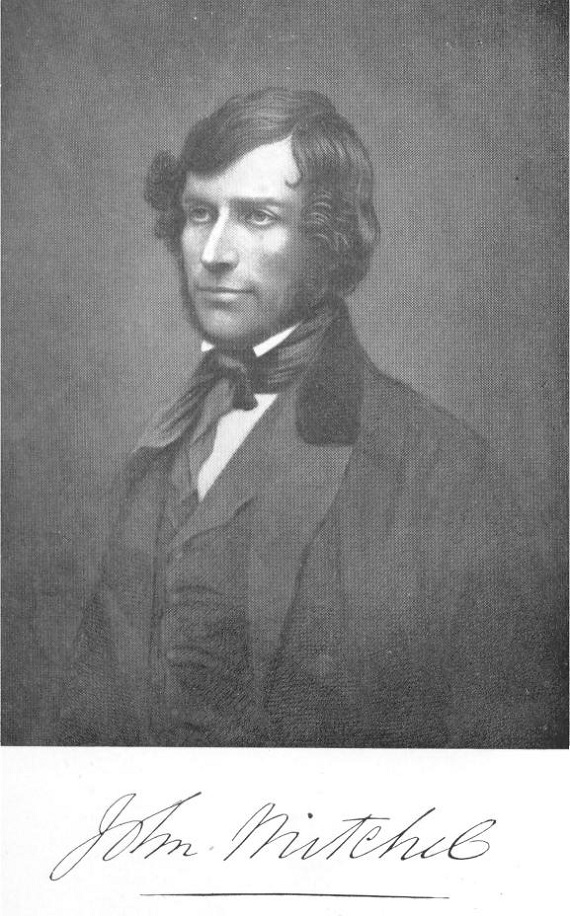

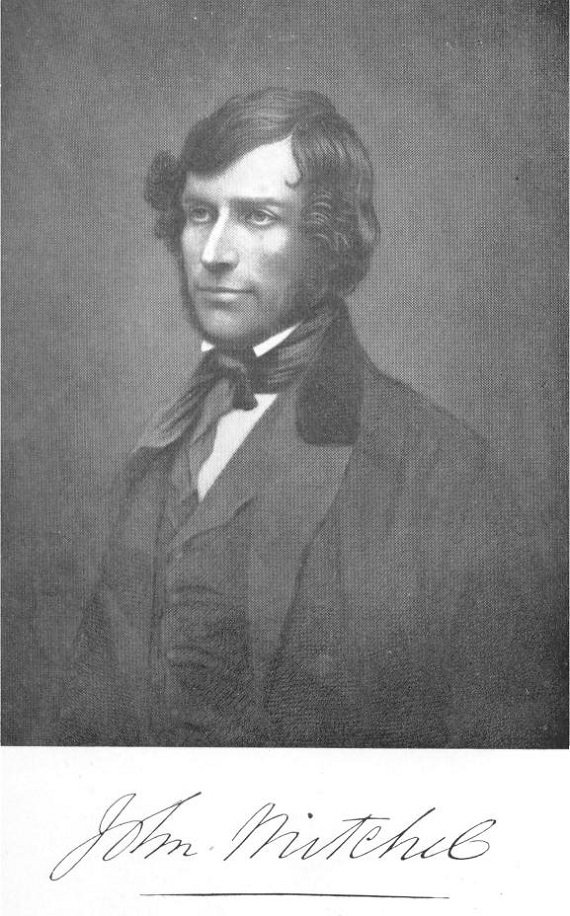

John Mitchel (1815-1875) was a fiery Irish nationalist who was convicted of treason by the British in 1848 and transported first to Bermuda and then to a penal colony in Australia, from which he escaped in 1853. After Mitchel and his family settled in America, he continued his nationalist activism by founding a radical Irish newspaper in New York, denouncing British policy in his native country and worldwide. Scornful of Victorian ideas of social, scientific, and technological progress, he wrote in his famous, influential Jail Journal, “It is altogether a new thing in the history of mankind, this triumphant glorification of a current century…no former age, before Christ or after, ever took pride in itself and sneered at the wisdom of its ancestors; and the new phenomenon indicates, I believe, not higher wisdom but deeper stupidity.”

