This essay originally appeared in Defending Dixie: Essays in Southern History and Culture.

In the previous chapter we discussed the early stages of the North American War of Secession of 1861-63 as the minority Lincoln government attempted to suppress the legal secession of the Southern United States by military invasion. In this chapter we will discuss the conclusion of the war and some of its consequences.

In the spring of 1863 General R.E. Lee’s Confederate army crossed the Potomac for the second time in the hope of relieving devastated areas of the Confederacy and bringing the war to a successful conclusion.

For several weeks he maneuvered freely in Pennsylvania without encountering United States forces, which were under strict orders to protect the Lincoln government in Washington. The Confederates observed the rules of civilized warfare, despite the systematic atrocities that had already been visited upon civilians in the South by the Lincoln forces. Pennsylvanians worked peacefully in their fields as the ragged but confident Confederates marched by.

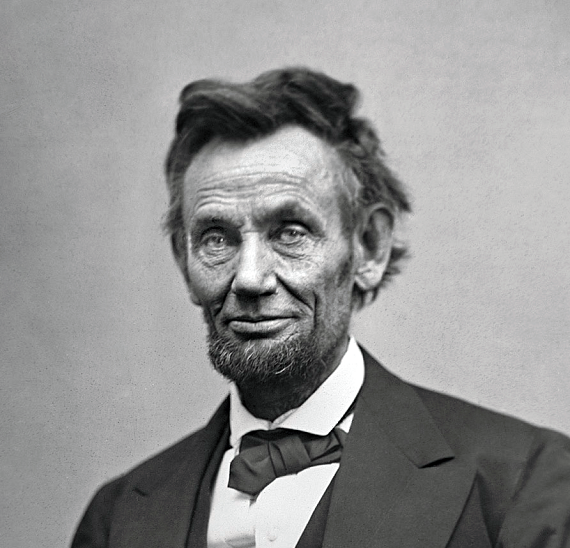

About the first of July, Lee found the US forces entrenched at Gettysburg, a town in Southern Pennsylvania. Though having superior numbers, “Honest Abe’s” armies were unable to initiate any forward movement. (“Honest Abe” was a name given to Lincoln by his early associates and later political enemies, for the same reason that the biggest boy in a class is called “Tiny.”) Union morale was low. While there were many good men in the ranks who had volunteered to fight for the preservation of the American Union, there were also many unwilling conscripts and large numbers of foreigners who had been lured into the army by bounties and who were ignorant of the issues of the war and of American principles of liberty and self-government.

Among the better US soldiers there was much discontent over the recent illegal “Emancipation Proclamation,” which in their view had changed the nature of the war, and over the dismissal of the popular General McClellan. Historians have often noted that, generally speaking, the best generals and soldiers in the “Union” armies were not supporters of the Republican Party or the Lincoln administration. Republicans and especially abolitionists tended to avoid military service in the war they had initiated.

After several days of probing attacks by Lee, the decisive breakthrough came on July 3, the eve of a day revered by lovers of liberty and self-government throughout the world. Pickett’s fresh division and Pettigrew’s seasoned veterans broke through the center of the Union line, its weakest point in terms of terrain. Military historians have noted the striking similarity between this attack and the French breaking of the Austrian center at the Battle of Solferino just four years before.

There were heavy casualties on both sides, but the ever-vigilant General Longstreet exploited the breakthrough and rolled up one wing of the union army. The other wing began retreating toward Washington to defend the government there. The noted Confederate cavalryman Stuart arrived at last and began to dog the retreat, which was made miserable by torrential rains and blistering heat.

Some US troops fought bravely, especially General Hancock, a Pennsylvanian, later President of the US, and Col. Joshua Chamberlain of Maine, later US ambassador to the Confederate States. But when the Democratic governors of New York and Illinois ordered their regiments to suspend fighting and return home, the remaining “Union” forces retreated to the inner defenses of the capital, ironically named for a great Virginian who was a relative of General Lee.

On Independence Day following the battle, former President Franklin Pierce addressed a cheering crowd at the capitol in Concord, New Hampshire. Pierce had never wavered in his support for the Constitution despite threats from the Lincoln government. The tide has turned, Pierce told the audience, and the Constitution and liberty of the Fathers would soon be restored in peace. (It should be pointed out that relatively new telegraph lines made communication almost instantaneous by 1863.)

