The history of the South is yet to be written. He who writes it need not fear for his reward. Such a one must have at once the instinct of the historian and the wisdom of the philosopher. He must possess the talisman that shall discover truth amid all the heaps of falsehood, though they were piled upon it like Pelion on Ossa.” —Thomas Nelson Page

One mission of the Abbeville Institute is to explore the origins of Southern identity in the culture of the Old South. The South, in contrast to what we know as “America,” was, in the words of M.E. Bradford, a thing that was “grown, not made.” The political philosophy long defended by Southern spokesmen rested on an implicit assumption that government should be the servant and not the master of society, society being the “grown” product of Providence and government being the “made” construction of man.

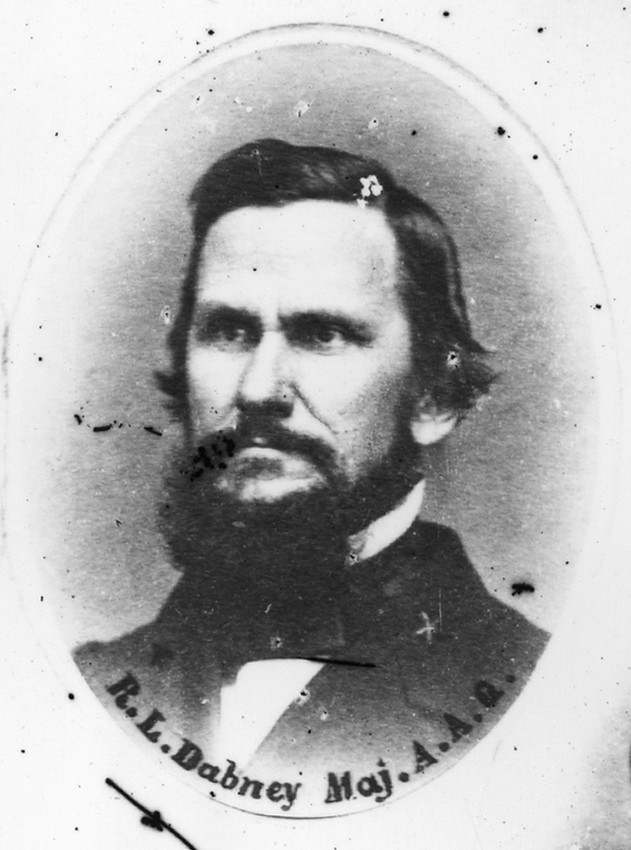

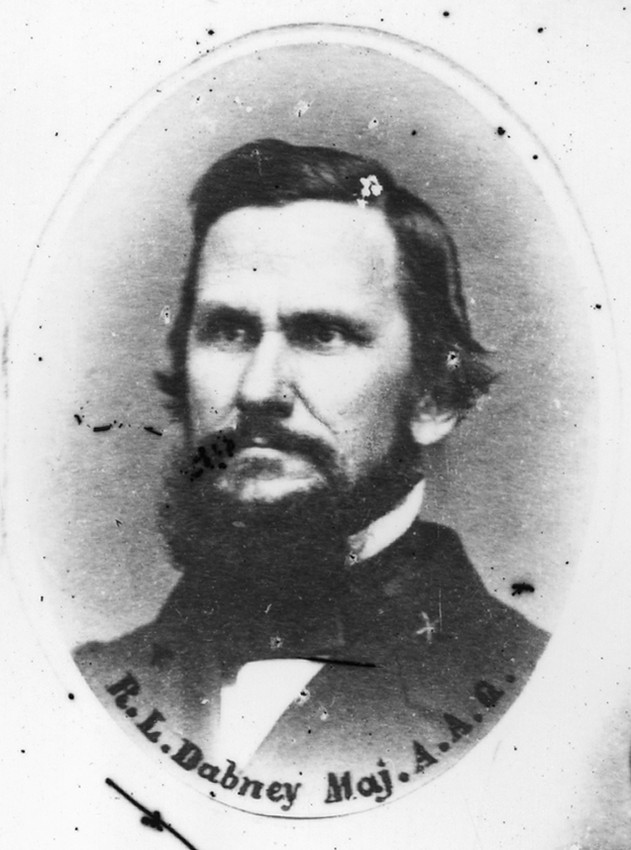

Robert Lewis Dabney, brilliant theologian and late aide to Stonewall Jackson, had occasion to address the students at Davidson College a year after Appomattox. The students were doubtless mostly Confederate veterans and impoverished, making great sacrifice to continue their education—which was typical of Southerners for the next half century. Dabney expresses what Bradford means. He advises the students that they should build and secure the family and thus save the living South even under defeat and evil occupation.

