Jack Hinson’s One-Man War by Tom C. McKenney; ISBN: 978-1-58980-640-5, Pelican, January 27, 2009, 400 pages.

Beheading his sons and impaling their heads on the gateposts of his home – these were the acts of the Yankee liberators of northern Tennessee that somehow upset the ungrateful Jack Hinson in the autumn of 1862.

Jack Hinson was not a firebrand or a man eager for war – and for good reason: He owned over 1,200 acres and many slaves (p34) in Stewart County, near the village of Dover, inside the notch that forms the northern border of the state of Tennessee, along the Cumberland River. He called his home Bubbling Springs. As a matter of prudence, if not inclination, he befriended General Grant (p24) and other Union officers; he opposed secession (p56); and in the summer of 1862, he emancipated his slaves – who nevertheless chose to remain on his plantation (p141).

A Scotsman, Hinson was physically not of the heroic mold, being only 5’5” tall, with long arms that made him look “like Popeye” (p31). However, his character nonetheless revealed itself, according to the following account from Confederate Major Charles W. Anderson, adjutant to Nathan Bedford Forrest, who both became familiar with Hinson:

[His] clear, gray eyes, compressed lips, and massive jaws […] clearly indicated that under no circumstances was he a man to be trifled with, or aroused. [p32]This was the peaceful yet serious man of substance on a collision course with the strategic dilemma confronting Union troops that sought to dominate not just Tennessee, but the vast rural South that did not want to be dominated. Even when not formed into an army, the resentful, uncooperative Southerners presented an insurmountable obstacle to Northern occupation. They would take pot shots at Federal troops, especially at those moving in transports along the rivers – the Cumberland in this case – and then melt away into the woods, earning them the name of “bushwhackers” or, the one used most by William T. Sherman, the name of “guerrillas.” In 1862, Sherman sent frantic notes to his superiors claiming that in Kentucky alone, in order to keep the Union from destruction a minimum of 200,000 troops were necessary – a number greater than the entire Western forces at the height of their strength! (John B. Walters’ Merchant of Terror: General Sherman and Total War, p37.) But the neurotic little Sherman was right: An impossibly large force would be necessary to take and hold any territory in the South by conventional means – “conventional” meaning “respecting the rules of war.” And this was the Northern strategic dilemma: Either admit defeat in holding any significant part of the South, or resort to unconventional war, to a total war where civilians were terrorized with rape and wanton destruction of property, where sustenance for support of themselves and their armies was destroyed, where forced deportations became common, and where all were made to suffer collective guilt for those who did not prostrate themselves with an oath of allegiance to the Northern occupiers. Sherman and indeed the entire Federal high command chose the latter. They slipped off the yoke of discipline on their troops, turning them into rapacious, murderous “bummers.”

Thus the tragedy of two of Jack Hinson’s three sons was laid. George, age 22, and John, age 17, had not joined the Confederacy as their brother William had. There was too much work to do at Bubbling Springs, including hunting game for the family table. And when a patrol of the Fifth Iowa Cavalry came upon them in the woods with rifles in their hands that autumn of 1862, they were stood up and shot (pp150-151). But that wasn’t enough for the nameless commander of this particular patrol. He beheaded the boys, rode around the Dover courthouse square displaying their bloody heads, and finally rode to the Bubbling Springs estate where he impaled them on the gateposts leading up to the Hinson family home (p152).

Whoever he was, he had made the most serious possible mistake of violating a man’s family, and a Southern man’s family at that.

