“To parties of special interests, all political questions appear exclusively as problems of political tactics.”

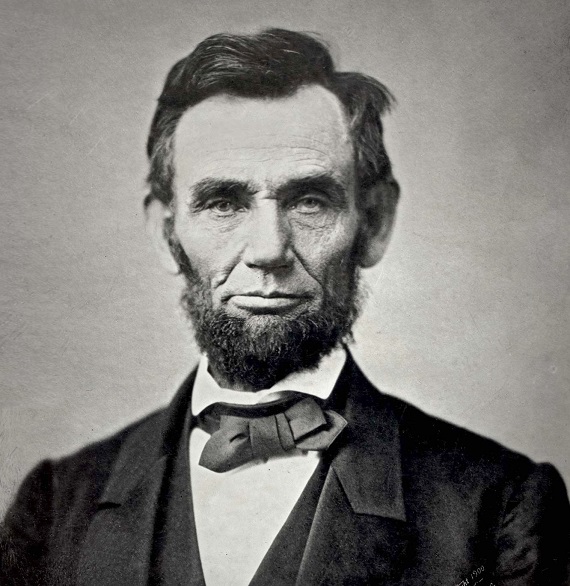

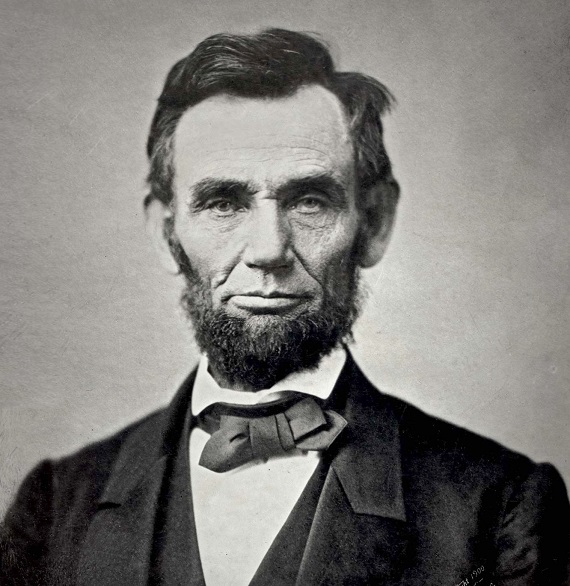

I want to take a look at this strange institution we know as the Republican party and the course of its peculiar history in the American regime. The peculiar history both precedes and continues after Lincoln, although Lincoln is central to the story.

It is fairly easy to construct an ideological account of the Democratic party, what it has stood for and who it has represented, even though there has been at least one revolutionary change during its long history. I generalize broadly, because all major political parties since at least the early 19th century have most of the time sought to dilute their message to broaden their appeal and avoid ideological sharpness. But we can say of the Democratic party that through most of its history it was Jeffersonian—it stood for, at least in lip service, a limited federal government and laissez-faire economy, and it represented farmers and small businessmen, the South, the pioneer West, and to some extent the Northern working class. This identity for the most part even survived the War to Prevent Southern Independence. Clearly, the party in the 20th century came to represent a very different platform—social democracy as defined by the New Deal and the Great Society—and a considerably different constituency. In either case, onlookers have had a pretty good general impression of what the party stood for.

It is nearly impossible to construct a similar description of the Republican party. The party that elected Lincoln was pretty clear about some things, like the tariff, although it may have been less than honest about the reasons. It was obfuscatory about other things. Since Lincoln took power, it has been difficult to find a clear pattern in what the party has claimed to represent. The picture becomes even cloudier when you compare words and behaviour. This, I believe, is because its real agenda has not been such that it could be usefully acknowledged.

Apparently millions continue to harbor the strange delusion that the Republican party is the party of free enterprise, and, at least since the New Deal, the party of conservatism. In fact, the party is and always has been the party of state capitalism. That, along with the powers and perks it provides its leaders, is the whole reason for its creation and continued existence. By state capitalism I mean a regime of highly concentrated private ownership, subsidized and protected by government. The Republican party has never, ever opposed any government interference in the free market or any government expenditure except those that might favour labour unions or threaten Big Business. Consider that for a long time it was the party of high tariffs—when high tariffs benefited Northern big capital and oppressed the South and most of the population. Now it is the party of so-called “free trade”—because that is the policy that benefits Northern big capital, whatever it might cost the rest of us. In succession, Republicans presented opposite policies idealistically as good for America, while carefully avoiding discussion of exactly who it was good for.

