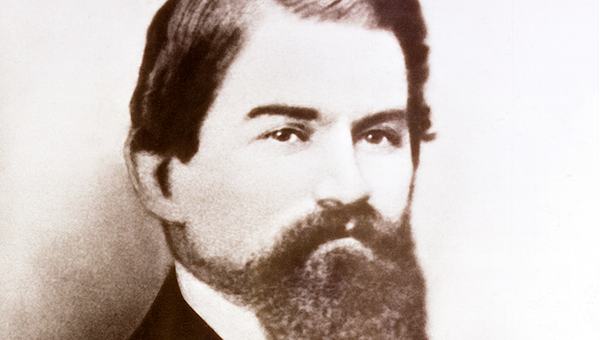

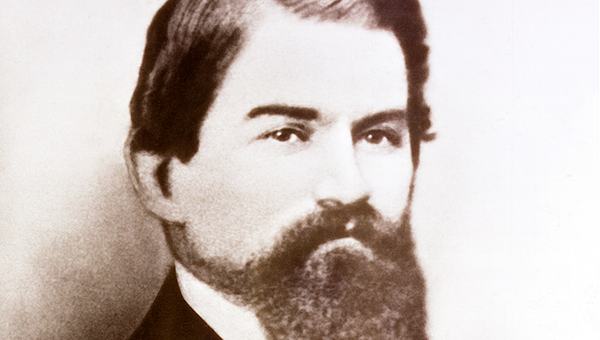

Today (July 8) is Lt. Col. John Stith Pemberton’s birthday. While not as important to the Confederacy as John C. Pemberton, John Stith Pemberton contributed more to American culture and to the image of the New South than virtually any man who donned the gray during the War for Southern Independence.

Pemberton studied medicine at the Reform Medical College of Georgia in Macon and was graduated in 1850 at the age of 19. Five years later he established a pharmacy in Columbus, Georgia, then a bustling industrial town at the fall-line on the Chattahoochee River. By 1860, his lab on Broad Street contained over $35,000 in equipment and he marketed his business as a company dedicated to “manufacturing all the pharmaceutical and chemical preparations used in the arts and sciences.” This included perfume. The ladies of Columbus loved to buy his aromatic concoctions.

Then the War came. Pemberton did not march out with the Columbus Guards in 1861. Only a handful of those men came home. He spent the War like many residents in Columbus, contributing to the War effort through industry. Columbus was the second most important industrial city in the South and manufactured everything from uniforms, rain cloth, boots, and buttons, to munitions, bagging, barrels, and iron, including the unfinished Confederate ram the C.S.S. Jackson.

This was not lost on the Union army. Columbus was targeted by the Yankees in the final months of the War as part of their total war strategy. General James Harrison Wilson hammered through Alabama in 1865, leaving behind a swath of destruction that rivaled that of Sherman’s march to and from the sea in Georgia and South Carolina.

On April 16, 1865 (Easter Sunday), the Union Army appeared on the Alabama side of the Chattahoochee. All able bodied men (and boys) in Alabama (modern day Phenix City) and Columbus readied to defend the city. Pemberton was a lieutenant colonel in the Third Georgia Cavalry Battalion (Home Guard) and bravely faced the occupying army the night of the battle. He was slashed across the chest in the action and almost died from his wounds. Columbus was burned the next day, and like Columbia, South Carolina, after the city surrendered.

Pemberton spent the next year recovering from his wounds, and in the process he became addicted to opium. He put his pharmacy to work looking to find a way to ease his pain without the drug. By 1866, he had produced a product he later called Pemberton’s French Wine Coca, an alcoholic drink that probably contained a trace of cocaine.

When Pemberton moved to Atlanta in 1870, he brought his medicinal recipe with him and marketed it as a cure for several ailments, but in particular as a cure for opium addition. Again, upper class women became his primary customers. Laudanum was a commonly prescribed drug in the nineteenth century for headaches and was highly addictive. Pemberton’s French Wine Coca promised relief without the painful withdraw symptoms of opiates. Pemberton’s career had taken off. He became a trustee of the Atlanta Medical College, later Emory University School of Medicine, and had a business in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania that manufactured and marketed his pharmaceuticals.

When Atlanta went dry in the 1880s, Pemberton was forced to find an alternative to his alcoholic product. While mixing a batch one day he stumbled upon what later became known as Coca-Cola, a mix of the coca syrup (absent the cocaine) and carbonated water. Coca-cola the soft drink was born, but the formula had not changed much since Pemberton first mixed it in Columbus in 1866 as a suffering Confederate veteran.

Pemberton believed that his new non-alcoholic drink–what he marketed as the “ideal temperance drink”–would eventually become a “national drink,” and so in 1887 he incorporated the Coca-Cola Company and let his only son Charles, also an opium addict, run the company. Pemberton died less than a year later of stomach cancer, broke and still helplessly addicted to opium. Just before he died, however, his son persuaded him to sell the company to Asa Chandler for $550. Chandler later made millions on the drink, as did Ernest Woodruff, a businessman from Pemberton’s final resting place, Columbus, GA. Pemberton’s son also later died from complications related to opium addiction without a dime to show from his father’s formula.

Yet, without the War and the Battle of Columbus in 1865, the world may never have been introduced to Coca-Cola, or by default RC Cola and Ne-hi, both invented by Columbus grocer Claud Hatcher after he refused to pay high prices for Coke syrup. Perhaps more than any other drink, Coke and cola beverages are synonymous with the South and originated with Southern ingenuity (Pepsi was developed in North Carolina). So, the next time you tip a glass of your favorite carbonated cola drink, remember that Yankees didn’t invent any of them and what is now considered an “American” drink originated in the South. Such is the case with most of the so-called “American” cultural icons.