At the base of most of the ongoing political debates currently raging in the United Sates there are always, it seems, deeper questions, more philosophical and more historical contexts that need to be examined—what I would call “legacy issues.”

Oftentimes assumptions are made or are disseminated by many self-proclaimed defenders of our traditions—by those “conservative apologists”—that bear little relationship to historical reality, and, in fact, fatally weaken or blur our understanding of it.

Many of these assumptions relate specifically to the conscious creation by the present (neo) conservative movement of a utilizable past that both justifies their present practice and fends off criticism from the hard Left that somehow, because they claim to be “conservative” and presumably defenders of the Constitution and inherited traditions of the country, they partake in forms of “racism,” as well as sexism, homophobia, and white supremacy.

Much of this is motivated by a politics of fear that, I would suggest, comes from the fact that the modern conservative movement, dominated now intellectually as it is by those whose philosophical and fundamental origins are over on the Marxist and Trotskyite left, has never freed itself from the Progressivist historical narrative about racism (=bad) and egalitarianism (=good), and the inevitable “movement of history” (which is always to the Left). It is as if it possesses a guilty conscience and its spokesmen are constantly afraid of being “labeled” racist or some other term of opprobrium.

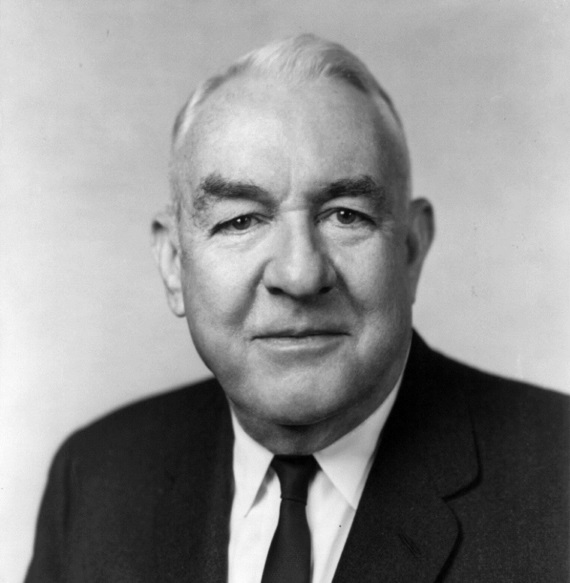

Thus, even though these so-called “conservatives” presume to offer opposition to the “further Left” narrative on various economic and political issues, they are equally possessed by what my friend Dr. Paul Gottfried terms, rightly, a “politics of guilt,” a social sin which they must continually and defensively expiate. And thus, the rather constant, at times frantic, self-justification and strenuous efforts by (neo) conservatives to distinguish themselves from any form or type of perceived “racism.” And, concurrently, their efforts to paint the modern-day Democratic Party with the brush of the odious “historically racist” Democratic Party, and to emphasize the fact that fifty years ago “it was the—mostly Southern—segregationist Democrats who opposed the Voting Rights and Civil Rights Bills.” Then follows a long litany of, again, mostly Southern Democratic political leaders and statesmen—including Senators Harry Byrd (and Robert Byrd), Richard Russell, and Sam Ervin—which is trotted out to “prove” that the Democratic Party just a couple of generations ago was the “racist” party, the party that coddled segregationists…and, yes, that “racist demagogue George Wallace!” Thank goodness, they then add, “we don’t have that legacy!” (Think here, most notably, of the efforts of Dinesh D’Souza, Jonah Goldberg, or Sean Hannity.)

The underlying assumption here is that it has been the Democrats who incarnate historically the evils of racism, sexism, homophobia, and white supremacy—and in some ways, still do—while the clean-as-the-driven-snow Republicans (and [neo] conservatives) have championed equality, opposed racism, supported the Civil rights legislation of the 1950s and 1960s…and, by the way, Martin Luther King Jr, was actually one of them, a dyed-in-the-wool “conservative!”

This narrative in many respects is fraudulent, does serious damage to the understanding of our history, and can be reduced to a form of rather crass political legerdemain, anchored as it is in an acceptance of the Progressivist historical vision. It enables Republican political gurus such as Karl Rove to embrace the neo-Reconstructionist and Marxist posturing of viciously anti-Southern historian Eric Foner, or Sean Hannity to tie in West Virginia’s late US Senator Robert Byrd—who had many years before been a member of the Ku Klux Klan—to Hillary Clinton, or connect Arkansas’s Senator J. William Fulbright to Bill Clinton.