There is nothing particularly surprising that there should be a party of state capitalism in the United States. And certainly nothing surprising in the necessity for such a party to present itself as something else. Put in terms the Founding Fathers would have understood, the interests Republicans serve are merely the court party—what Jefferson referred to as the tinsel aristocracy and John Taylor as the paper aristocracy. The American Revolution was a revolt of the country against the court. Jeffersonians understood that every political system divides between the great mass of unorganized folks who mind their own business—that, is, the country party—and the minority who hang around the court to manipulate the government finances and engineer government favours. It is much easier and quicker to get rich by finding a way into the treasury than by risk and hard work. That is mostly what politics is about. Of course, schemes to plunder society through the government must never be seen as such. They must be powdered and perfumed to look like a public good.

Contrary to what we might hope, there was nothing in the New World to inhibit the formation of a court party. In fact, the immense riches of an undeveloped continent merely increased incentives for courtiers. The number of projects that could be imagined as worthy of government support was infinite. In America there were not even any firmly established institutions of credit and currency, control of which was always the quickest route to big riches. Neither was there anything in a democratic system to inhibit state capitalism. The great mass of the citizens could usually be circumvented by people whose fulltime job was lining their pockets by swindling the voters. Lincoln’s triumph is most realistically seen as the permanent victory of the court party, a victory that had been sought ever since Alexander Hamilton. The Lincoln regime eliminated all barriers to making the federal government into a machine to transfer money to those interests the party represented (and as many others as needed to be paid off to support the operation).

Hamilton had justified the government enriching his friends at no risk to themselves because “a public debt is a public blessing.” The Whigs sometimes argued that the paper issued by their banks was “the people’s money” and therefore morally superior as a currency to “government money.” Lincoln presented himself as a candidate for the presidency with the slogan “Vote Yourself a Farm!” Once the obstructionism of those troublesome Southerners was broken, ordinary folks could get themselves a farm for free out of the public lands. Some ordinary folks did get land—but most of the free land, millions of acres, went to government-connected corporations. Saving the Union, freeing the slaves but keeping them out of the North, and giving opportunity to the common people, when filtered through Lincoln’s masterful rhetoric, gave the party of Big Business a lock on the righteous vote for a long time to come..

The most consistent aspect of Republican party has been its role as the respectable party, without much attention to principles and policies. Its voters have been those who think of themselves as more respectable and more patriotic than the voters of the other party. What I am trying to describe is captured by the pejorative label the Republicans long used for their Democratic opponents.The Democrtas were said to be the party of “Rum, Romanism, and Rebellion,” that is, of wastrels, Catholics, and Southerners. The bloody shirt was waved through decades in which the party definitely had an agenda, but one which was not described too frankly. When the current Republican radio demagogues anathematize liberals they are merely appealing to the same vague feelings of superior virtue that fueled “Rum, Romanism, and Rebellion.” The one attitude that Republicans have most consistently displayed is disdain for the South, because such an attitude has been always highly respectable and was the basis of their first rise to power. In their platform of 1900 they justified the slaughter then going on in the Philippines by likening the rebels there to the Southern traitors of earlier times who deserved death for the evil deed of resisting the best government on earth. Very recently, the national chairman of the Republican party went before a civil rights group to apologize for that party’s “Southern strategy.” As far as I know he did not repudiate the seven out of the last ten national elections that were won by that strategy.

The Republican party has had to live with a large gap between what it says and what it does. Deceit has become a habit and a fixed policy. Republican leaders always, and I mean always, act as if truth is the worst possible strategy—always opt for the gimmick instead of straight talk. Richard Nixon—like Lincoln a crackpot realist—thought only of damage control when simple truth-telling might have saved him. It might occur to some observers that the crackpot realist mode describes pretty well the way a recent war was started and carried on. What I am trying to describe here is something more than the usual elasticity of politicians who lie as a tool of the trade. When Charles Beard’s ECONOMIC INTERPRETATION OF THE CONSTITUTION was published, suggesting that theretofore unseen profit-seeking had had a major role in the creation of the U.S. Constitution, Republican President William Howard Taft is said to have commented that what Beard wrote was true but it should not have been told to the public.