Mitchel admired Southerners, whose agricultural civilization he saw as a haven from modern industrialization. In 1855 his sympathy for the Southern cause took him to Tennessee, where he began another newspaper, the Southern Citizen. “I prefer the South in every sense,” he wrote in a letter of 1857, adding, “I do really believe its state of society to be more sound, more just, than that of the North.” He detested abolitionists, infuriating them with his pro-slavery stance, and he railed against Northerners for their materialism and hypocrisy, equating the North’s efforts to impose its will on the South with Great Britain’s oppression of the Irish.

When the war came, three of Mitchel’s sons enlisted in Confederate service, and two gave their lives in battle. The youngest, Private William Mitchel (born 1844), received a mortal wound in July 1863 while carrying his regiment’s flag in Pickett’s Charge during the Battle of Gettysburg.

The eldest of John Mitchel’s sons, John C. Mitchel, was commissioned as a lieutenant in the 1st Regiment of South Carolina Artillery and assigned to Fort Moultrie near Charleston. He was soon promoted to captain, and in January 1863 took part in the capture of the Federal gunboat Isaac Smith operating on the Stono River. Regarded as a promising and distinguished officer, he was recommended for promotion to the rank of major.

On May 4, 1864, still a captain, Mitchel was put in command of Fort Sumter. In July of that year, during the third great bombardment of the fort, he was mortally wounded by the explosion of a mortar shell while observing the enemy’s movements from an earthwork parapet. While still conscious he was taken down to the hospital, where he lingered for about four hours in extreme pain. Just before his death, one of his fellow officers asked him what could be done for him, and he replied, “Nothing, except to pray for me.” His last words, as recorded on his epitaph, were, “I willingly give my life for South Carolina. Oh! that I could have died for Ireland!” The stone coping outlining Captain Mitchel’s grave plot in Magnolia Cemetery in Charleston resembles the shape of a parapet of Fort Sumter.

After the war John Mitchel, Sr. returned to New York and took on the editorship of a Democratic newspaper. He denounced the triumphant, vindictive North for heaping “ingenious and intolerable humiliation” on the South, and for the expression of such sentiments, he was arrested in June 1865 and confined at Fort Monroe. One of his fellow prisoners there was Confederate President Jefferson Davis, whose cruel imprisonment Mitchel called “one of the blackest villainies known to history.” Mitchel was treated so harshly during his first two months at Fort Monroe that a prison physician who examined him warned the authorities that he would die if not allowed exercise and better food. Though conditions improved for Mitchel after this, his health was irreparably damaged.

John Mitchel claimed the distinction of being the only man ever held as a political prisoner by the United States and British governments, both of which he despised, writing: “And these two governments, we are told, are the very highest expression and grandest hope of the civilisation of the nineteenth century…They are both in the wrong: but then, if I am able to put them in the wrong, they are able to put me into dungeons.”

He was released from Fort Monroe in late October 1865, but continued to denounce the Radical Republican dominated government in his newspaper the Irish Citizen. When a friend told him that his hatred for Yankees was blinding him to humanity’s future, Mitchell replied in a letter, “Poor humanity! If it depends for its future upon the Yankees it is going to have a damned bad time.”

Though not optimistic about Home Rule for Ireland, John Mitchel returned to his native country in 1875 and was elected to serve as a member of the British Parliament, representing the county of Tipperary shortly before his death in that year.

In his eulogy on John Mitchel, South Carolina congressman Michael P. O’Connor said of him:

John Mitchel never regretted anything he ever did; he was sincere in his convictions, and never quailed in their support; and, though the ploughshare of war had made a horrid furrow over the hearthstones of the South, and her people were sunk in sorrow and humiliation; and grim power, reckless of constitutional restraints, had raised its awful front, and quaking millions bowed down in awe before it; he, undaunted to the last, never forgot his love, nor relinquished his devotion to the South.