It fails to comprehend dramatic historical change and the evolution of political parties. For much of this nation’s history it was, indeed, the Democratic Party that was most representative of a traditional, Jeffersonian “conservatism.” The Republican Party, founded in the 1850s, not only lacked that essential connection to and understanding of America’s Founding, but in its War-time president, Abraham Lincoln, and succeeding GOP presidents in the second half of the 19th century, incarnated a vision of the American republic that, I would argue, was in many respects contrary to the vision of the Founders. An examination of Lincoln’s views—on statecraft and the powers of the presidency, on the relationship of the various states to the Federal executive, on his faith in unchained financial capitalism, and, indeed, on his view of the Constitution, itself, offer ample confirmation of this.

Obviously, political parties and political thinking don’t remain static. And, especially in the 1930s and beyond, the Democratic Party underwent a transformation. We should not forget that when Franklin Roosevelt ran for president in 1932, his platform was actually, in many ways, more conservative than that of Republican President Herbert Hoover. Only after he entered office did he radically change his praxis.

At first, traditional states’ rights conservatives (e.g., leaders like the Virginia Byrds, and North Carolina’s Josiah Bailey and Sam Ervin) and the more leftwing New Dealers co-existed within “the Democracy,” if uneasily, up through the 1950s. As numerous historians have detailed, the civil rights legislation of the 1960s certainly figured in what would become “the Southern strategy” of inviting disaffected white Southern voters—part of Nixon’s “silent majority”—into the Republican Party.

Yet it would be a major mistake to see “race” as the only causative factor in this process. Indeed, although racial issues certainly existed, larger questions of social, economic and cultural dislocation, the break-up of community, and, above all, the legitimate, well-grounded fear of the loss of local and individual liberties as the Federal government assumed more power and more direct authority over how individuals and families ran their own lives, figured, if not so visibly, even more significantly.

I recall a friend of my father, a well-established farmer and one-time state legislator (the late Democratic State Senator Julian Allsbrook of Halifax County) telling me back in 1968, “I can deal with black folks voting—I will get their votes; but I cannot tolerate in any way the Federal government assuming direct control over practically every aspect of our social and political lives, and making us the new slaves!” I think the good senator’s views reflected quite well those of his fellow Tar Heels.

Making “race” and “racial issues” the only points of discussion—the only determinants for action and reaction—in our history, something that both the Left and the pseudo-conservative Neocons do, leaves out too much that is essential to understanding our complex past.

This first became apparent to me when as a young Jefferson Fellow grad student at the University of Virginia I did research for my MA on the North Carolina Constitutional Convention of 1835 (and conventions in other Southern states). Given the recent (1831) Nat Turner slave rebellion in Virginia, I expected to find a concentration on slavery and the need to defend at all cost “the peculiar institution.” But, rather, I discovered that free blacks with property freeholds had voted in North Carolina prior to that year (and since the Revolution), and that during the lengthy convention debates most of the state’s prominent conservatives –both Democrats and Whigs—defended the suffrage of propertied free blacks. Such notables as state Chief Justice William Gaston, Judge Joseph Daniel, and Secretary of the Navy John Branch under President Jackson, all opposed the change. For these leaders, the issue was not so much about race as it was about class and whether a male elector had the property qualification—and thus the stability, and social and economic status within the community—to exercise the franchise.

There were, of course, a few voices who in their interventions mentioned the Turner rebellion, but remarkably, those views were not overpowering and did not reflect the “white fear” I had been taught by some of my professors to find. In not one recorded peroration did I detect anything approaching the kind of severe racial animus we are supposed to discover in the minds and voices of our ante-bellum ancestors. Even though the convention finally very narrowly voted to eliminate free black suffrage, it is revealing that even at that date, fifteen years after the Missouri Compromise, it was, in a sense, class, social position, and property that still dominated much of the thinking of the dominant political leadership of North Carolina, not race.

Since then, in reading about secession and about slavery as the “cause” of the War Between the States, about the “strange career of Jim Crows,” about the history of the nation’s two major political parties, and then the essentially ideological uses to which the fractured and tendentious template of race—and slavery—has been put, it is apparent that such an approach is fraught with problems. Historians such as Thomas DiLorenzo, Clyde Wilson, Charles Adams, David Gordon, and others have highlighted how the ideological use of such “devil terms” as “race” and “racism” has resulted in a warped view of our past.

Underlying the current “conservative” movement’s anxiety—the fear that Republicans and Neocons have—about being labeled “racists,” then, is the acceptance of the debatable historical “fact” that America is all about race and that nothing else really matters, that severe economic factors, dramatic social and cultural changes, all flow from that single determining issue.

No; give me any day the wisdom, intelligence, devotion to the Constitution—and delightful Southern humor—of a true conservative Democrat, “Senator Sam” Ervin, over the Progressivism and globalist fanaticism of a Republican Lindsey Graham and Jeff Flake, or Neocon Bill Kristol.

That latter narrative I am not prepared, philosophically or historically, to accept.