The very name of the Republican party is a lie. The name was chosen when the party formed in the 1850s to suggest a likeness to the Jeffersonian Republicans of earlier history. This had a very slender plausibility. One of the main goals of the new party was “free soil”—preventing slavery (and black people) from existence in any territories, that is, future states. It is quite true that in the 1780s Jefferson, and indeed most Southerners, had voted to exclude slavery from the Northwest Territory—what became the Midwest, a region to which Virginia had by far the strongest claim by both charter and conquest. However, the sentiments and reasoning that supported that restriction were very different from those of the Republican Free-Soilers of the 1850s.

To detect the lie, all you have to do is look at the stance of Jefferson himself and most of his followers, Northern and Southern, in the Missouri controversy of 1819–1820. The effort to eliminate slavery from Missouri and all the territories, the first version of Lincoln’s free-soil policy, was denounced by Jefferson as a threat to the future of the Union and a transparent Northern power grab. It was “the fire-bell in the night.” In the 1780s the foreign slave trade was still open. In 1819 no more slaves were being imported and the black population was increasing naturally in North America at a greater rate than anywhere else in the world (as it always has). At that point, Jefferson said, the best course for the eventual elimination of slavery was not to restrict it but to disperse it as thinly as possible.

The Southern Republicans who had criticized and sought to restrict slavery in the 1780s had in mind the long-term welfare of all Americans. The Northern Republicans of the 1850s who raised a truly hysterical and exaggerated campaign against what they called “the spread of slavery” were entirely different people with entirely different motives. Not even to mention, of course, that the Northern Republicans were totally committed to a mercantilist agenda, every plank of which Jeffersonians had defined themselves by being against. The Republicans of the 1850s exactly represented those parts of the country and those interests that had been the most rabid opponents of Jefferson and his Republicans. (Interestingly, the areas of the country today that are the most liberal—the northeast, upper midwest, and west coast, are exactly the areas that from the 1850s to the 1930s were the most solidly Republican–and “respectable.” (Old fashioned Democrats used to say that the change from a small government party to a leftist one was a take-over of the Democrats by Republican Progressives.)

In 1860 the Republicans promoted their candidate as the “rail-splitter,” the poor boy who had made good, an example and representative of the “common people.” This image, of course, had nothing to do with the Lincoln of 1860, with his agenda, or with the important issues of the time. This was not new. It was a mimicry of the Whig campaign of 1840. For a long time our New England-dominated history books have portrayed the election of the natural aristocrat Andrew Jackson in 1828 as beginning a vulgarization of American politics. But it was actually the Whig campaign of 1840 that successfully pioneered the transformation of national political campaigns into mindless mass celebrations. It showed how it is done. The party did not trouble itself to adopt a platform nor to nominate for President any of its well-known leaders. It put up the elderly General Harrison of Ohio, who had been a hero in the War of 1812 and a senator and governor some time back. General Harrison entertained company but issued no position papers. His candidacy was promoted by a slogan “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too” and by mass torchlight parades and rallies featuring the log cabin in which Harrison supposedly lived, the coonskin cap he supposedly wore, and the jug of home-distilled from which he supposedly sipped. The general actually lived on quite a considerable estate near Cincinnati and was a Virginia aristocrat by birth. In fact, he and his running mate, John Tyler, had both been born in the same small county in Tidewater Virginia.

As a further obfuscation, Tyler had been added to the ticket to appeal to Southerners who were opposing the controlling Van Buren Democrats for quite different reasons than were the Whigs. Harrison swept the Middle States and Midwest, though his victory probably owed as much to a bad economy and Van Buren’s lack of appeal as to the Whig campaign. Immediately Henry Clay, hero and Congressional leader of the Whigs, announced that the election was a mandate for the Whig program—raising the tariff up again, re-establishing the national bank, and distributing lavishly from the treasury to companies that promised to build infrastructure. All this, although the issues had never been set forth in a platform nor mentioned in the campaign. Remind you of any more recent Presidential mandates for things that were never discussed before the voters?

