According to Deist belief, God does not get involved in the affairs of mankind. He built the celestial clock, wound up the spring and then walked away. There is no point in praying, since the Almighty is not listening. He apparently has other fish to fry. We are left to our own devices.

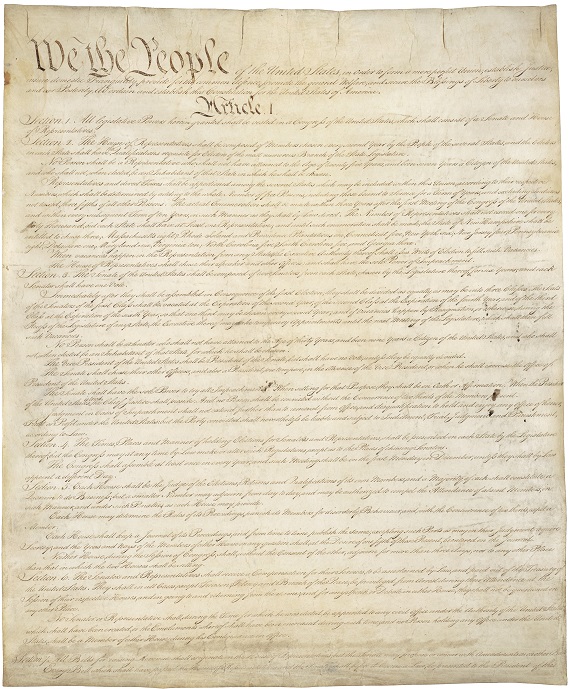

Some look at the system of government of the United States in a similar light. The Founders designed the system, wound up the civil spring and set it in motion, then walked away. No need to refer to their writings and speeches of the time, no need to inquiry what they though they were doing. We are left to our own devices to interpret it as we see fit.

The problem with this is obvious. First, it is an established principle of English Common Law that “The duty of courts of law is undoubtedly to ascertain the intention of the Legislature, and to give effect to that intention, if the language will admit of their doing so, adding nothing to the language and taking away nothing.” Thus, the intentions of the law-givers are not some gnostic knowledge that is at once unknowable and irrelevant. It guides (or should guide) the decisions of courts in ruling on cases.

The Constitution of the United States has two salient characteristics. First, it is amendable. Whenever the people can get two-thirds of both members of Congress and three-fourths of the states to amend, then the amendment becomes law. The amendment process has been successfully resorted to twenty-seven times. The second characteristic is that, as it now stands, the Constitution has the stamp of approval of the people of the United States. Having considered a limitless variety of Federal powers to include amongst those delegated, it has decided to delegate certain powers, and declined to delegate every power not mentioned.

The recent overthrow of the Virginia Constitution’s definition of marriage brought this question into sharp relief. A Federal judge in Norfolk displayed her scant knowledge and concern for foundational documents. Confusing the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, she argued that “Our Constitution declares that ‘all men’ are created equal.” Unfortunately, her reading of the Constitution of the United States was no more accurate. She ruled that the Constitution of Virginia violates the Equal Protection and Privileges and Immunities provisions of the Federal XIV Amendment.

Two approaches to interpreting the Constitution present themselves. One is what Michael Oakeshott called the nomocratic approach, which holds that, in effect, a constitution is a set of rules governing how the government operates. A nomocratic regimes does not presuppose some societal goal to be reached. It does not see an object or end toward which to orient government policy. It does not judge a particular governmental policy as being good or bad depending on whether it advances progress toward that goal or not. Nomocracy judges the goodness of a policy in light of whether it complies with the nomoi, the rules for the government.

On the other hand is the teleocratic approach. Government is a means to some end, some telos. Particular policies are to be judged as good or bad, helpful or harmful, in so far as they further society’s move toward the telos. How society gets to the telos is not as important as progress toward the goal.

Reactions to the Bostic decision have largely depended on whether one holds a nomocratic or teleocratic view of the Federal system of government. A nomocrat looks at Bostic and sees serious flaws with a Federal judge throwing out a portion of a State’s Constitution.