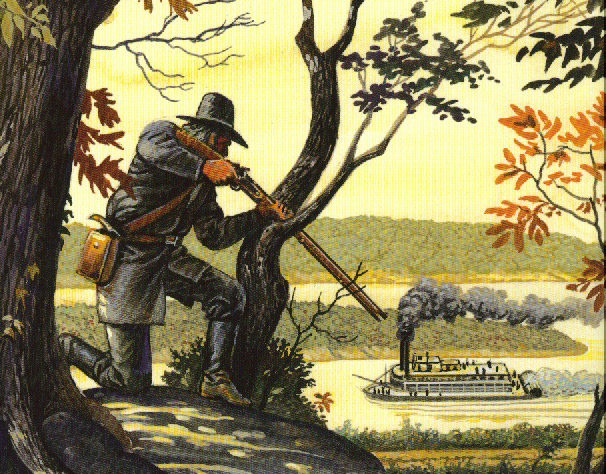

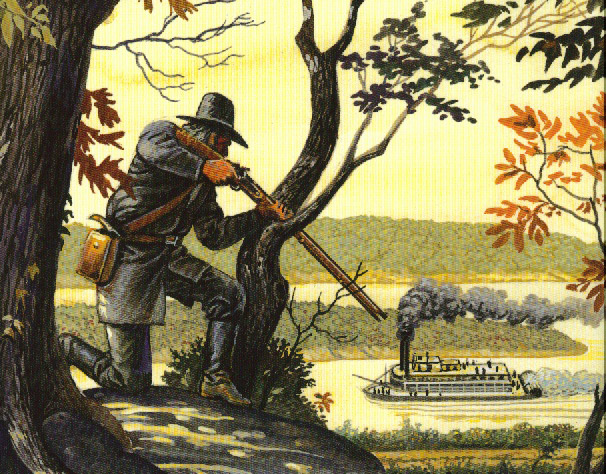

We do not know the details of Jack Hinson’s immediate reaction to the fate of his two sons, but he did not show his anger. Was he too shocked? Were guns trained on him to prevent a response? Or had his anger already forged a heart cold with deadly revenge? We do not know. But we do know that almost immediately thereafter he secretly ordered a weapon of his own special design: The weapon of a sniper. It was a rifle that would “kill more than one hundred members of Grant’s army and navy” (p166, p322).

Here is a comparison of the most widely used two rifles used in the War Between the States with Jack Hinson’s custom made gun:

| Springfield 1861 | Enfield 1853 | Hinson’s gun | |

| Weight | 9 lbs. | 9.5 lbs. | 18 lbs. (a) |

| Length | 40 inches | 55 inches | 41 inches (b) |

| Caliber | .58 Minié ball | .577 Minié ball | .50 Minié ball (b) |

| Max.Range | 620 yards | 1,250 yards* | 900 yards (c) |

| Grains | 60 black powder | 68 black powder | 100 black powder (d) |

(a) p177; (b) p176; (c) p167; (d) p254. * This range may be a stretch, but in any case the maximum, not the effective, is given above. The specifications of the Springfield and the Enfield are from Wikipedia.

The two things to notice is the great weight of Hinson’s gun – double the most popular rifle of the day, the Springfield – and the greater charge of powder. Certainly the two went hand in hand, with the weight reducing the kick from that charge, and steadying the gun for better accuracy.

I will allow you to read of the trials of Jack Hinson’s life, the destruction of his Bubbling Springs estate by Northern soldiers (p234), and the description of many of his avenging kills – almost lovingly described, I daresay, by Tom McKenney, who throughout the book presents himself as an unapologetic Southern partisan. For example, he presents a solid case that slavery was not the issue of the War Between the States (pp44-45), primarily from the fact that Lincoln never pronounced it as a cause and the fact that the institution was common, and indeed original, to the North. He also gives very detailed historical context for conflicts surrounding Hinson’s personal tragedy, particularly the battle for Forts Donelson and Henry in early 1862.

Some may grouse that he has fictionalized conversations and emotions surrounding events in Hinson’s life, but he resorts to this judiciously, with clear enough demarcation of where it is used. There is also some question whether the shock of impact of a bullet can of itself cause death (p257). And it may be noted that it was George McClellan, not Secretary of War Stanton, who called Lincoln the “original gorilla” (p324). These are quibbles in comparison with the absence of the chapter that McKenney was most qualified to write: The chapter detailing the military manual on what is morally right when a commander faces the dilemma of either losing held territory to a recalcitrant populace, or subduing that populace by terror. Most of the command on both sides of the War Between the States went to West Point. Some of Sherman’s and Grant’s subordinates were openly opposed to the methods ultimately adopted by them both. What had they been taught to do?

Nevertheless, praise is due to this book that was more than a decade in the making. Despite a life as a soldier (a U.S. Marine, retiring with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel), Tom C. McKenney proves himself a meticulous scholar who has uncovered probably all there is to know about Jack Hinson, a man who revealed almost nothing of himself through the written or spoken word, or through interaction with more famous contemporaries. McKenney has lifted the mute character of Jack Hinson from oblivion and drawn him as one of the tragic personalities of Southern history.

One Comment