The “log cabin” gambit has been used and re-used as when the Wall Street lawyer Wendell Wilkie was promoted as a simple Hoosier country lad, and two rich Connecticut candidates were marketed as “good ole boys” from Texas.

Let’s look at Lincoln’s party as it was born in the 1850s. In March of 1850, William H. Seward, the chief architect of the Republican party and its foremost spokesman until Lincoln maneuvered him out of the Presidential nomination, made a speech against compromise, anticipating his later famous remarks about “the irrepressible conflict” between North and South. This speech was not a somber warning about impending trouble as is usually assumed. It was a celebration of the coming certain triumph of the North over the South. James K. Paulding, New York man of letters and former Secretary of the Navy, wrote about Seward’s oration:

I cannot express the contempt and disgust with which I have read the speech of our Senator Seward, though it is just what I expected from him. He is one of the most dangerous insects that ever crawled about in the political atmosphere, for he is held in such utter contempt by all honest men that no notice is taken of him till his sting is felt. He is only qualified to play the most descpicable parts in the political drama, and the only possible way he can acquire distinction is by becoming the tool of greater scoundrels than himself. Some years ago, after disgracing the State of New York as Chief Magistrate, he found his level in the lowest depths of insignificance and oblivion, and was dropped by his own party. But the mud was stirred at the very bottom of the pool, and he who went down a mutilated tadpole has come up a full-grown bull frog, more noisy and impudent than ever. This is very often the case among us here, where nothing is more common than to see a swindling rogue, after his crimes have been a little rusted by time, suddenly become an object of public favour or executive patronage. The position taken and the principles asserted by this pettifogging rogue in his speech would disgrace any man—but himself.

Paulding adds: “I fear it will not be long before we of the North become the tools of the descendants of the old Puritans . . . .” He means that the well-known and much despised New England fanaticism was encroaching upon the whole North.

This is one Northern commentary on the origins of the Republican party and on the sad public conditions that made it possible. Failed politicians of both parties, like Lincoln, had seized the occasion of the acquisition of new territory from Mexico to launch themselves forward in a way destructive of the comity of the Union. The opportunity they made the most of had two parts: the discontent of major Northern economic interests over free trade and separation of the government from control of the bankers that had been accomplished by the Democrats; and the hysterical and false claims that Southerners were conspiring to spread slavery to the North, given plausibility by three decades of vicious vituperation against the South. The Republican success depended on a Northern public that was unsettled by economic change, religious ferment, and immigration. Thus these politicians were able to form for the first time in American history a purely sectional party, something that every patriot had warned against.

Almost all current interpretations of the meaning of the Republican war against the South 1861-1865 come to rest on pretty phrases from Lincoln’s speeches. If you look at primary sources, as historians used to do, you get a very different picture. In their private letters and sometimes in public speeches the Republican leaders reveal themselves to be just the ruthless villains that several previous generations of historians knew them to be. They boast about their intention to keep control of the government by any means, to keep the South captive for economic exploitation, sometimes about their intent to exterminate the Southern people. (Those in favour of the last-mentioned are usually New England clergymen.) They revel triumphantly in conquest in a manner that puts one in mind of Nazis. As for the glory of emancipation that so long lent righteousness to their war, as Frederick Douglas pointed out, Lincoln’s party was pre-eminently the party of white men. Before, during, and after the war the Republicans never did anything with a primary motive of the welfare of the black people. The black people were for use for higher purposes, for keeping down the South and keeping the Republicans in power. Most importantly, they were to stay in the South. Millions of acres of vacant western land could be given away to corporations which could provide the representatives of the people with the proper cash incentives, and to white immigrants, but there was not a patch for the freedmen.

