This essay was first published at Unz Review on November 23, 2014.

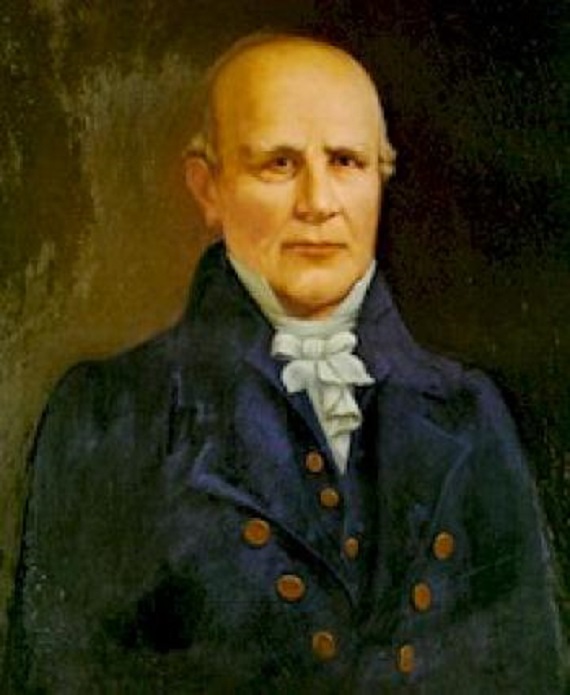

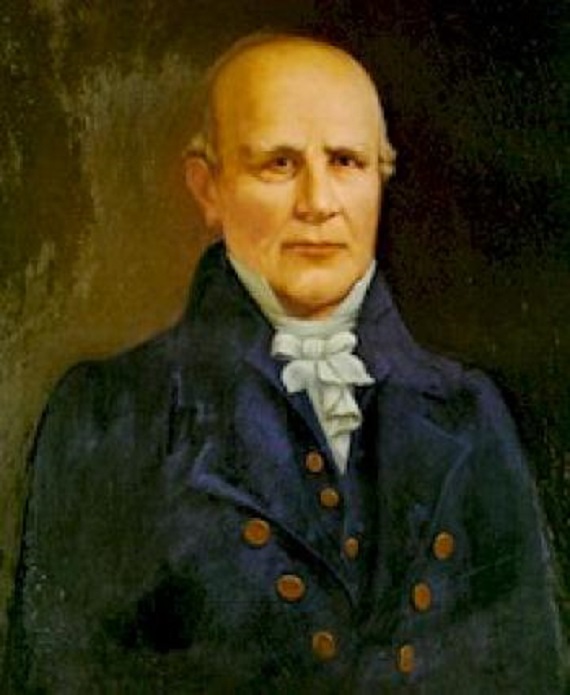

Back in 1975 the Warren County [N.C.] Historical Association initiated a comprehensive project to study the life and legacy of Nathaniel Macon. As a part of this project, both archaeological and architectural studies of his old Buck Spring plantation, near the Roanoke River, were commissioned. Working with the professional staff of the North Carolina Division of Archives and History, the Macon project had, it was proposed at the time, a longer range potential objective: a possible state historic site to honor North Carolina’s most historically significant political leader, whose legacy and philosophy and character influenced not only generations of Tar Heels, but also a host of very illustrious Southerners, their thinking, and the very manner in which they lived their lives and viewed the society around them.

Working with architectural historians and experienced archaeologists, I was commissioned to prepare both a chain of title for the Buck Spring site, as well as a detailed written history of Macon and his life. All of this would be organized in a major report that might be used to justify the future creation of an important historic site, sadly never realized, giving credit finally to this giant of North Carolina and American history. At that time I was finishing up a doctorate in graduate school. A few years earlier Macon and his underappreciated significance to the history of this nation had figured in my MA thesis presented at the University of Virginia. I was amazed at the incredible importance “the Squire of Buck Spring” had had in the new American nation, and, more interestingly, the influence he had on such later and much better known figures as John C. Calhoun and President John Tyler.

Yet, in 1975 Macon was basically unknown, and his role and importance in American history, so appreciated before the War Between the States, were largely ignored or glossed over.

