If we want to understand the origins and nature of Southern culture we must consider it from the standpoint of the West. Because the South was the West of Britain, created by her sons–though younger sons and only partial heirs perhaps. The South was Britain planted in a New World of vastly different conditions from those left at home.

“The West” in American thought is a somewhat amorphous and elastic conception. We think today of the West as the plains and mountains beyond the Mississippi. But the West was really a process that took place over two and a half centuries. This is the point of Frederick Jackson Turner’s famous observation that American history had been determined by the long existence of a frontier America was the frontier of Europe and the frontier of America once began in the 17th century outside the palisades of Jamestown in Tidewater Virginia.

So Southern history and identity is formed by the settlement of a Continental wilderness. In fact, the South was by far the most dynamic element in the American westward movement and the West over its greatest extent was a Southern frontier.

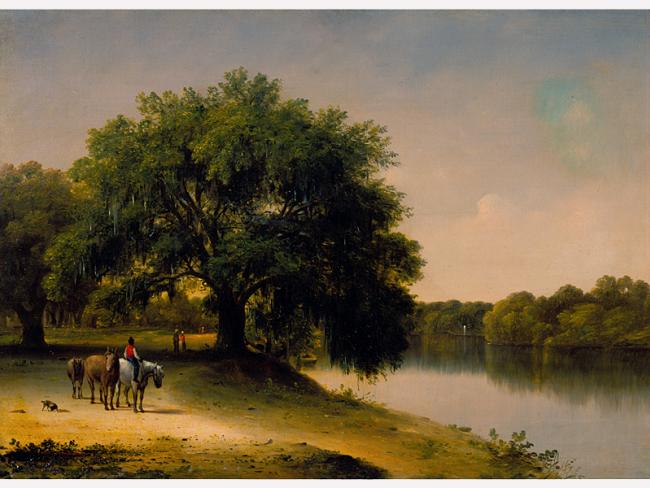

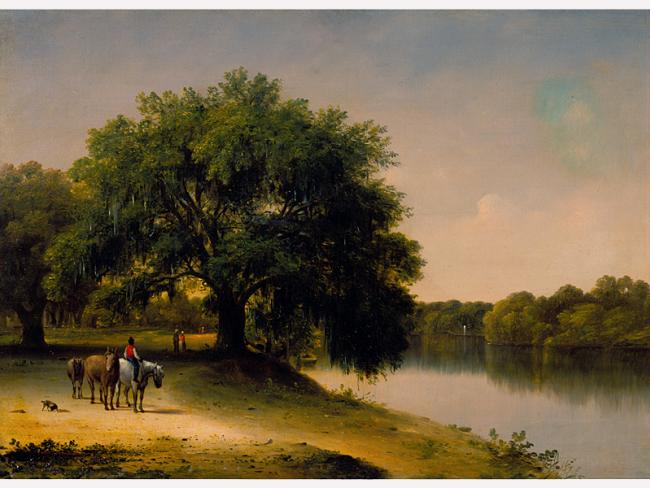

Recreating the society over and over again in new conditions. The history of the South (and thus the most important part of American history) is the history of the mutual adjustment of the plantation and the frontier. One might call this the main theme of Simms and of many later Southern writers. A frontier constitutes a peril for an existing culture—which tends to diminish on the fringe as it seems inapplicable to the imperious demands of new country. The creation of Southern civilization out of this conditions was an immensely successful cultural achievement.

Note simply that in 1860, half the people then living, black and white, who had been born in Virginia and the Carolinas were living somewhere further west.

Students of American history and literature ought to pay a bit of attention to the group of writers called “Southwestern humourists” who flourished in the three decades prior to the War to Suppress Southern Independence. This is, in my opinion, an important subject in the history of American literature and of the South and the West.

This type of writing in book form begins with Augustus Baldwin Longstreet’s Georgia Scenes in 1835, a series of sketches about earlier times when much of the state was newly settled and rude frontier conditions obtained. The titles of some of the stories in Georgia Scenes will help give the flavour of this form of literature: “The Horse Swap,” “The Fight,” “The Shooting Match,” “The Militia Drill.” Like all the writers in this genre Longstreet’s subject was the frontier in the process of forming into a settled civilisation.

In other words it is about the South moving West. There were many writers in this vein, among the more notable: Johnson Jones Hooper who created “Simon Suggs” of Alabama and George Washington Harris who created “Sut Lovingood” of Tennessee. There are many others: Charles Henry Smith’s “Bill Arp,” William Tappan Thompson’s “Major Jones,” Henry Clay Lewis’s “Louisiana Swamp Doctor.” Interestingly, the book most often cited as an example by “scholars” is The Flush Times of Alabama and Mississippi by Joseph Glover Baldwin which is the weakest, least interesting, and least representative of these works.

If you want to pursue this subject, I suggest the best place to start is get John Sanders’s edition of The Adventures of Captain Simon Suggs with my introduction. Suggs leaves the family farm in Georgia after acquiring some capital by beating his awful father at cards. He heads off to Tallapoosa County, Alabama, where he prospers, becomes a prominent citizen, and has a series of adventures, one of which is a raid on a camp meeting which Mark Twain stole for Huckleberry Finn. Suggs’s rule is “It is good to be shifty in a new country,” making him an American archetype.