In the free-soil debates before the war Republican leaders dwell not on the evil of slavery but on their intention to keep the black scourge out of the new territories, which must be reserved for white men only. Senator Benjamin Wade of Ohio, stalwart Radical Republican, writes his wife that he hates to go to Washington because of all the n-words there. If you look at the iconography of Emancipation, what you see is not a celebration of black freedom but a celebration of Northern nobility of which the blacks are the passive and slavishly grateful beneficiaries.

What other elements besides opportunistic politicians went into making this new party? Obviously the powers of industry and finance that would know how to profit from a new regime. And the New England intelligentsia for whom, by common consent, we can cite Ralph Waldo Emerson as the representative. Emerson who said he was more concerned about one white men corrupted by slavery than about a thousand enslaved blacks; who also said that the inhabitants of the Massachusetts penitentiary were superior to the leaders of the South; and that serial killer John Brown was a great man.

Another major ingredient in the Republican confection were the nativists formerly of the American party. Lincoln was too shrewd to come right out as a nativist, but he gladly accepted the support of the people who had torched convents in Boston and Philadelphia. It is not very well known that nativist vigilantes called “Wide-Awakes” carried out mob action against enemies of the Republican party before and during the war. And you thought only Southerners were guilty of mob violence.

Another founding block of the Republican party, often overlooked, were German refugees from the 1848 revolutions. Their numbers in the Midwest, as much as fifteen per cent of the population in some states, were great enough to form a major voting block and to account for the change of the Midwest from Democrat to Republican between 1850 and 1860. In other words, there were just as many state rights Democrats in the Midwest in 1860 as there had been in 1850, but they could now be outvoted. Lincoln cultivated this cohort early by secretly subsidizing its newspapers and involving its leaders as activists in his behalf. For the new Germans the predominant nativist Puritans of the North made an exception to their dislike of all non Anglo-Saxons. In the German revolutionaries they found spiritual kinsmen.

Pre-1848 German immigrants, German Catholics, and those belonging to quieter Protestant sects did not participate in Republican fervor. Let’s understand who these German Republicans were. They were military nationalists. You can call them proto-communist or proto-fascist, it doesn’t matter. It amounts to the same thing. When the foremost among them, Carl Schurz, arrived in America he complained that the Americans were too laid-back and unideological in their politics and he vowed to change that. These Germans believed that the unified and aggressive nation-state was the height of human existence, that progress toward it was inevitable, and that obstacles to centralization and revolution should be violently destroyed like the provincial aristocracies and petty princes of Europe. These Germans were among the most active and aggressive of Republican orators and campaigners and motivated Union soldiers. Before they arrived, America had been marked by a regional conflict between Northerners and Southerners with contradictory interests and inclinations. With the rise to influence of the Forty-Eighters the manageable competition of different regions became in the Northern mind an ideological class conflict. On one side was Freedom and the nation. On the other side an evil force called the Slave Power, a deadly enemy that must be destroyed like any other obstacle to the fulfillment of national glory.

So that, as he records in his memoirs, General Richard Taylor of the Confederate Army, son of a President of the United States and grandson of a Revolutionary officer, when he surrendered in 1865, was lectured by a German in a federal general’s uniform about how Southerners were now going to be forced to learn the true principles of America. (I always think of the “scholarship” of Harry Jaffa when I recall this incident.)

Let us always come back to the fundamentals. The Republican party engineered and carried out a bloody war against Americans that revolutionized the basis on which our liberty had been built. They maintained a cold war for another decade, governing by force and fraud, unprecedented in American history. While in power they bribed, swindled and looted themselves to private wealth that still underpins many fortunes. Historians of the first half of the twentieth century, whether liberals or conservatives, read the sources and understood this. They regarded what had occurred as a great national tragedy. But now it is all rendered in Marxist terms (whether those who are following the line realize it or not) as a great revolution that unfortunately failed to go far enough. Historians now see nothing in the experience but the race question. They condemn the evil Southerners who sometimes intimidated black voters in attempting to bring about an end to the disorder and blatant “legal” stealing of Reconstruction. That during Republican rule there had been pervasive fraud and terror and never an honest election in the occupied territories is not worth mentioning.

I doubt if even Lincoln and his stoutest supporters would agree that their pursuit of power and profit amounted to an unfortunately incomplete Marxist revolution. That was not exactly what they had in mind.

One Comment