Lincoln had always been careful to stay away from fighting, visiting his forces only in quiet periods, in contrast to President Davis who was often on the battlefield. Immediately upon receiving the news of Gettysburg, Lincoln wired General Grant, an undistinguished officer who had been trying unsuccessfully for months, with a large force, to capture the small Confederate garrison at Vicksburg on the Mississippi River. Grant was ordered to retreat at once into Tennessee and bring his army by rail to the defense of Washington. For reasons that have long been disputed by historians, Grant refused to carry out his order.

Grant was replaced by General Rosecrans, who attempted to carry out Lincoln’s orders. He found, unfortunately, Confederate General Forrest had got in his rear and destroyed his immense supply bases along the Tennessee River. His hands were further tied by an uprising across central and western Kentucky. Rosecrans finally came to rest near Columbus, Ohio, where he could subsist his army.

Taking advantage of Rosecrans withdrawal, Confederate General Dick Taylor, son of a former President of the US, moved down the Mississippi to liberate New Orleans. The “Union” commanders there, General “Beast” Butler and Admiral Porter, who were unsavory characters even by the standards of the Lincoln party, absconded from New Orleans with $2 million in cotton for their personal profit. They were later heard of in South America, where Butler tried unsuccessfully to make himself President of Uruguay. President Davis was able to declare to the world that now, after two years of obstruction, “the Mississippi flowed unvexed to the sea.”

The rejoicing of the people of New Orleans, white and black, at freedom from military occupation, was riotous. It was truly laissez le bon temps roulez. More importantly, ships began to make their way through the dissolving (and illegal) naval blockage and enter New Orleans and other Southern ports, bringing much needed munitions and medicines. Among the ships were a number from the Northern States looking for cotton and ready to pay gold rather than the rapidly depreciating US greenbacks. A number of Lincoln’s strongest New England supporters were involved in the trade, which was illegal to them by Lincoln’s order.

A small force left behind in Mississippi by Rosecrans was captured by Forrest. The commander of this force was one General Sherman. Among papers found with Sherman were plans from the Lincoln government for a war of terrorism to be waged systematically against women and children in the South. These included detailed instructions, with illustrations for the soldiers. Houses were to be pillaged and then burned, along with all farm buildings and tools and standing crops. Livestock was to be killed or carried away and food confiscated or destroyed.

Particular emphasis was laid on destructions of family heirlooms – pictures of dead loved ones, Bibles, wedding dresses, and pianos. There were also directions as to how to persuade, or coerce if persuasion failed, black servants into divulging the whereabouts of hidden valuables.

The revelation of these papers shocked the world and played a significant part in the later war crimes trail of Lincoln. Sherman had issued additional orders, urging his soldiers to “make the damned traitorous rebel women and children howl.” At his trial later, Sherman defended himself. His actions had been called for, he said, because Americans had too much freedom and needed to be brought under obedience to government like Europeans. The trial of the United States vs. Sherman resulted in a famous precedent-setting verdict of not guilty by reason of insanity.

Meanwhile, Lee waited outside Washington without attacking and the Confederate government renewed the offer made in 1861 and never answered, to negotiate all issues with the US in good faith, on principles of justice and equity. Many of the remaining Union soldiers slipped quietly away, consoling themselves with a popular song in the New York music halls, which went, “I ain’t gonna fight for Ole Abe no more, no more!”

There then occurred one of the extraordinary unexpected historical events, which brought about a dramatic shift in the situation. Lincoln attempted to escape Washington, as he entered, in disguise. He was taken prisoner by Colonel Mosby, a Confederate partisan who operated freely in northern Virginia. Very shortly after, Mosby’s men intercepted a band of assassins intent on killing Lincoln. It was soon revealed that Booth, a double agent, had been hired by the “Union” Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, and certain Radical Republican leaders in Congress, to remove “Honest Abe” and make way for a military dictatorship under a reliable Republican.

Subsequently indicted by the US for his part in the attempted assassination, Stanton hanged himself in his prison cell, shouting, “Now I belong to the ages!” Vice President Hannibal Hamlin fled to Boston and then to Canada where he issued a statement that he bore no responsibility for the illegal acts and aggressions committed by the administration.