Quite a bit of this contemporary ignorance must, I think, be attributed to Macon’s philosophy. He was, indeed, to quote his contemporaries, “the father of states’ rights” and the figure most critical in the actual development and survival of the states’ rights philosophy that still, in some ways, percolates in American politics.

Above all, it was Macon’s probity of character and his steadfast devotion to principle that won him general admiration from across the entire spectrum of antebellum political opinion. Leaders as diverse as Presidents John Quincy Adams and John Tyler expressed great admiration for Macon; many attempted to tie in their own views, even those ideas that seemed at odds with Macon’s, to those of the Squire of Buck Spring. After leaving the U. S. House of Representatives in 1816 and being elevated to the United State Senate by the North Carolina General Assembly, Macon’s influence only grew and became more pervasive, especially in the South.

It was his role during the debates over the Missouri Compromise that signaled the emergence of a genuine states’ rights philosophy. But it was not just that hotly debated issue that occupied his attention. Questions regarding internal improvements, the establishment of a national bank, and the general role of the Federal government in questions hitherto considered the concern of states, also occupied him. For him all such issues, and increasingly the contentious issue of slavery, were a part of a larger question, that of how the Constitution was to be interpreted.

As early as March 1818 he wrote to North Carolina congressman Bartlett Yancey as follows:

I must ask you to examine the Constitution of the United States….and tell me, if Congress can establish banks, make roads and canals, whether they cannot free all the slaves in the United States?….We have abolition, colonization and peace societies–their intentions cannot be known; but the character and spirit of one may without injustice be considered that of all. It is a character and spirit of perseverance bordering on enthusiasm, and if the general government shall continue to stretch its powers, these societies will undoubtedly push it to try the question of emancipation….

With the debate over Missouri looming, Macon wrote to Yancey again, in April 1818:

If Congress can make canals they can with more propriety emancipate. Be not deceived, I speak soberly in the fear of God and the love of the Constitution. Let not the love of improvement or a thirst for glory blind that sober discretion and sound sense, with which the Lord has blest you. Paul was not more anxious or sincere concerning Timothy, than I am for you. Your error in this will injure if not destroy our beloved mother, North Carolina, and all the South country. Add not to the Constitution nor take therefrom. Be not led astray by grand notions or magnificent opinions. Remember that you belong to a meek State and just people, who want nothing but to enjoy the fruits of their labor honestly and to lay out their profits in their own way.

In early 1819 the actual debate in the Senate over the admission of Missouri to the union commenced, and, as Missouri was a territory where slavery existed, that contentious question became central to the debate. A resolution–a compromise–put forward by Senator Jesse Thomas of Illinois proposed admitting Maine as a “free” state and Missouri as a “slave” state but prohibiting slavery in the rest of the Louisiana Purchase north of latitude 36 degrees, 30 minutes.

Many Southern leaders, including the then Secretary of War John C. Calhoun, were prepared to go along initially with the compromise, but Macon, singularly, rose to oppose it. And it was in his famous Senate speech on the question that heralded the birth of a full-fledged “Southern philosophy.” The speech deserves to be quoted at length:

All the states now have equal rights and are content. Deprive one of the least right which it now enjoys in common with the others and it will no longer be content….All the new states have the same rights that the old have; why make Missouri an exception? Why depart in her case from the great American principle that the people can govern themselves? All the country west of the Mississippi was acquired by the same treaty, and on the same terms and the people in every part have the same rights….The [Thomas] amendment will operate unjustly to the people who have gone there from other states. They carried with them property [slaves] guaranteed by their states, by the Constitution and treaty; they purchased lands and settled on them without molestation; but now, unfortunately for them, it is discovered that they ought not to have been permitted to carry a single slave….Let the United States abandon this new scheme; let their magnanimity, and not their power, be felt by the people of Missouri. The attempt to govern too much has produced every civil war that ever has been, and will, probably, every one that ever may be. [Italics added]

And finishing with an amazingly prescient vision of the future, Macon continued:

Why depart from the good old way? Why leave the road of experience to take this new one, of which we have no experience? This way leads to universal emancipation, of which we have no experience….A clause in the Declaration of Independence has been read, declaring “that all men are created equal.” Follow that sentiment, and does it not lead to universal emancipation? If it will justify putting an end to slavery in Missouri, will it not justify it in the old states? Suppose the plan followed, and all the slaves turned loose, and the union to continue, is it certain that the present Constitution would last long?

