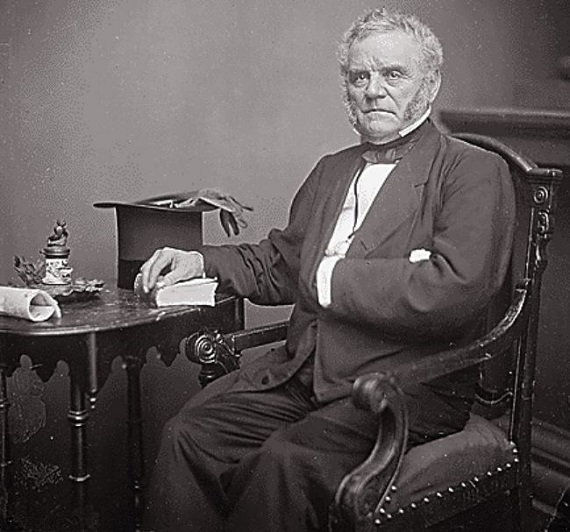

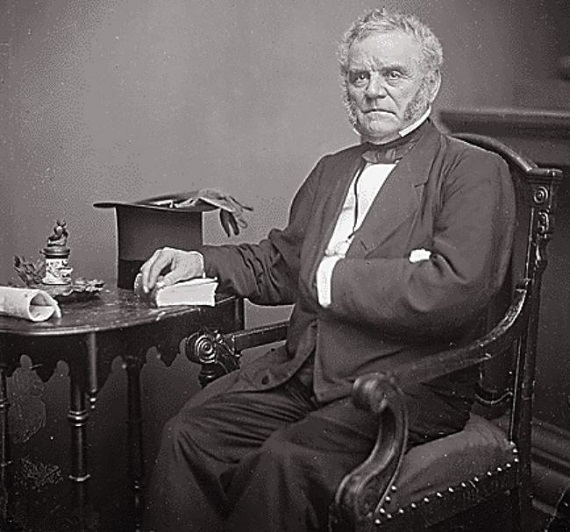

As 1861 drew to a close, Governor Thomas Hicks recorded for posterity the events of the Northern invasion and occupation of Maryland in a message he sent to members of the state’s first reconstruction era legislature, an extralegal body that would prove friendly to the Yankee regime. In defending his reluctance to authorize a special session of the previous General Assembly, Hicks acknowledges how close Maryland came to seceding.

I believed that I was thoroughly acquainted with the proclivities of a majority of the members of that Legislature. I was perfectly convinced that they desired Maryland to leap, no matter how blindly, into the vortex of Secession.

If most Marylanders had been at odds with their secession-minded representatives, as Hicks insisted, there was every reason for his welcoming a special session. Had lawmakers then moved to hold a sovereign convention, the will of Hicks’ s “loyal” populace would have prevailed against a separatist minority. His refusal to call together that legitimate legislature until the state was seized by Lincoln betrayed a belief that his constituents, from whom he received numerous death threats, were not in favor of the Yankees’ unconditional union. The “old woman in petticoats,” as one Southern Marylander referred to the governor, in trying to minimize the secessionist inclinations of the electorate and to sugar coat the Northern conquest of his state, revealed instead that Maryland was on the verge of joining the Confederacy in the fall of 1861.

In late 1860 Governor Hicks, appealing to the Southern temperament of Marylanders, nonetheless assured them that Lincoln, whom they overwhelmingly rejected, posed no threat.

Identified, by birth, and every other tie with the South, a slave holder, and feeling as warmly for my native State as any man can do, I am yet compelled by my sense of fair dealing and my respect for the Constitution of our country to declare that I see nothing in the bare election of Mr. Lincoln which would justify the South in taking any steps tending toward a separation of these States.

Jefferson Davis in his memoirs credits Hicks for his efforts on behalf of peace observing that the governor at the beginning of the secession crisis “avowed the desire, not only that… [Maryland]… should avoid war, but that she should be a means for pacifying those more disposed to engage in combat.” Less a peacemaker than a fast-talking schemer, Hicks, enraging an already angry Baltimore crowd with his pro-Union remarks, hastily reverted to his Southern patriot iteration assuring his audience that he would “suffer [his] right arm to be torn from [his] body” rather than “raise it to strike” the South.

As the Yankee armies continued to descend on his state, however, he reckoned it no longer advantageous to take the part of the “revolutionaries” and threw his lot in with the Northerners. To ennoble himself and rationalize a rank duplicity, Hicks employed the subterfuge that the Yankee invasion was a Providential blessing and that Marylanders were at cross purposes with their legislature. Hicks writes that he was…

unwilling to allow that body an opportunity so to misuse its great power; not doubting that, in imitation of the Legislature of then seceded States, it would exert that power to the great detriment of the people of Maryland.

The governor in his letter to the puppet legislature also boasts that “his” decision earlier that year to move the meeting place of the General Assembly from Annapolis to the less “disloyal” Frederick area accomplished his “full purpose”: Maryland had been kept from seceding, and “bloodshed” had been “averted from her soil.” Sharpsburg was to prove Hicks wrong on the second point. Justifying his actions, he explains that the ante-reconstruction legislature had “attempted to take, unlawfully, into its hands both the purse and the sword” in order to “plunge” their state into secession and was “deterred from doing this latter only by the unmistakable threats of an aroused and indignant people.”

But it was not “aroused and indignant” Marylanders who brought the dissolution wagon to an abrupt halt but a governor who ignored the state constitution and Yankee soldiers who arrested a sufficient number of Maryland legislators to prevent a quorum of them to assemble.

Restricted in the duration of its sessions by nothing but the will of the majority of its members… [the legislature]… met again and again; squandered the people’s money, and made itself a mockery before the country. This continued until the General Government had ample reason to believe it was about to go through the farce of enacting an Ordinance of Secession; when the treason was summarily stopped by the dispersion of the traitors.

The Governor Hicks who had once pledged that he would never betray his Southern brethren, now supported Lincoln’s war on the South. Jefferson Davis fully grasped the governor’s inconstancy and what lay at the heart of it.

It would be more easy than gracious to point out the inconsistency between his first statements and this his last. The conclusion is inevitable that he kept himself in equipoise, and fell at last, as men without conviction usually do upon the stronger side.

Hicks seems to have had in mind all along a waiting game that allowed him time to determine what course served his interests. Confederate general and fellow Marylander Bradley Johnson said of the governor that he was a “shrewd” and “sharp” man who “knew that Maryland was as ardently Southern as Virginia.” Johnson believed Hicks “wanted to save Maryland to the Northern States” because the governor calculated that Maryland would become a more “conspicuous power” in a Northern rather than Southern nation.

Hicks’s name should be as well-known as Grant’s or John Wilkes Booth’s because there is hardly a more fascinating—or important—figure in American history than the governor, a weak, indecisive fool, some revisionists insist, the voice of reason according to other rewriters of the past. But Hicks was an arrogant, word-parsing opportunist and a petty tyrant with big ambitions who, if he had acted in accordance with the wishes of the people of his state, would have contributed greatly to a Southern victory in the War of Secession. Because he was unprincipled and self-absorbed, his besieged Maryland eventually fell to the Union and became “a miserable and disgraced appendage” of the North. Hicks left Maryland bound to a foreign land, then quickly faded into the obscurity he sought so desperately to avoid.