Relieved of military pressure, Maryland, Delaware, Kentucky, and Missouri convened conventions of the people in free elections, seceded from the Union, and asked to join the Confederate States. With some opposition they were admitted to the Confederate Union. Meanwhile, California and Oregon declared their independence and formed a new Confederacy of the Pacific. The CSA was the first to recognize this new union.

Needless to say, the successful establishment of independence by the seceding States had far-reaching consequences, not only in North America, but throughout the world. The great American principle that governments rest upon the consent of the governed had been conspicuously vindicated.

With the capture of Lincoln, the flight of Hamlin, and discrediting of the would-be assassins in Congress, the North was without a head. An unprecedented agreement among governors, later vindicated by constitutional amendment, advanced the 1864 elections to the fall of 1863. Vallandigham of Ohio and Seymour of New York, both strong opponents of Lincoln’s usurpations, were elected President and Vice-President, with a Democratic Congress. Outside of New England and industrial centers dominated by pro-tariff forces, the Republican Party fell away in strength, though the pompous Senator from Massachusetts, Charles Sumner, and the fanatical Stevens of Pennsylvania led a bitter minority in Congress.

Immediately upon his inauguration, President Vallandigham accepted the Confederate offer of negotiation. In a moving address to the country he expressed his wish that the real Union, the one established by the Fathers for all Americans, could be reunited. But he feared the scars of war had made this impossible. All could take comfort in the fact that there were now two great free confederacies favoring the world with examples of liberty and self-government.

The Confederate States waived demands for reparations. The resulting treaty of peace and friendship had two main provisions. As to territory, the Confederacy was recognized as ruler of the Indian territories and the southern portion of New Mexico (later Arizona) and Union-seized western Virginia was returned to the Old Dominion.

The other important provision provided for a lasting cancellation of all tariff barriers between the two Unions. This establishment of the principle of free trade over the Continent (it had been preceded by the repeal of the British Corn Laws) must be given credit for the flourishing prosperity of the two confederacies that followed, as well as their immunity from the imperial wars that have wracked Europe and Asia. It is noteworthy that the Republican tariff industrialists, who fought free trade tooth and nail, found that their profits were not lost, as they had feared, but increased.

President Vallandigham and the Democratic Congress of the US returned to Jeffersonian principles not only on the tariff but across the board. The debacle of the Lincoln administration and its corruption had provided all the evidence needed of the abuses and danger of centralized government. War contracting had showed up tremendous graft for political favorites. Expenditures were curtailed, corruption prosecuted (it was said at one point that every other Lincoln appointee was in jail or under indictment), and the national banking fraud dismantled. The corrupt and brutal Indian policy of Lincoln was terminated in favor of a return to the moderate Jeffersonian policy. To this is attributed the subsequent relative freedom of the US from Indian wars.

There remained one vexing problem. What to do with Lincoln, in comfortable confinement in Richmond, receiving every courtesy from his captors. Doubtless the failed President’s disappointment and sorrow were deepened when his son Robert, who had spent the war at Harvard, denounced Lincoln as a fraud and a failure and attempted to launch his own political career, and Mrs. Lincoln had to be confined to a mental asylum. (The indictment of Mrs. Lincoln for unauthorized expenditures from the White House accounts was quietly dropped.)

The fate of Lincoln became the subject of international interest. Count Bismarck of Prussia and the Czar of Russia called an international conference in support of Lincoln, which justified his actions on the grounds that legitimate governments must have the power to suppress rebellious subjects and provinces. Britain, France, and many of the smaller states of Europe countered with a declaration upholding the American doctrine that governments rest on the consent of the governed.

An idea that gained attention at the time was put forward by the Rev. Mr. Joseph Wilson, a Presbyterian minister in Augusta, Georgia. The peace-loving nations should establish a world government to punish aggressions such as those Lincoln had committed. After all, such offences were against all humanity and not just invaded peoples. The press soon reported that the idea had really come from the Rev. Wilson’s twelve-year old son, Woodrow. (Woodrow, who became a college president, was later noted for his fruitless lectures in favor of world government.)

Who did have jurisdiction over the numerous crimes? True, Lincoln had made unscrupulous war upon the Southern people in an attempt to suppress their freedom. But he had also, in so doing, violated the Constitution of the United States and caused great suffering to the citizens of the US. After mature consideration, Lincoln was turned over to the authorities of the US to be prosecuted in their courts. Ironically, the Confederate Vice-President Alexander Stephens, an old friend of Lincoln, volunteered for his defense team.

