After my last trip to Gettysburg with Kent Masterson Brown, I could hardly wait for Sharpsburg. The experience did not disappoint. Kent was as congenial as ever, warm with his longtime followers (a group of fellow Kentuckians known as the ‘I Corps”) and welcoming to newcomers – many of whom, I was happy to discover, came from the Abbeville Institute. Kent was also the walking, talking encyclopedia of history that I remembered – and it is not merely memorized. For instance, during the opening ceremonies, Kent asked everyone to share a little about themselves, particularly if they had an ancestor at the Battle of Sharpsburg or in the Civil War at all. When it was my turn, I said that my Confederate ancestors were in the 44th Tennessee, which was not at Sharpsburg but in the Western Theater. “Ah, yes,” replied Kent. “Bushrod Johnson’s division.” Folks, he ain’t playin’.

Like last time, I decided to share some of the themes of the tour:

It Wasn’t and It Was

The Civil War, of course, is a misnomer: a civil war is when multiple factions fight for control of a government, yet the South was fighting for freedom from a government – the unchecked, uncontrollable leviathan state which, quipped Kent, given the current state of affairs, it was a shame the Confederates did not descend upon, after all. Donald Livingston, chairman of the Abbeville Institute, conveys the enormity of the war with a present-day hypothetical:

“Suppose the legislature of California should today call a convention of the people of the state to vote up or down an ordinance to secede from the Union and it was later ratified by the people in convention. Suppose Oregon and Washington should do the same, and within three months eleven contiguous states had joined to form a Pacific federation. The federation, then, recalls its senators and representatives and sends commissioners to Washington to negotiate payment of federal property and its share of the national debt.

“In response, the administration in Washington refuses to see the commissioners. It argues the states are not political societies but administrative units of the national government; that the votes of the people in state constitutional conventions are null and void. A military force is assembled to invade and coerce the seceding states back into the Union. After nearly two years of fighting when it becomes clear that the federation is determined to maintain its independence and Washington might lose the war, the administration turns to total war, directing its forces against civilians in hopes of demoralizing the enemy in order to quickly end the war.

“Eventually the Pacific federation is defeated. Its cities laid waste, a quarter of its men of military age dead, some 60 percent of its capital destroyed, its public debt repudiated, and its currency worthless. The total number of battle and civilian deaths (the latter almost exclusively in the Pacific federation), is in the range of 10 million. Washington acknowledges this was a high price to pay to keep all 50 states under central control, but gives thanks to God that the Union was preserved.”

“Can there be any doubt that most thoughtful people in the world today would judge the United States…to be guilty of a crime against humanity?” asks Livingston in conclusion. “Yet that was in all essentials what happened in the War of 1861-1865.” The unvarnished truth is that it was conquest, not civil war.

At the same time, however, the war was a civil war in the sense that it was a war of “brother against brother,” especially among the commanders, who had preexisting relationships from the old army. Kent illustrated this tragedy throughout the tour.

Daniel H. Hill was a Confederate general who had graduated from West Point, fought in the Mexican-American War, and taught as a professor of mathematics at what is now Washington & Lee University and Davidson College (he wrote an algebra textbook which is sprinkled with word problems poking fun at Yankees, e.g. calculating the rate of travel of retreating Indianans, the price charged by a cheating Cincinnatian, the amount of witches executed in Salem, and the number of “old maids, childless wives, and bedlamites” at a feminist conference in Syracuse). John Gibbon was a Federal general who had graduated from West Point and fought in the Mexican-American War. Hill and Gibbon were close friends, so much so that Gibbon had been Hill’s best man in his wedding. A native North Carolinian, Gibbon also had three brothers serving in the Confederate gray. However, on September 14, 1862, Hill and Gibbon faced one another at South Mountain, where Hill’s division held out for an entire day against an onslaught of three Federal corps.

Henry W. Kingsbury was a Federal colonel who graduated from West Point the year that the Civil War erupted. He was considered one of the institute’s most promising cadets. David R. Jones was a Confederate general who had graduated from West Point and was known as “Neighbor” among his men for his friendliness. Kingsbury and Jones, however, were brothers-in-law, and on September 17th, they faced each other at Burnside’s Bridge, where Jones defended high ground against Kingsbury’s gallant charge. Kingsbury died that day in battle and Jones later died from a mysterious heart ailment which some suspected was brought on by the fear that he was responsible for his brother’s death.

Hearing these stories, I was haunted by John Taylor of Caroline’s early warning that Northerners and Southerners were meant to be friends, but that a ruling class in Washington, D.C. – “an aristocratic oppressor of them all” – had made them enemies. Taylor observed this emerging rift in 1820, when Northern and Southern brothers were only spilling ink against one another, but he predicted that they would soon be spilling blood.

