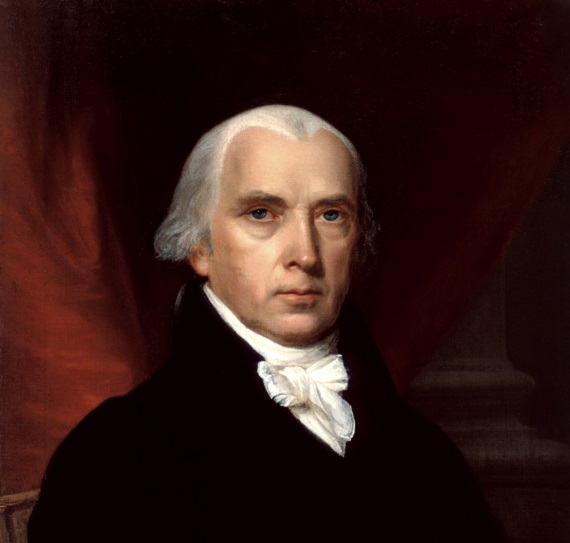

This article will restore necessary context to the word “nullification” as used by James Madison in an 1834 letter called “Notes on Nullification.”

First, we have to put Madison’s role in the formulation of the concept of nullification into some context of its own.

As indispensable as he was to the development of our Constitution, James Madison is not the father of nullification. The idea that a smaller division (a state, a county, a city, etc.) is justified — even obliged — in refusing to obey unlawful edicts of the larger society (the federal government, in the case of the United States) was not original to Madison, Jefferson, or any of America’s Founding Fathers. The doctrine we call nullification was known for generations before the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions were written.

Our Founders drew wisdom and inspiration from a variety of sources, including a group of continental natural law theorists, one of whom was Samuel Pufendorf of Germany (read of the importance of Pufendorf to the Founders here).

In his book The Whole Duty of Man, According to the Law of Nature, written in 1673, Pufendorf explained that for a law “to exert its force,” that is to say, for it to be legitimate, first, the law must be “plainly and openly made.” Can we say that about ObamaCare, the NDAA, the scores of executive orders infringing on the right to keep and bear arms? Absolutely not.

Second, Pufendorf writes that a law may be enforceable only if the subject of the proposed law “belongs to that office” of the lawmaker and it contains “nothing derogatory to the sovereign.”

In the United States, the Constitution is the sovereign law of the land. If, then, any act of Congress (the constitutional lawmakers) exceeds the power given to that body, then the states (Pufendorf uses the term “country or city”) may exercise their natural right to refuse to “pay obedience” to those acts.

Madison makes references to this “right” in his “Notes on Nullification,” the document so often quoted by those who argue that the author of the Virginia Resolution walked back from his support for state nullification of unconstitutional acts of the federal government.

In his “Notes,” Madison attempts to describe “the essential distinction between a constitutional right and the natural and universal right of resisting intolerable oppression.”

The “constitutional right” he speaks of is that being asserted by South Carolina. This is the critically important context mentioned above. In its effort to resist what it deemed federal overreach, the legislature of South Carolina was in fact overreaching itself.

As Mike Maherry of the Tenth Amendment Center explains:

South Carolina essentially asserted that once a single state nullified a federal act, it was annulled within that state and it could not be legally enforced there until three-quarters of the other states overruled the nullification. Furthermore, South Carolina claimed that a state’s act of nullification was ‘presumed right and valid’ until overturned. In other words, a single state could effectively control the entire country.

That’s not the sort of nullification that Madison described as a “duty” of states, one necessary for “arresting the progress of evil.”

In the “Notes,” Madison writes:

But it follows, from no view of the subject, that a nullification of a law of the U. S. can as is now contended, belong rightfully to a single State, as one of the parties to the Constitution; the State not ceasing to avow its adherence to the Constitution. A plainer contradiction in terms, or a more fatal inlet to anarchy, cannot be imagined.

Modern advocates of nullification understand, as did James Madison, that the legislative will of one state is not binding on the others. In fact, a state bill voiding a federal act has no effect on the federal government, either. That is to say, even though a state legislature deems a federal act unconstitutional, that doesn’t make it so, at least anywhere other than in the nullifying state itself.

As constitutionalists, supporters of contemporary efforts to nullify unconstitutional acts of the federal government also demand that the letter of that document be followed precisely.

Therefore, it is important to point out that the Constitution does not permit the government of a single state to render a federal act void on its face or to make it so that the rest of the states must bow to the will of the would-be nullifying state and be forced to refuse to enforce the mandates of the federal act.

This is the application of “nullification” that Madison rightly found constitutionally indefensible.

However, Madison consistently defended the type of state nullification that is “the natural right, which all admit to be a remedy against insupportable oppression.” It would be difficult to argue that James Madison would not consider ObamaCare, for example, to qualify as an “insupportable oppression” worthy of resistance.