The Setting

Postcolonial studies have been all the rage for many decades. A great number of contributors to the field have come from India and their work wrestles (in part) with the socio-psychological situation of Indian bureaucrats in the British Raj. These functionaries were, after all, Indians of some kind working for His Majesty’s Government – not the one in London, but His Majesty’s Other Government based in India. Some light is shed on this situation by the Anglo-Canadian historian Edward Ingram (born in India), whose writings on the Great Game – five or more books — are important (and very expensive even as used books).

For our purposes here, Ingram’s main point is this: after losing its thirteen American colonies (or fourteen if we count Vermont, which no one recognized until 1791), Britain compensated for its losses by building a land-based alternative state in India. Both under the East India Company and under the Crown (from 1858), British government in India was largely extra-parliamentary, arbitrary, police-based, and authoritarian — that is, quite a lot like present-day U.S. governance. The Indian government was off-budget, independent for most purposes of parliamentary oversight, had its own bureaucracy and, crucially, its own armed forces. Given Britons’ lack of interest in living in places already heavily populated and many times hotter than Devon, the English Raj had to recruit most of its bureaucrats and soldiers locally, in India.

While it lasted, this meant that the British Empire was, in effect, a Dual Monarchy. There was a British state in the home Islands (England, Ireland) ruling a menagerie of disaffected Celts, Saxons, former Vikings, and Normans — from London. Britain’s second, doppelgänger state ruled India and was able to project power into Burma, the Northwest Frontier (home to so many Afghan wars), South Africa, and even the Western Front in the First European Suicide Attempt (1914-1918).[i]

The implications are quite radical: first, this eastern British monarchy was (as noted) authoritarian, militarist, and illiberal – a sort of bloody-minded Mr. Hyde to the Home Counties’ affable Dr. Jekyll. Second, Colonial Office bureaucrats were largely free to run India extra-constitutionally, a fact that plays Hell with the fashionable “democratic peace” theory. Third, if the Indian bureaucracy and Indian Army are credited to Great Britain, whose upper bureaucrats controlled them, Britain’s “weakness” with respect to the supposed German menace partly recedes into usable fin-de-siècle mythmaking.

Of course arrangements in India could only work as long as the subaltern, native Indian bureaucrats and soldiers kept on taking orders from gents who had gone to English Public Schools and had the right connections. It couldn’t last forever. If you build an effective state full of Indians, one day the Indians will realize they don’t need you.

Apparently, Postcolonialism wrestles with such questions primarily from the standpoint of the subaltern clerks, i.e. the native bureaucrats who stood to gain from independence.

Postcolonialism for Us

I think we ought perhaps to follow this example and look into our own immediate postcolonial situation in British North America, even if the cases are rather different. We too were colonials, but also settlers who meant to stay — the very folks who didn’t flock to India. Like locally-born Spaniards and Portuguese in Latin America, we were creoles, of the same origin and language as our imperial rulers, and like the Latin creoles, not often invited into the upper ranks of colonial administration. In any case, the British administration had grown negligent down to the Seven Years War, or French and Indian War (1755-1763). This was perhaps a mistake.

Having been neglected, the North American colonies learned to solve their own problems and, as historian Jack P. Greene has massively shown, their colonial assemblies (the lower houses) became very assertive, putting themselves very nearly in the place of the British Parliament. Britain’s attempt, from 1763, to head off this obvious trend toward local independence brought on a crisis. Rumors in some colonies that uncollected quit-rents were to be called in — with decades of arrears to pay! – did not help the colonial mood. We weren’t very good subaltern clerks and perhaps failed to understand that we were meant to be such.[ii]

Of course these North American colonies were inwardly riven. We had a class of people close to the British governors and aspiring to be like them. During our Revolution, some of them became Tories, while others joined the right wing (so to speak) of the revolutionary coalition and expected to take power when it was all over. Later they became Federalists and nationalists and endlessly asserted their fitness to rule. But alas, they had no place from which to rule – a problem they solved by lumbering us with their idea of a constitution. Filling up the new offices, from President to Senators and Congressmen to federal (and Federalist) judges, they wrote self-laudatory books and pamphlets in their spare time.

