Sometimes opponents of nullification base their opposition on the claim that Jefferson and Madison’s blueprint against federal overreach could only have applied to a unique situation present in 1798. The Alien and Sedition Acts, they say, represented an extreme situation for which there was an applicable remedy, but those ideas have died and can never be invoked again. They say that the compact view of the Constitution is irrelevant, because the federal government has already usurped too much authority.

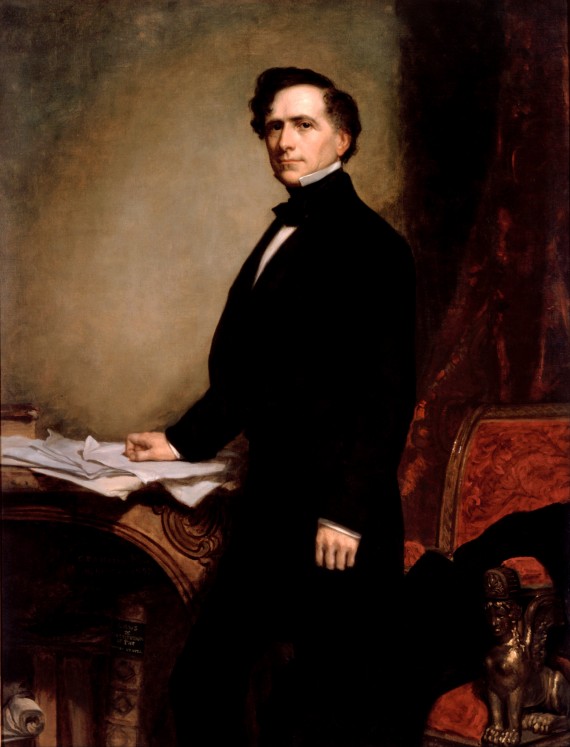

Over 50 years after the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions of 1798, an underappreciated President proved this mentality to be a faulty one.

In 1854, a bill crossed the President’s desk which would have provided federal benefits, lands, and facilities for insane peoples. The bill was fiercely defended by its proponents as a bill that would provide needed assistance to those who suffered from illness and support to the most vulnerable in society.

President Franklin Pierce responded by vetoing the bill. He crafted a veto message which explained his reasoning:

“With this aim and to this end the fathers of the Republic framed the Constitution, in and by which the independent and sovereign States united themselves for certain specified objects and purposes, and for those only, leaving all powers not therein set forth as conferred on one or another of the three great departments — the legislative, the executive, and the judicial — indubitably with the States.”[1]

Pierce also argued that the United States should not commit itself to the cause of social welfare, which he rightly understood was the responsibility of states and local governments. Pierce’s stance was strong enough to ensure that no other social welfare program would be adopted in the United States for about 70 years. At the time, the desire to see unconstitutional law defeated was a strong moral and ethical argument that could not be historically refuted.

The veto message referred to the general government as the “creature of the States,” and recognized that the colonists were “the inhabitants of colonies distinct in local government one from the other before the Revolution. By that Revolution the colonies each became an independent State.”[2]

Pierce vetoed eight other pieces of legislation, using the same justification: the bills being proposed did not fall within the scope of the enumerated powers delegated to the federal government. Therefore, none of them could even be considered.

Where once there were Presidents that refused to endorse blatantly unconstitutional policy, today we have Presidents that refuse to acknowledge any limitations to their own authority. Where we used to have executives that respected separation of powers and the legislative process, we now have executives that try to supplant it through executive order.

Another contribution Pierce made was a response to the common tendency of Presidents to step beyond the bounds of the Constitution. When the writ of habeas corpus was suspended by the Lincoln Administration under Secretary of War Edwin Stanton in 1863, Pierce replied accordingly:

“Is not this the worst form of despotism? Martial Law declared throughout the land, with the additional appendage of a band of prejudiced, passionate, irresponsible, abolition office holders, constituted as a special corps of accusers! What ideas must this Secretary have of the unlimited and unrestrained Central power when he assumes thus to impose duties upon and give instructions to “Superintendents or chiefs of police of any town City or district”? Let there be no more talk of Sovereign States, of Constitutional Rights—of trial by Jury—of legal protection for persons & property.”[3]

Considering the policy of the Lincoln Administration particularly dubious, Pierce lamented that its actions were ones that “have nullified the Constitution.”[4] Two years later, Pierce scolded the President for instituting a draft and arresting Democratic opponent Clement Vallandigham on arbitrary grounds.

Most modern historians have rated Pierce very poorly, pontificating that the President was a “do-nothing” that sat by and watched a divisive population grow even more divided. To the contrary, Pierce respected the Constitution as ratified and not as it was muddled by federal judges and legal precedents.

Academia has largely perpetuated the view that Pierce was a catastrophe, enunciating the perceived failures of the man. Historian David Holzel noted in the Wall Street Journal that “he was a complete failure as president.”[5] Holzel explained that “the only important thing that happened during his administration was the first perforated postage stamps were made.”[6]

A 2013 New York Times poll of historians ranked Franklin Pierce as the 42nd best President in United States history, placing him third from the bottom of the list.[7] A compilation of twelve different surveys also found Pierce 42nd.[8] The drinking problems that plagued Pierce late in his life are often highlighted while his accomplishments are rarely cited. Unsurprisingly, Pierce is despised by the powers that be.

In reality, Pierce shunned those wishing to grant government unlimited authority over what it had never claimed before. He stood up against unconstitutional acts when it was unpopular to do so. He did so without regard to his personal reputation. In effect, Pierce carried the banner of Jeffersonian tradition.

The most beneficial aspect of nullification is that it the greatest insurance policy for a free society. We live in an age where today’s Presidents were not formed from the same mold as Pierce. As individuals, we cannot simply count on Presidents to revere the Constitution and act on its behalf to curtail government expansion. The states must take their own authority, guaranteed to them in the ratification conventions and defined in the Jeffersonian tradition. They should follow Pierce’s example and refuse to waver on these issues, even if their personal reputations suffer as a result.

References:

[1] “Franklin Pierce, Veto Message (May 3, 1854),” The American Presidency Project, September 14, 2013; available at http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=67850[2] Ibid.

[3] Franklin Pierce to John H. George, August 11, 1862, Pierce Papers, Library of Congress.

[4] Ibid, 332.

[5] Cynthia Crossen, “Historians Struggle to Give Franklin Pierce a Spotlight,” Wall Street Journal, September 14, 2013; available at http://online.wsj.com/article/0,,SB1044919196169723703,00.html

[6] Ibid.

[7] Nate Silver, “Contemplating Obama’s Place in History, Statistically,” New York Times, September 14, 2013; available at http://fivethirtyeight.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/01/23/contemplating-obamas-place-in-history-statistically/

[8] Jamie Frater, “Top 10 Worst US Presidents,” Listverse, September 14, 2013; available at http://listverse.com/2007/11/06/top-10-worst-us-presidents/