The list of indictments was long:

- Violation of the Constitution and his oath of office by invading and waging war against states that had legally and democratically withdrawn their consent from his government, inaugurating one of the cruelest wars in recent history.

- Subverting the duly constituted governments of states that had not left the Union, thereby subverting their constitution right to “republican form of government.”

- Raising troops without the approval of Congress and expending funds without appropriation.

- Suspending the writ of habeas corpus and interfering with the press without due process, imprisoning thousands of citizens without charge or trial, and closing courts by military force where no hostilities were occurring.

- Corrupting the currency by manipulations and paper swindles unheard of in previous US history.

- Fraud and corruption by appointees and contractors with his knowledge and connivance.

- Continuing the war by raising ever-larger bodies of troops by conscription and hiring of foreign mercenaries and refusing to negotiate in good faith for an end to hostilities.

- Confiscation of millions of dollars of property by his agents in the South, especially cotton, without legal proceedings.

- Waging war against women and children and civilian property as the matter of policy (rather than as unavoidably incident to combat). (General Sherman and others were called to testify as to their operations and the source of their orders.)

Two questions widely discussed at the time could not be formulated into systematic charges against Lincoln. One was the huge number of deaths among the black population in the South as a result of forcible dislocation by “Union” forces. No accurate account was ever achieved, but the numbers ran into several hundred thousand persons who had died of disease, starvation, and exposure on the roads or in the army camps.

The second unpursued charge had to do with the deliberate starvation and murder of Confederate prisoners. When Lincoln was captured, the guards fled the camps where these prisoners had been confined. Many Northern citizens were willing to testify to the terrible conditions in the camps – exposure and starvation where food and medicine were readily available. One of the strongest impulses for the restoration of good feelings between the former compatriots of the North and South was the Christian aid and comfort given by many Northerners for the relief of these prisoners.

These atrocities could not be directly charged to Lincoln, though they were pursued against a number of lesser officers. Lincoln was charged with contributing to numerous deaths by being the first civilized authority to declare medicine a contraband of war and refusing the Confederate offer to allow Northern doctors to attend the Union prisoners in their hands.

The trial, long and complex, was held in the new US capital, Chicago. Eminent lawyers were engaged on both sides. A number of Radical Republican politicians, hoping to revive political careers, were eager to take the stand against their former president.

The impression that most observers had of Lincoln at the trial was that of a wily corporate lawyer and astute political animal and of a powerful but somewhat warped personality. His employment of specious arguments and false dilemmas, semantic maneuvers, and homely and sometimes bawdy anecdotes to divert attention from the prosecution’s points, became increasingly transparent as the weeks of the trial wore on.

The high point of the trial came when Lincoln, on the stand, avowed that though he now regretted much that had happened, everything had been according to God’s inscrutable will and he had acted only so that government of the people, by the people, and for the people should not perish from the earth. The courtroom erupted in guffaws, whistles, and howls of derision that went on for an hour.

Found guilty, the former leader’s sentence was suspended on condition that he never enter the territory of the United States again. His subsequent wanderings became the subject of a famous story and play, “The Man Without a Country,” and were most notable for his collaboration with Karl Marx, whom he met in the British Museum Library, in the early Communist movement that was to have so great an impact on European history.

About the time the war crimes trial ended, General Lee was inaugurated as the second President of the Confederate States. Speaking by the statue of Washington on the capitol grounds at Richmond, he described the first recommendations he would send to Congress. The Southern people had been deeply moved by the loyalty and shared suffering of most of their black servant population during the war. It was time to fulfill the hopes of the Southern Founders of American liberty. He called for a plan that would provide freedom, at the age of maturity, along with land or training in a skilled trade, for all slaves born after a date to be set. The plan had already been approved by the clergy of all denominations in the Confederate States and by many other leading citizens. (It is to Lee’s farseeing wisdom that peaceful relations between white and black in the CSA have not been disrupted by the strife that has characterized other countries of the New World.)

In closing, Lee advised the people of the free Confederacy to put aside all malice and resentment, look forward to the future, and give thanks to the Almighty for his infinite mercy in vindicating to the world the great American principle that governments rest on the consent of the governed.