First, the power to define marriage is nowhere delegated to the Federal government. Judge Wright found that the Equal Protection and Due Process clauses of the XIV Amendment give the Federal government the power to overturn a state law or a state constitution where is conflicts with the Federal Constitution. Of course, no Congressman or State Representative in 1866-8 believed that what he was doing was removing from a State the power to define marriage as a union between one man and one woman.

Second, even if the people of a state had intended to surrender the power to define marriage, the people of Virginia obviously negated that delegation in 2007. The legal principle “Leges posteriores priores contrarias abrogant.” Subsequent laws negate contrary prior ones, because the same power that delegates can amend or rescind.

The application of this principle is problematic. The people of a state could not enact a provision that unambiguously negated some provision of the US Constitution without some constitutional questions. For example, if the people of Virginia had declared Virginia to be a hereditary kingdom, then this would violate Article I, Section 9 of the Constitution, as ratified by the people of Virginia in 1788. Either this vote or Virginia’s continued membership in the union of states would have to give. The court’s view that the XIV Amendment denies Virginia the power to define marriage is based on shaky ground, however. It seems more likely (and more in line with republican theory) that the people of Virginia in 2007 were clarifying that their ratification of the XIVth Amendment was not intended to deny Virginia’s power to define marriage, because if the ratification of the XIV had delegated such a power to the Federal government, they would not have adopted the definition of marriage.

A colleague of mine, in discussing this, endorsed the court’s decision to throw out the offending provision of the Virginia Constitution. He is an advocate of same-sex marriage. In discussing this with him, I became convinced that any means to that end was acceptable to him. When I brought up the argument that no one in 1866-8 had intended to delegate to the Federal government the power to deny a state’s authority to define marriage, his response was illustrative. He said, “You are trying to arbitrarily limit the government!” I plead guilty. I pushed him, asking if the decision was acceptable simply because a duly appointed judge had announced the decision, he demurred. I asked if any decision issued by a judge who had been nominated by the President and approved by the Senate (structural legitimacy) or whether he would accept the same policy promulgated simply through a presidential decree (teleocratic legitimacy), he dismissed the question as ridiculous.

One suspects that teleocratic legitimacy best explained his view. Any decision or policy pronouncement that protected same-sex marriage would be acceptable. The fact that it had a plausible veneer of structural legitimacy as well was icing on the cake. It was the end sought, the telos, that mattered. How one got there was irrelevant.

The problem with teloi , however, is their indefinite nature. My colleague, no doubt believes that society has been marching inexorably towards greater freedom and acceptance of homosexuality. Today’s telos, however, is not the telos of yesterday or may not be that of tomorrow. Saint Augustine had a telos in mind, which was very different from the telos Hitler saw as dawning in his Third Reich. At the same time, Stalin had a telos that was altogether different from both of these other gentlemen. These teloi, in turn, are quite different from the multi-culti sexually liberated telos that so many believe that the Zeitgeist is inexorably seeking today.

Therein lies the problem. The telos so inexorably sought after today, even to the extent of running roughshod over the “chains” that “bind men down with the Constitution” may not be the telos five decades hence. The damage to our nomocratic nature of our regime, however, may be permanent. What if in fifty years from now a Muslim majority in the United States and the “telos inexorably sought after” involves not celebrating all sexual orientations equally but eliminating (what the future Muslim majority will see as) the blasphemous homosexual variety? Today’s same-sexuality teleocrats might become tomorrow’s born-again nomocrats, and declare that the Constitution prohibits the Federal government from outlawing homosexuality. The damage, however, will have been done. The Muslim teleocrats of that day will say that the nomos is irrelevant. It is only the telos that matters.

So, let us slow down a bit, and keep our nomos intact and work the system as handed down to us. If the people wish to define marriage in their state constitution, then Federal judges should respect that. Advocates of same-sex marriage should agitate, argue, cajole and seek a re-vote, not run off to the least democratic branch of government seeking to overthrow the principles of self-government. Nomocracy holds to the broad perspective and takes a view of the long term. Let us not abandon it in pursuit of a temporary and malleable telos.