These writers were never a self-conscious school of literary professionals. They were all busy men who wrote sketches for the newspapers for the amusement of their neighbours and to make some record of what things were like in the early days of their society. Longstreet was a Methodist minister and college president, Hooper a lawyer, Harris a Tennessee River steamboat captain, Smith a farmer. Literature was a gentlemanly pastime and they had no interest in literary self-promotion. But the stories were so popular that they got into national magazines and were collected into books which sold well in the U.S. and Britain.

The beginning of all wisdom in appreciating American literature is to know that the conventional understanding of merit has been shaped by selfish literary politics centered in Boston in the 19th century and New York in the 20th. Throughout the time when the Southwestern writers flourished, New Englanders were engaged in a deliberate and nasty campaign to promote themselves as the only important American writers. (They did the same with the history of the Revolutionary war, ignoring or slandering everybody’s history except New England’s.) Everything that did not have the Boston imprint, if noticed at all, was subpar and unimportant. I shudder to think how many generations of students were turned off of reading for life by exposure to Whittier, Longfellow, Lowell, Thoreau, Bryant, Emerson, etc. as THE best of American literature.

Poe, who was the greatest creative genius among American writers in the 19th century and was an unabashed Southerner, was ignored and insulted. I recommend Poe’s essay called “Boston and the Bostonians” in which he hilariously skewers the literary and intellectual pretensions of those people. He describes Boston as a frog pond in which the bigger frogs thought the pond was the whole world. Poe was not given due recognition and study until well into the 20th century and then mainly because of the interest of European scholars. The record has still not been corrected in regard to William Gilmore Simms of South Carolina, superior to most of the Northern writers as both novelist and poet, who is not included in any of the establishment anthologies of American literature. Simms also wrote at times in the vein of “Southwestern humour”which tells us that the Southern is as important as the Western. His “Sharp Snaffles” stories and his short novel “Paddy McGann: the South Carolina River Boatman” are right in the category of so-called “Southwestern humour.”

Something similar to Poe’s reputation happened with Faulkner. When he received the Nobel Prize, Random House had allowed all of his books to go out of print although translations were still in print in every modern European language. I recommend some of the scathing essays of the lamented George Garrett on the New York literary scene. Tom Wolfe has written an hilarious article called “My Three Stooges” in which he chronicles the efforts of Norman Mailer, John Irving, and John Updyke to destroy his literary reputation while promoting their own. You have to understand this Northeast imperialism to see why the Southwestern humour writers were so long neglected and are still misinterpreted. Incidentally, one of the Southwest humourists, George Washington Harris, is one of the few American writers that Faulkner cited as a positive influence.

In the 1930s, scholars had been emancipated from the Boston-centered view sufficiently to pay attention to Mark Twain. In Twain they found something strong and original and more in tune with the real American spirit than were Boston gentility and guruship.

The next step was to ask where Twain came from. Since it was axiomatic with “scholars” that the South had never produced anything worthwhile, this was a bold step.

Sam Clemens had grown up in Hannibal, Missouri, on the Mississippi river and had traveled up and down that river. He deserted the Confederate army in the first weeks of the war and headed out for Nevada and later California where he began to write stories like “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County.”

The fact is, Sam Clemens had been reading stories like that in local newspapers all his life. That was what was later called Southwestern humour. Part of Twain’s rise to fame was that he was the only such writer who went North and his attitude toward the people he wrote about was basically hateful and disdainful.

The scholars, having noticed Twain’s antecedents, came up with a theory about this literary school. The writers were aristocratic Whigs from the Old South who were ridiculing crude Jacksonian Democrats in the West. This is bunk, applying artifical and misunderstood labels to something living. The writers were mostly from the older South, but they did not treat the frontier as despicable in the way a Northern intellectual would. They were a part of what they wrote about. Simon Suggs is not white trash or a Snopes. He is a substantial middle-class Southern yeoman confronted with challenging frontier conditions.

A major publishing source for “southwestern humour” was a hunting, fishing, and horse-racing magazine called The Spirit of the Times. It was published in New York City and was read by the rural gentry all over America—except, of course, New England. Barely a year before the War broke out, the generous Northern editor, Thomas Bangs Thorpe, wrote this about the school of writing that has been called “Southwestern humour”:

“Some of the best things, always the most original produced in this country, are the results of Southern pens. For more than a quarter of a century the columns of the ‘Spirit’ have teemed with the finest specimens of writing, overflowing with wit and sentiment, playful and profound, a large part of which is destined to become permanent specimens of real American originality, for which we have been largely indebted to Southern correspondents.”

What our writers shared was high spirits, humour, vivid imagination, tough realism, and skillful portrayal of real American life outside the cities and below the genteel. They were profound observers of society and told the great American story—the meeting of civilisation and the frontier. I put forth the claim that here is the true beginning of an original American literature. The writers disdained as mere subliterary “southwestern humourists” are among the most original and creative pioneers of American literature. Almost everybody admits that the South in the 20th century produced an extraordinary number of great writers. These did not come out of thin air. The so-called Southwestern humourists were their ancestors. The later giants took their buckets to the very same well of life and culture as the pioneers had.