Dabney continues thus:

Government is not the creator but the creature of human society. The Government has no mission from God to make the community. On the contrary the community is determined by Providence, where it is happily determined for us by far other causes than the meddling of governments—by historical causes in the distant past, by vital ideas, propagated by great individual minds—especially by the church and its doctrines. The only communities which have had their characters manufactured for them by governments have had a villianously bad character. Noble races make their governments. Ignoble ones are made by them. [Dabney’s examples of ignoble peoples whose bad character was made for them by governments are Chinese and Yankees.]

In this talk Dabney was summarising what Calhoun had said a few years earlier in his last testament to the world, A DISQUISITION ON GOVERNMENT. And Calhoun was only putting into intellectual form what had been the doctrine of the South from the beginning Society is natural, essential, and self-justifying, proceeding from man’s God-give nature. The legitimate purpose of government is the preservation of society. Thus, the Constitution properly should be the instrument of society’s control of government, not vice-versa. This attitude can be found as far back as Bacon’s Rebellion in Virginia and underlies the political thought and policy of Jefferson. A republican government was defined as a government that rested on the consent of, and preserved the safety of society. It was not created from any theoretical proposition about the Rights of Man, though such a proposition might be one of its justifications. And as Bradford amply showed, the American Revolution was carried out and understood as a preservation of the natural “grown” American society from the threatened dominance of a distant government that had e in its welfare.

The South as a genuine culture, grown not made, has been a continuing obstacle to “America,” which in the course of the 19th century became an abstraction with no cultural reality or tradition, but only the Proposition spelled out by Lincoln—and which requires for its fulfillment that government become the master of society. No genuine Southerner ever set out on a holy mission to stamp out the grapes of wrath.

It is true that the South was not until fairly late in its history—perhaps during Reconstruction— fully conscious of itself as a culture. That does not mean that the South did not exist. In fact, the import is the other way around. It is the South’s very natural reality that made it unself-conscious until attacked from the outside. That the South was not in the beginning fully conscious of itself is used by some to argue that the South does not exist, but is no more than a reactionary defense of racism. According to such a view, there is nothing about the South distinctive or worthy of recognition. “America,” defined as everything except that reaction, is all.

No honest observer can lay the 17th century diaries of William Byrd II of Virginia and Cotton Mather of Massachusetts side by side and fail to note critical cultural differences that were present from the beginning and persist until this day. But to admit that requires admission that there is more than one people and one tradition in this land, which those who claim the exclusive right to define “America” can never admit.

Those who refuse to see the long-continued reality of a Southern identity which is older than the United States only reveal the truth of what they deny. They operate from entirely within the characteristic Northern assumption that America is only noble theory and righteous motives as defined by themselves. That they must impose their theory by force and justify their motives by a claim of righteousness identifies their distinctive culture—a very peculiar thing indeed in world terms.

It might be said that the South did not have to go out of its way to announce and mobilize itself just because it was a real and natural culture and became fully conscious of itself only under outside attack. One European commentator said that The War came because Southerners were a satisfied people and Yankees were restless and demanding. The South was an obstacle to the Proposition (which implied a government instrumental in profit-taking as well as in righteousness) and had to be eliminated. It would never occur to Southerners that it was their duty to correct others—it would be presumptuous and unneighbourly. To them the Union was a friendly agreement, not an instrument to exercise power over others. But to the Proposition Nation, immersed in its own virtue, it seemed and continues to seem natural to recreate others in its own image—or destroy them if they resist too obstinately.

Of course, one may explain everything by simply accepting the unstated and unexamined assumption of almost all current historiography: the South has been perversely and unforgivably evil in resisting “America.” But if one refuses to accept that starting point, then one begins to look for clues for differences between the two parties and for some understanding of what those differences have meant in the unfolding destiny of the American experiment.

Wendell Berry gives us the poet’s view of the Southern tradition of society before government, saying it much better than I ever can:

I sit in the shade of the trees of the land I was born in.

As they are native I am native, and I hold to this place as carefully as they hold to it.

I do not see the national flag flying from the staff of the sycamore,

Or any decree of the government written on the leaves of the walnut….