As with literature, nineteenth-century American art is dominated by the North and Northern subjects. The Hudson River School, which incidentally found its greatest inspiration from the West, and most American artists of the Romantic period hailed from the Deep North. After the North won the War, the focus for the American mind shifted North and those who had carved a career from the culture of the South were lost to time. This is tragedy for American culture, both North and South.

The Southern Literary Renaissance of the early twentieth-century returned much needed attention to Southern writers, both ante and post bellum, but Southern art has remained veiled by American humanities studies.

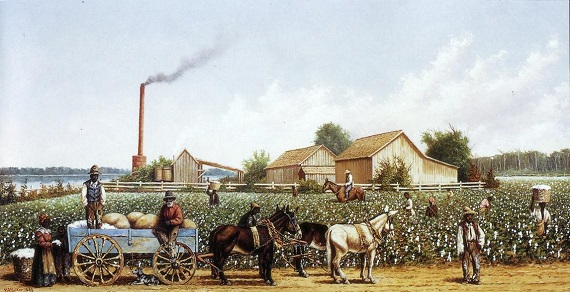

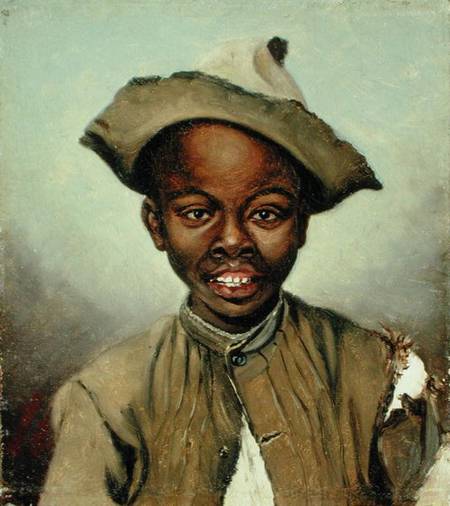

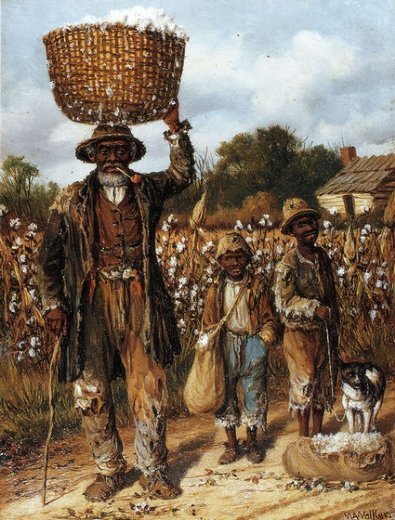

One foremost Southern artist was William Aiken Walker of South Carolina. Walker was born in Charleston in 1839 and spent several years in Baltimore as a lad but returned to South Carolina in 1848. When the War began in 1861 he marched out of South Carolina with Wade Hampton. He was wounded at Seven Pines in 1862 and spent the next two years painting war scenes from his birth city. After the War, Walker moved to Baltimore and painted scenes of the “Old South” for curious Northerners. Much of his focus was on the black community, particularly those who were impoverished by sharecropping and the lingering effects of Reconstruction. These collection of paintings represent his most interesting work. Walker died in 1921 and was buried in Magnolia Cemetery.

Like antebellum Southern literature, Walker’s paintings have a depth and element of humanity that is born in the soul of a people. He connected with his subjects, portrayed them in sympathetic reality, and displayed an admiration of place and community. They represent his people, both black and white, in a way that Northerners would be unable to recreate or connect. They were of a romantic place and time, lost by the thunder of guns and the innovations of Northern politicians. His work should be remembered and cherished as part of the Southern tradition.