The finest of gentlemen founded South Carolina, informants assured the famous London Times correspondent, William Howard Russell, upon his arrival in Charleston in April, 1861. “It was established not by witch-burning Puritans, by cruel persecuting fanatics, who implanted in the North the standard of Torquemada, and breathed in the nostrils of their newly born colonies all the ferocity, bloodthirstiness, and rapid intolerance of the Inquisition,” the South Carolinians assured him, shortly after their bombardment of Robert Anderson’s band of astoundingly brave Union men at Fort Sumter. Confusing its own bigotry with Christianity, Puritanism had birthed “impurity of mind among men” and “unchastity in women,” thoroughly enveloping the New England soul, the South Carolinians continued. Evil, corrupt, and dark, Northerners might very well “know how to read and write, but they don’t know how to think, and they are the easy victims of the wretched imposters on all the ‘ologies and ‘isms who swarm over the region.” To a southerner, the North seemed nothing short of decadent, its freedom not standing for anything but a loss of purpose and direction, its people confused, running in many directions, chasing nothing of import. “The parties in this conflict are not merely abolitionists and slave-holders—they are atheists, socialists, communists, red republicans, Jacobins on the one side and the friends of order and regulated freedom on the other,” a famous southern theologian, James Henley Thornwell, had written. “In one word, the world is the battleground, Christianity and atheism the combatants, and the progress of humanity is at stake.” Another South Carolinian minister, Thomas Smyth, claimed the Yankees to be “Bible-haters, anti-christian levelers, and anarchists.” If Puritanism had not caused enough trouble, its unholy allies, capitalism and immigration, had further corrupted the North. “We don’t want to risk our handsome, genteel, educated young fellows against a gang of Irishmen, Germans, British deserters, and New York roughs, not worth killing, and yet instructed to kill to the best advantage,” a South Carolinian worried in January 1861. “We can’t endure it, and we shan’t do it.” Perhaps independence would cost too much, they admitted. “I would not fear so much were our troops to meet the fanatics of the North face to face, for we have truth, justice and religion on our side and our homes to battle for,” Miss Emma Holmes wrote in her diary in February 1861, “but Fort Sumter is almost impregnable and to take it thousands of the best and bravest of Carolina’s sons must be sacrificed.”

South Carolinians had a sense of their own supposed superiority. Some criticized the institution of slavery for giving them this overconfidence. Masterdom made the man believe himself to be a god, the argument ran. A northern college student, E.G. Mason, visited South Carolina in 1860 and saw things differently, however. Several things struck him—the clean streets, the friendly people, and relatively good white and black relations. Mason considered South Carolina to be a true res publica, a place where the best gave their all for the betterment of the community. “The public institutions were admirably managed, and the best citizens gave to these their time and means without stint,” Mason remembered in his 1884 memoir. “Their standard of duty in municipal and state affairs was lofty.” Mason attributed this sense of superiority to the heroic behavior of their grandfathers in the American Revolution. “Their self-confidence was boundless,” Mason wrote. “Their superiority to the citizens of other States was mentioned, not boastfully, but in a quiet and axiomatic way. This was curiously exemplified in their Revolutionary traditions, and in their accounts of the part which South Carolina played in that great struggle.” In late June of 1776, the militia of South Carolina, protected by Palmetto logs, had defeated a British invasion of the harbor. On the same spot where Fort Moultrie stood as of the fall of 1860, a South Carolinian by the name of William Jasper had rushed into the heat of battle to pick up and replant a flag that had been shot down during the British fleet’s attack. Embracing the legacy of Fort Moultrie and Jasper as well as their deeply honored martial traditions, South Carolina served, proudly, as the home to three military institutes.

