant adherence to fashionable dogma.

The fairy tale now takes the form of a hardened Cultural Marxist party line. Revolutionary change is always good and those who oppose it always evil. The only significance of the war is that it was a destruction of the Southern ruling class through the ongoing dialectic of revolution. The only thing to be regretted is that more recalcitrant Southerners were not killed and even greater revolutionary change was not forced upon American society. Differing interpretations are heresies to be suppressed, not arguments to be answered. They are damned as “revisionism.” Revisionism used to mean simply a revised historical interpretation, something harmless that occurred naturally every once in a while. It is now a term of abuse meant to suggest that objectors to the official interpretation of the Civil War are in the same company as those “revisionists” who deny Nazi atrocities in World War II.

Honest historians understand that they have their own sympathies, values, and assumptions, and try to allow for their own bias in interpreting the past. Advocates of the present orthodoxy do not qualify as honest historians. The orthodoxy is believable only from the starting point of a number of unacknowledged and unexamined beliefs: The assumptions are so much a part of the mental equipment of contemporary intellectuals that they are not even aware of them. Assumptions:

*That one need pay no attention to any Southern viewpoint because Southern words were always and only rationalizations for evil deeds and motives.

*That one need not examine the motives, agenda, and behaviour of abolitionism because it was the instrument of revolution, resistance to which is always justly exterminated.

*That Southerners had no culture of their own, no distinct identity, no worthy qualities, not even any intelligent grasp of their own economic interests—nothing to sustain a right to independence except devotion to slavery. Deeply underlying these unrecognised assumptions is another—Southerners do not really count as Americans and are a disposable people.

When Calhoun rose in the Senate in 1837 he was not launching a pro-slavery conspiracy—he was taking an open and defensive stance against a new and extreme provocation.

He was not declaring that slavery in the abstract was always and everywhere a good thing—he took pains to make clear that he was talking about the existing American society, about a specific historical situation and not a theory. In the discussion that followed his speech Calhoun “denied having pronounced slavery in the abstract a good. All he had said of it referred to existing circumstances . . . .”

He was not throwing up a roadblock to the progress of emancipation because slavery was not dwindling away before he spoke. The most obvious proof that there was no serious possibility of abolishing slavery is that it was flourishing. It was not as large in American life as it had been in the 18th century, but the slaves had increased vastly in number and spread over an immense territory in company with the white population. At no time was slavery economically moribund, though some times were better than others. The economic stagnation that had marked the older South was being overcome by agricultural reform.

True, there had been some quiet progress in individual emancipation. There were more free black people in the slave States than in the free, and they were more prosperous and had a better place in society than in the North. Both Southern and European visitors to the North testified to the depressed and despised condition of the latter. Another of those many facts about the antebellum South that our fairy tale history never mentions. The great man of the North, Daniel Webster, was to point out in the debates over the Compromise of 1850, that it was not Southern spokesmen but the fanaticism of the abolitionists that destroyed the disposition toward emancipation that had flourished before they appeared.

Calhoun was most certainly not acting out of personal ambition or a desire to rule or ruin the Union. A brilliant and experienced man, he understood the operation of the American political system as well as anyone ever has. Thus he knew perfectly well by this time that no statesman could ever again be elected President. He kept his name in play for the Presidency because it lent greater attention to what he had to say. As he said on another occasion, certain politicians were always attributing political stands to personal motives because they were unable themselves to conceive of any motives that were not personal.

And Calhoun was not launching some great innovation in the Southern attitude toward slavery because most of what he had to say was already a well-developed part of American discourse.

Calhoun’s speech of 1837 could be characterised as an aggressive and innovative repudiation of previous American doctrine only in the light of the fairy tale history that there had been a commitment to emancipation at the Founding. The misrepresentation of this occasion was deliberate and malicious propaganda that reveals much about the nature of anti-slavery.

It is still today vigorously asserted that the Founding Fathers contemplated the elimination of slavery, although somehow they did not quite get around to it. Though many of the founding generation regretted the existence of slavery, it is absurd to say that they contemplated a decree of emancipation. It has been pointed out that the Constitution explicitly recognised the existence of slavery in several ways, but that is not the main point that can be made. The idea of some firm but deferred commitment to end slavery rests upon the completely anachronistic assumption that the framers of the Constitution were omnipotent and omniscient sages who were free to design a New World Order out of their divine wisdom. This is a reflection of the nationalist fantasy history that was developing at the same time and in tandem with abolitionism. The Framers not only never had an intention to interfere with the slavery that existed, they would never have dreamed that they had any power to do so. The Constitution was an agreement among the states to preserve their existing societies.

Slavery was not dwindling away on the eve of the American Revolution. The slave population was growing, mostly naturally in pace with the American population in general. In fact, slave ownership was actually increasing in some of the Northern colonies. The two great Revolutionary heroes of Massachusetts, John Hancock and Samuel Adams, were slave-owners who brought their dependants with them to the Continental councils in Philadelphia.

The Northwest Ordinance of 1785, banning slaves from the land north and west of the Ohio river, is portrayed as a conclusive avowal of antislavery determination among the Founders. It was nothing of the sort. Since in the Continental Congress each state had one vote, it more resembles an agreement among the states to divide territory, like the later Missouri Compromise, than a popular determination to advance emancipation. In 1785 the importation of more slaves from Africa was still open and, as far as anyone knew, would remain so indefinitely. If the geography of slavery were not limited, the country could fill up with more black population, which nobody wanted. The natural increase of the slave population was already abundant. Among other things, additional imports to fill up all the unsettled territory of the Union would decrease the value of slave property in the East. So little binding was the territorial restriction on the future of slavery in the Old Northwest that the Illinois legislature not long after statehood gravely considered a proposal to make slavery legal in its borders.

