A Gentleman in Charleston and the Manner of His Death by William Baldwin. University of South Carolina Press. 2005. Hardcover. 203 pages.

A friend and I were talking recently, and she happened to remark to me that she had read somewhere (the source remained undisclosed) that Atlanta was the cultural capital of the South. No sooner had she spoken did she realize the terrible anomaly of what she had just said. We eyed each other skeptically. More than likely she had picked up such a nugget of perspicacity from the Internet or from perusing the pages of the national edition of some news organ printed much above the Mason Dixon line. Or, most dismaying of all, perhaps she had seen such an ill-pronounced judgment in a local newspaper, one clamoring to show how in lockstep it is with contemporary thinking. In any event, she knew better. The both of us knew better.

As lifelong South Carolinians we knew there could be only one serious contender for such a lofty title, and no, it wasn’t Savannah either, as much as the both of us love and admire that city by the shore. Savannah’s stock has certainly risen in the last few years with its being celebrated by a dubious if highly entertaining “non-fiction” book and its being the home base of a currently popular cooking matriarch on the Food Network. No, despite its ample charms, so far not too much despoiled by tourism, Savannah must take the runner’s up ribbon in deference to the only city which can claim the title of “cultural capital of the South.” The bearer of the crown, of course, is Charleston. (South Carolina, of course, so as not to give West Virginia readers any false hope.)

True, Charleston has never hosted the Olympics, nor has it been the scene of the playful, civil “Freaknik” bacchanals which descend upon Atlanta every year and which no doubt caused the anonymous writer mentioned above to confer the title of “Southern cultural capital” on the place. Charleston is multi-cultural but not in a way which calls attention to itself. Its lack of ostentation, its dignity if you will (a term almost embarrassing to use in an age when so little dignity attains), makes it more distinctly Southern than any other major city that comes immediately to mind – that and the fact that it just happens to be the most beautiful city on the face of the earth.

Such quiet virtues, however, have perhaps made Charleston less than an ideal setting for literary endeavor. True, the city was at the center of international attention in 1989 when Hurricane Hugo blew through, but no first rate work of prose emerged from that conflict. One needs to go back many years to find a time when Charleston was the locale for an important novel, short story, or poem, to the work of William Gilmore Simms, Josephine Pinckney, Dubose Hayward, etc. (For an excellent and thoroughly non-academic consideration of Charleston in its literary heyday, please consult David Aiken’s Fire in the Cradle: Charleston’s Literary Heritage.) In recent years it has served as the playground for such confection makers as Alexandra Ripley, Dorothea Benton Frank, Anne Rivers Siddons, and Pat Conroy. Josephine Humphreys, who produces intermittently, is about the only first-rate literary artist who still uses Charleston as the setting for her work. There is also William Baldwin, whose third novel, A Gentleman in Charleston and the Manner of His Death, is the subject of the present review.

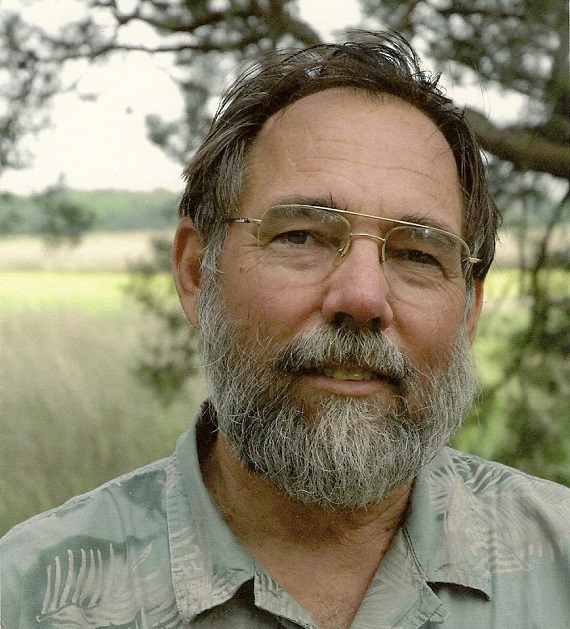

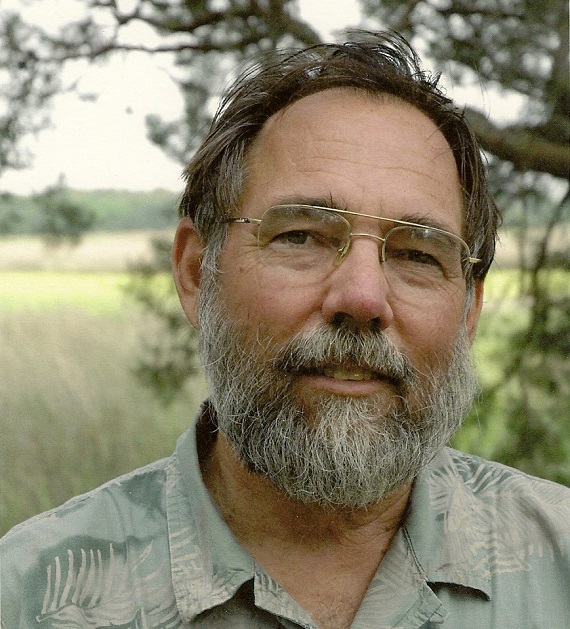

Baldwin would seem an ideal chronicler of the Holy City and its surrounding environs. After all, according to his biography, he is a lifelong native of the South Carolina low country who saw life as a commercial fisherman and building contractor before turning to literature. His first novel, The Hard to Catch Mercy, published in 1993, when Baldwin was past fifty, earned its author the Lillian Smith Award for Fiction. His follow-up novel, The Fennel Family Papers, appeared two years later. Each has at its center an eccentric family and is told in a fragmented narrative style featuring interlocking stories. The same can be said of A Gentleman in Charleston. For its first hundred or so pages, the novel meanders, depositing disparate elements at the reader’s feet and often trying his patience. Fortunately, Baldwin is skillful enough a storyteller to be able to weave these elements together eventually into a fairly satisfying whole.

The book is set in Charleston, obviously, in the years following the War Between the States and has as one of its themes honor, but other than that, it would be hard to classify this as a “Southern novel.” In fact one more quickly thinks of figures such as Henry Green and Nabokov in comparison. Like Green’s novel Loving, Gentleman views the foibles of a prominent family and its hired help, in this case a beautiful nanny named Helene, whose physical comeliness leads to the demise of the title character, David Lawton, a British expatriate and “Civil War” hero who also edits Charleston’s leading newspaper and has accrued a number of enemies through the years. It is in defending Helene’s honor (while tending his own ambivalent feelings toward the girl) that Lawton dies, a death foretold by his haunted, perhaps mentally disturbed wife Rebecca. There are a number of competitors for Helene’s affections, among them a young man who may or may not be Lawton’s illegitimate son.

Baldwin relates all this with Nabokovian playfulness, word play, time shifts, and an intrusive narrator who would give Henry James fits. As with Nabokov, concern with language is paramount. Indeed the book opens with the sentence “I know the power of language to destroy.” One word effectively ends the life of the “most powerful man in the South.”

The style is so stiffly antiquated it appears new; it apes the overheated prose in the Victorian novels the characters in A Gentleman read, but it is not for the impatient reader looking for a quick read between television shows. One grows tired of the novel at times, until the narrative strands begin to cohere and show pattern. And the book’s erotic candor makes it unsuitable for the very young and sensitive.

Still, it is hard not to like a book featuring a scene in which Abraham Lincoln in Richmond is greeted by a choir of ragamuffins and prostitutes. Oh, the symbolism.