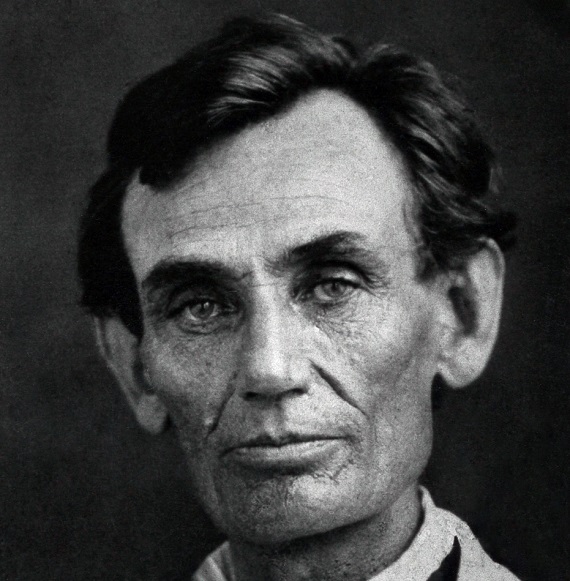

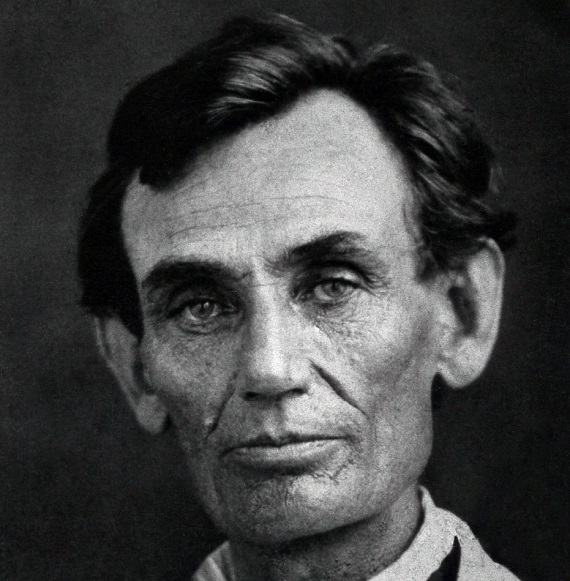

To make matters unbearable to such a proud people, the supposedly hateful, ignorant, and inferior Yankees had recently elected Abraham Lincoln as president. The Republican reflected the worst of northern excesses, South Carolinians at almost every level of society feared. Governor Gist of South Carolina worried that the Republicans under Lincoln would “reduce the Southern States to mere provinces of a consolidated despotism.” U.S. Representative W.W. Boyce claimed that acquiescing to the election of Lincoln would mean certain “death” for the South. Perhaps most electrifying for South Carolina, Federal Judge A.G. Magrath resigned when he received word of Lincoln’s election. He resigned in a very public fashion, giving an address from his bench and departing dramatically from his court house. “We are about to sever our relations with others, because they have broken their covenant with us,” he stated. “Let us not break the covenant we have made with each other. Let us not forget that what the laws of our state require become our duties, and that he who acts against the wish or without command of his State, usurps that sovereign authority which we must maintain inviolate.” J.S. Black, President James Buchanan’s Secretary of State, claimed that Magrath’s resignation greatly shook the sitting president’s confidence, as he believed the entire apparatus of federal patronage and control could collapse as a result of this one prominent and public act of resignation.

Less elite South Carolinians feared Lincoln’s election as well. “’Old Abe’ is on his way to Washington,” one Charlestonian lamented. “He has been indulging in Sundry Stupid, Free love and coercive speeches.” Lincoln, of course, never espoused “free love,” and could be regarded, especially as of 1860, as a conservative and a constitutionalist. But the use of “free love” as symbolic for “radical” and “revolutionary” is certainly telling. Indeed, when many southerners looked north in 1860, they saw not Lincoln, but John Brown. Probably they heard not Lincoln’s generally moderate and conservative words, but instead thought of the praise that well-known northern intellectuals such as Ralph Waldo Emerson had heaped upon Brown as a new saint who will “make the gallows as glorious as the cross.” Emerson was not alone in comparing Brown to Christ. Thomas Wentworth Higginson, who had backed Brown financially as a member of the Secret Six, a New England group of abolitionist ministers, admitted: “Why do you want to know of us? Did any historian ever bother to write down the name of the man who bought the donkey on which Christ rode into Jerusalem? We of the Six were as unimportant and incidental to the real story of John Brown as that ancient Judean is to the story of our Lord.” Further, Higginson argued, the Harper’s Ferry scheme had failed because it was not personal or radical enough. A counter-proposal to this Harper’s Ferry scheme should have been made, Higginson claimed.

While Abraham Lincoln was no John Brown, one can readily imagine why the South felt uneasy about the Republicans, when they were identified with men like Brown and the praise heaped upon him by prominent figures such as Emerson. When future Confederate Secretary of War James Seddon and Abraham Lincoln met during the late winter of 1861 Peace Convention, the former complained: “It is of your sins of omission—of your failure to enforce the laws—to suppress your John Browns and your Garrisons, who preach insurrection and make war upon our property!” The South Carolina government even went so far as to put one of Brown’s pikes on display in the state house in Columbia as a reminder of the fanaticism of the North.

Even those who recognized Lincoln as a good and solid man believed his election to reflect little more than a northern hatred of the South. An anonymous correspondent for the Atlantic Monthly recalled a telling conversation with a Charlestonian. “Is Lincoln considered here to be a bad or dangerous man?” the Atlantic man asked. “Not personally,” the Charlestonian answered. “I understand that he is a man of excellent private character, and I have nothing to say against him as a ruler, inasmuch as he has never been tried.” The president-elect “is simply a sign to us that we are in danger, and must provide for our own safety.” The Atlantic writer pushed the Charlestonian a bit further: “You secede, then, solely because you think his election proves that the mass of the Northern people is adverse to you and your interests.” The response was simple and direct: “Yes.” The South feared northern hatred would turn to coercion at some point in the not-too-distant future. “We don’t trust in the platform; we believe that it is an incomplete expression of the party creed,—that is suppresses more than it utters,” another Charlestonian feared. “The spirit which keeps the Republicans together is enmity to slavery, and that spirit will never be satisfied until the system is extinct.”

Ex-president Franklin Pierce, a Doughface from New England, expressed this fear most articulately, claiming that the election of Lincoln was merely the logical conclusion to twelve years of northern arrogance toward the South. “By letters, by speeches, in private conversation, I have uttered for more than twelve years words of warning against the heresies which have swept over the North and culminated in the enactment of laws which are directly in the teeth of the clear provisions of the Constitution, in eleven states,” Pierce wrote from New Hampshire.

But when you ask me to interpose, then comes this paralyzing fact that if I were in their [Southerners’] places, after so many years of unrelenting agression [sic], I should probably be doing what they are doing. It is not the election of Mr. Lincoln, per se, which has caused this emphatic movement at the South. That election in beyond all doubt Constitutional, but the people of the Southern States look beyond it to see, if they can, what it implies. They see the great and powerful state of Massachusetts electing by 35,000 majority a man who justified the armed invasion of Virginia last year; and they believe that the people of Massachusetts are acting deliberately. They see Mr. Lincoln elected and they take his election as an endorsement of his opinion that we cannot go on as we are, but must in the end be all free or all slave states. Foolish, absurd and groundless as this view is and will always stand, the South takes his election as an endorsement of resistance to the law for the return of fugitives from service of 1851, and of the other heresy broadly promulgated by him and Mr. Seward, referred to above, of an ‘irrepressible conflict.’

Pierce never sent the letter, but he assured his imaginary reader that though he was a Union man, he also believed that “If our fathers were mistaken when they formed the Constitution, if time has proved it, the sooner we are apart the better.”