By the time of the Missouri controversy of 1819 – 1820, the situation had changed greatly. Foreign importations were illegal by general consent. The Jeffersonian leadership unequivocally repudiated the attempted restriction on slavery in Missouri and the territories. The retired statesmen Jefferson and Madison agreed that the restriction on Missouri was unconstitutional, was a cynical political maneuver by Federalists to divide Northern and Southern Republicans and achieve rule, and that the extension of slavery was a phony issue. They said so repeatedly and emphatically in their letters. Jefferson even used the term “so-called” to refer to the extension of slavery issue. Forbidding the so-called “extension” of slavery did not free a single slave and in fact retarded gradual emancipation.

It is true that these gentlemen, though by no means all Southern leaders, had previously expressed a desire to be rid of slavery, if that were possible, and that they continued to do so. But in 1819–1820 they also vigorously denied the right of the Northern majority in Congress to interfere with slavery. The antislavery that had appeared in the Missouri issue they regarded as illegal, unwise, inexpedient, hypocritical, and portentous of disaster. This is what Jefferson meant when he referred at the time to “the fire bell in the night.” The terror that awakened him was not slavery but the dangerous portent of anti-slavery.

At the same time Nathaniel Macon of North Carolina, William Smith of South Carolina, and other members of Congress denied that slavery in the South was “barbaric” and defended it as a paternalistic good. John Taylor made the same case in his Inquiry, which he was provoked to publish by the Missouri question. The most solid Jeffersonians of the North tended to agree.

In 1830, seven years before Calhoun uttered “positive good,” Robert Y. Hayne of South Carolina had this to say during his celebrated debates with Webster:

Sir, when arraigned before the bar of public opinion on this charge of slavery, we can stand up with conscious rectitude, plead not guilty, and put ourselves upon God and our country. If slavery, as it now exists in this country, be an evil, we of the present found it ready made to our hands. Finding our lot cast among a people, whom God had manifestly committed to our care, we did not sit down to speculate on abstract questions of theoretical liberty. We met it as a practical question of obligation and duty. We resolved to make the best of the situation in which Providence had placed us, and to fulfill the high trust which had devolved upon us as the owners of slaves, in the only way in which such a trust could be fulfilled without spreading misery and ruin throughout the land.

When in the 1850s a Northern party formed around opposition to the so-called “extention” of slavery, it laid a thoroughly dishonest claim on the name Republican and the heritage of Jefferson. Exclusion of slavery from the territories was portrayed as the Jeffersonian policy and used as a front by a mercantilist party that represented the extreme opposite of all that Jeffersonian Republicanism had stood for. So remote had the Northern understanding of the American past become that a party which existed to force through every policy that Jefferson despised, claimed him. Southerners still understood the Revolution and the Founding in intimate terms. They knew what their fathers and grandfathers had thought. In the North, American history had already become an abstraction, a matter of words to be cherry-picked for ammunition. This itself is an important story but far too large for this occasion.

The conventional accounts of anti-slavery tend to ignore or justify the extremist, hateful, and obviously counter-productive rhetoric that denounced Southerners as enemies, tyrants, pirates, and kidnappers and the South as an alien abomination which must be purged from America. Even less noticed is the economic critique of the South that was flourishing at the same time in the calculations of the most hard-nosed Northern capitalists, who would eventually join with the abolitionists in the Republican Party. While the abolitionists were raging against the planters for abominable cruelty to their dependants, the capitalists were faulting for being bad businessmen, too good to the workers on the plantation and failing to extract the maximum profit from them.

The belief was strong among them that slave labour was unwilling and therefore inefficient, though this theory was somewhat belied by the fact that the immense production of Southern tobacco in the 18th century and Southern cotton in the 19th century made up the overwhelming bulk of American exports. The capitalists and their spokesmen also believed and frequently said that slave labour was more expensive because it required the lifetime support of the worker. Something which for Southerners was a source of pride was seen by Northerners as a foolish waste of profits.If the workers were free to compete for wages, it was thought, productivity would be up and labour costs down. Often, this notion was accompanied by a belief that if lazy Southern blacks and whites could be got rid of and Southern lands settled by industrious New Englanders or Europeans, the profits of cotton would be all the greater and flowing into the pockets of people who really deserved them.

It seems to be the judgment of respected economic historians that the plantation was indeed a highly productive agricultural enterprise. Also, as Calhoun asserted in his “positive good” speech, that the black bondsmen received a greater lifetime return on their labour than industrial workers of the time in the North and Europe. Even before the end of the war and Reconstruction, opportunists followed the Union armies into the South, grabbed land, and set about to get rich with “free labour.” It usually did not work. The Northern capitalist conception of Southern society was as misguided as the abolitionist. This powerful part of anti-slavery should be kept in mind when we hear Lincoln singing the praises of “free labour.”

A planter might well have maximized return on his capital if he could somehow dispose of his land and slaves and invest like rich Northerners in government bonds and the stock of tariff-protected industries. But how could he possibly do this? And if he did so, what was to become of his people and his inherited way of life?

All of this was in Calhoun’s understanding of his world when he rose to speak. Having tried to explicate what he did not say that day, I will next try to understand what he did intend.

SOURCE: From The Abbeville Institute Scholars’ 2008 Conference, ” “Northern Anti-Slavery Rhetoric.”