The debate over the Missouri Compromise marked a significant turning point in American history and, eventually, in the diverging views of the leaders of both the South and the North. Although Macon had been engaged in a losing effort to block the compromise, his forthright and clear-sighted defense of strict constructionism and his beloved “South country” had singled him out as a prophet. Not many years after his remarkable intervention in the Missouri debates, a whole generation of Southern congressmen and political leaders would acknowledge him as the intellectual father of states’ rights. In 1821 a chastened Thomas Jefferson, who had also foreseen how the crisis would affect the nation—Jefferson, who termed the stark reality made visible by the debates as “a fire bell in the night”—called Macon “the Depositor of old & sound principles,” and wrote him: “God bless you & long continue your wholesome influence in public councils.”

Despite his staunch support for states’ rights and “old republicanism,” Macon was greatly esteemed by a wide variety of American political leaders. President John Quincy Adams, a man of almost diametrically opposite views, in his Memoirs described Macon as “…a stern republican…a man of stern parts and mean education, but of rigid integrity, and a blunt, though not offensive, deportment…one of the most influential members of the Senate. His integrity, his indefatigable attention to business, and his long experience give him a weight of character and consideration which few men of superior minds ever acquire.” In 1828 it was widely rumored that Adams, despite differences with Macon, considered him as his potential vice-presidential choice.

In 1824, after the illness of leading states’ rights presidential candidate, William H. Crawford, Governor George M. Troup of Georgia put forward Macon as a candidate for president: “I know of no person who would unite so extensively the public sentiment of the southern country…as yourself.” In 1825 Macon received twenty-four electoral votes for the vice-presidency. In 1826 and 1827 he was elected President Pro-Tempore of the United States Senate.

As he approached the end of his long career, recognition of his significant role in American history and political development came from some of the most significant voices of the time. From Calhoun, John Tyler, and Thomas Hart Benton came encomiums and words of admiration and the recognition that Macon had played a pivotal role in the history of the first sixty years of the American nation.

While many readers in our modern age may think that Macon’s most pointed comments deal with the institution of slavery, it was not defending the “peculiar institution” that was at the base of his philosophy. Indeed, his stringent commentary on the Federal bank and government support for internal improvements equally reflect a states’ rights consistency and integrity. Slavery, because Macon recognized it as a particularly dangerous lynchpin for the American nation, certainly occupied a salient part of his commentary. But the greater issue for him was the growing power and control of the Federal government and the eventual destruction of the older Constitutional system erected by the Founders.

In 1835, in his last major public role, Macon was elected to preside over the North Carolina Constitutional Convention. While he made few interventions, he generally opposed changes to the state constitution. For him, “all changes in government were from better to worse.”

In June 1837 Macon summoned his doctor and the undertaker and paid them in advance. He died on June 29 that year, at Buck Spring. In a simple ceremony on his plantation he was interred, attended by grieving slaves, with whom he had worked side-by-side in his fields. He instructed his executor and son-in-law, the Honorable Weldon N. Edwards, that no monument mark his grave, but that a pile of smooth stones be placed upon the site.

His epitaph he spoke eighteen years earlier, in Congress: “The attempt to govern too much has produced every civil war that ever has been, and will, probably, every one that ever may be.” Macon understood and clearly foresaw the results of the destruction of liberties and the erosion of states’ rights and the emergence of an all-encompassing Federal government.

The pile of stones at Buck Spring remains, as does the philosophy that Macon first enunciated, despite the accomplishment of the shattering prophecy he uttered. And, now, it is up to another generation to attempt to retrieve and recover the Founders’ vision.

This essay serves as the Foreword to a new (2014) printing of Congressman Weldon N. Edwards’ Memoir of Nathaniel Macon of North Carolina , originally published in Raleigh, 1862, and now republished by Scuppernong Press, Box 1724, Wake Forest, North Carolina 27588; copies may be obtained directly via the web site, www.scuppernongpress.com