For several weeks my local art museum displayed a traveling exhibit from the Johnson Collection of art permanently located in Spartanburg, South Carolina. The prevailing consensus among historians is that the antebellum South did not produce much in the way of art, that its literature was substandard, and that its only contribution to American history was slavery and militaristic oligarchy. Those who read this blog understand this position to be blatantly false, but the opinion still exists.

The important part of this critique, however, is the perception that anything Southerners produced or anything produced about the South in antebellum America is somehow substandard unless it is an open critique of Southern society. Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin: good; William Gilmore Simms’s The Sword and the Distaff: bad; Theodore Weld’s American Slavery As It Is: good; Nehemiah Adams’s A Southside View of Slavery: bad.

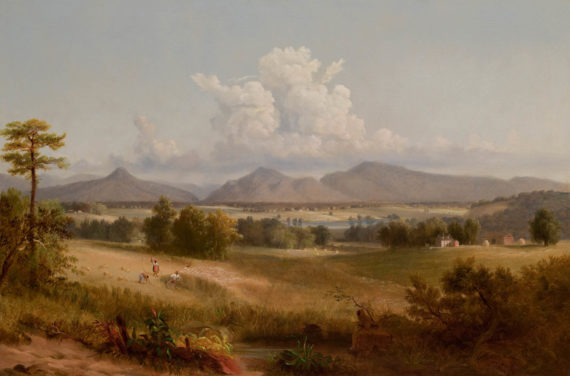

Several paintings in the Johnson Collection stood out, not the least of which was the original Lost Cause by Henry Mosler, but there is one that nicely exemplifies the thinking of the modern historical profession in regard to Southern art, William Thompson Russell Smith’s Shenandoah Valley (pictured above).

Smith was a Northern artist who enjoyed Southern life and often painted sweeping landscapes of the South. Shenandoah Valley is a picturesque landscape complete with several slaves harvesting wheat. The description of the painting includes this gem: “Smith chose to romanticize Southern rural life rather than depicting its harsh realities….Thus, he presents African-American figures in the painting as if they are picturesque peasants working contentedly in an idyllic field rather than as slaves laboring involuntarily for the owner of the plantation home at right.”

Smith could not have been painting what he saw. No. He was making this up so that people would buy his work. This is not an endorsement of slavery, but merely a point that anything remotely benign or positive about antebellum Southern life has to be a product of the “Lost Cause” mentality and needs to be corrected by our wise Northern academy. Forget that Smith painted this in 1846 and that he was a Northerner. That doesn’t matter. It is only sufficient to “correct” an “idyllic” impression of the South and to explain the true harsh realities of Southern life. This type of narrative only serves to compound racial animosity. It has been this way since the antebellum period.

The Johnson Collection includes works by Charles Bird King, stunning portraits Stonewall Jackson and John C. Calhoun, the famous The Burial of Latane, and others. For more on the collection, visit its website.