“Doggone Determination”

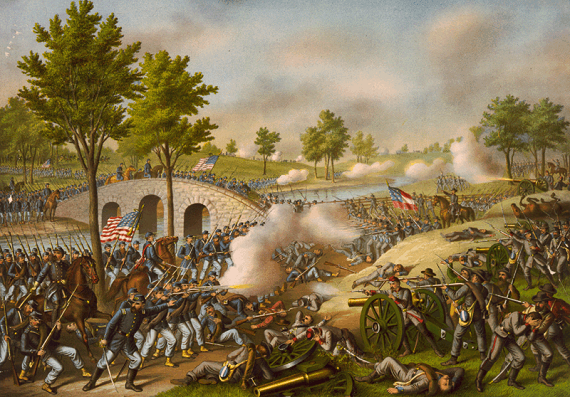

At the time of the Battle of Sharpsburg, Lee’s men had been fighting long and hard for half a year. They had resisted the Federal advance in the Peninsula Campaign, pushed them back in the Seven Days Campaign, and smashed them at Second Manassas. The Army of Northern Virginia was physically and psychologically exhausted and required time to rest and resupply. Instead, Lee, sensing an opportunity to win the war, crossed the Potomac River and opened a new campaign.

The fact that the Confederates could march and fight at all was astounding, yet march and fight – and win – they did. “It is beyond all wonder how such men as the rebel troops can fight as they do,” remarked a Federal surgeon. “That, filthy, sick, hungry, and miserable, they should prove such heroes in fight, is past explanation.”

No Confederate represented what Kent called this “doggone determination” better than General John B. Gordon, who survived five gunshot wounds leading a brigade of Alabamians at the Bloody Lane. Standing where Gordon once stood, Kent read a harrowing account of the fight from Gordon’s memoir, which was so fierce that when the smoke cleared, corpses literally covered the earth. At that spot in that moment, Gordon’s dark comedy and pathos brought the battle to life again.

Redefining the War

The Sharpsburg museum was interesting and properly respectful, including a history of the site’s preservation (incredibly, it was watched over by the local community for a century without any government interference), and artifacts such as the old uniform of Henry Kyd Douglas (Stonewall Jackson’s aide, whose magnificent home overlooking the Potomac was visible from our lodgings).

There was, of course, the obligatory adoration of the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared slavery abolished in the Confederacy, where Lincoln had no authority, but preserved slavery in the Union, where Lincoln had authority. Lincoln’s proclamation supposedly redefined the war to be a crusade for the Union as well as abolition. This modern interpretation of the Emancipation Proclamation is mostly wishful, however. Emancipating slaves – which took the form of relocating them to “contraband camps” where countless died from disease and starvation – was simply a tactic in Lincoln’s overriding goal of preserving the Union. Lincoln had realized that slavery was a tremendous asset to the Confederacy and that emancipation would deprive her of a vital source of labor and thus undermine her economic structure. At the same time, it would discourage Britain and France, who were preparing to recognize the Confederacy, from getting involved.

As Lincoln explained at the time, emancipation was not a grand statement of moral principle, but “a practical war measure, to be decided upon according to the advantages or disadvantages it may offer to the suppression of the rebellion.” Indeed, Lincoln doubted that the courts would uphold the proclamation after the war, and bargained with the Confederates to trade slavery for national reunification. When told that emancipation would rally flagging Northern morale, Lincoln replied, “We already have an important principle to rally and unite the people in the fact that constitutional government is at stake” (Lincoln’s idea of “constitutional government” being founded on the force of arms rather than the consent of the governed). Thus, when Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, he remained consistent with his earlier statement to abolitionist editor Horace Greeley:

“My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it…What I do about slavery, and the colored race, I do because I believe it helps to save the Union; and what I forbear, I forbear because I do not believe it would help to save the Union.”

One way in which the Emancipation Proclamation did redefine the war, however, was in its brutality. Previously, the official policy of the Federal armies had been to respect the person and property of the civil population, but now Southern civilians were to be expropriated and dislocated. “There is now no possible hope of reconciliation with the rebels,” General-in-Chief Henry W. Halleck wrote to General Ulysses S. Grant. “There can be no peace but that which is forced by the sword.” Grant concurred in his reply to Halleck. “Rebellion has assumed the shape now that it can only terminate by the complete subjugation of the South,” wrote Grant. “It is our duty to weaken the enemy, by destroying their means of subsistence, withdrawing their means of cultivating their fields, and in every other way possible.” Emancipation was simply a subset of this larger policy of total war. “The character of the war will be changed. It will be one of subjugation and extermination,” admitted Mr. Malice-Towards-None himself. “The South must be destroyed and replaced by new ideas and propositions.” Ideology was to replace civilization.

Kent described the predicament facing Northern commanders, struggling to balance the objective of military reunification with the hope of political reconciliation. “Were they to crush their brothers?” asked Kent. “Is this how they were to preserve the Union?” Lincoln answered yes.

And the Winner is…

Sharpsburg is commonly described as a “tactical Confederate victory” and a “strategic Federal victory,” a confusing distinction to say the least. Kent’s assessment was much clearer: the battle was a clear Confederate victory (Lee defeated everything that was thrown at him) but the campaign was a clear Federal victory (Lee was forced to withdraw from Maryland).

Kent marveled at what the out-numbered, under-supplied, and exhausted Confederates were able to achieve at Sharpsburg. According to Kent, it was the cause for which they fought that sustained them. “And that cause was not what is claimed today,” he continued, alluding to the notion that Confederates were fighting for slavery, “but had to do with the fact that their country was invaded.” As a Georgian killed at Sharpsburg had written home to his wife, it would be “glorious” to die “in defence of innocent girls & women from the fangs of the lecherous Northern hirelings…who are indeed engaging in this strife for ‘beauty & booty.’”

I hope to see y’all at Kent’s next tour at Vicksburg!