It is little wonder, then, that so many of us even today think of them as wonderful ffounders and fframers. (In the Republic of Letters, we are what we read.)

We might beg to differ. But how can we differ, if we can’t be bothered to read our own colonial and postcolonial sources – without, that is, finding facts on the ground that might (and do) contradict the narrative spun by our supposedly natural, “national” rulers? In this spirit and to this end, let us now turn to the constitution of one of the thirteen former colonies that proclaimed itself a state – a constitution in force during the supposedly incompetent and life-threatening rule (or non-rule) of the Articles of Confederation. I shall not yet name the particular state.

A North American Postcolonial Constitution

The constitution to be discussed is a good example of the form. Ratified in 1780, it slightly preceded the actual coming-into-force of the much-abused Articles of Confederation. It is chockfull of high-flown political philosophy, republican rhetoric, Lockean social contract, and practical detail. I propose to highlight key points of this constitution in a stream-of-consciousness manner. I shall be using here the draft constitution of 1799, since the final constitution adopted in 1780 only differed from the draft in two minor points.

Social Contract

The constitution describes the state as a “body politic” founded on a “social compact”; it was “a voluntary association of individuals” undertaking to “be governed by certain laws for the common good.” “All men” were “born free and independent” but had a duty to worship God. The people of the “commonwealth” constituted a self-governing “free, sovereign, and independent state” with every right and power not “expressly delegated” to the United States in Congress assembled. (Both “expressly” and “delegated” need to be savored here.)

Citizens’ Rights

Government was to be accountable and elections regular. Legal remedies would exist for injuries, and the subject “cannot be held to accuse himself, or to furnish evidence against himself.” No subject could be seized or deprived of property or life but by the “judgment of his peers” and the law of the land – a provision lifted directly from Magna Charta.

The subject was to be “secure from all unreasonable searches and seizures of his person, his houses, his papers, and all his possessions. All warrants, therefore, are contrary to this right, if the cause or foundation of them be not previously supported by oath or affirmation,” and if the order to search “be not accompanied with a special designation of the persons or objects of search, arrest, or seizure…”

It bears mentioning that the two provisions corresponding to the later federal Fifth and Fourth Amendments (or part of the Fifth) enjoy clearer wording here than we find in Mr. Madison’s micro-managed versions.

The constitution also affirmed trial by jury, freedom of speech and press, the right to keep and bear arms in defense of the commonwealth, “frequent recurrence to fundamental principles of the constitution,” and freedom of assembly.

Form of Government

The legislature was to be bicameral: a Senate and House of Representatives. There would also be “a supreme executive magistrate” chosen annually — the Governor. In his oath of office, he would swear as follows: “I will faithfully and impartially discharge and perform all the duties incumbent on me, as governor…”

Note how the absence of abstract “executive power” said to be “vested” in someone (U.S. Constitution, Article II) disallows the speculations of people like John Yoo. Even better, this Governor just performs his duties, instead of “executing the office” (another mighty source of later violent abstractions).

The Governor was to be commander-in-chief of the army and navy of the state, and here things do take an odd turn. In war, he was to meet the enemy: “to encounter, expulse, repel, resist, and pursue, by force of arms … and also to kill, slay, destroy, and conquer, by all fitting ways, enterprises, and means whatsoever, all and every such person and persons” who should seek to invade or destroy the commonwealth.

We were not expecting a worked-out Total War doctrine in a late 18th-century American constitution.

Regaining its composure, the constitution takes up the office of Lieutenant Governor, the executive council, various oaths and offices of a routine nature, and the court system. The constitution confirmed Common law and English statutes as adopted in the colony, along with the writ of habeas corpus.

The constitution also provided for a university and the “encouragement of literature.”

What State Was This?

We could match our mystery constitution’s republican boilerplate (so to speak) and social contract language to that found in almost any post-colonial state constitution. They all went in for that.

But the assertive state sovereignty, bordering on self-absorbed local nationalism – what accounts for that? Can it be a Southern state, perhaps South Carolina? One might almost think so, but the somewhat theocratic tone, the outburst of total war rhetoric, and proposals for a university and aid to literature suggest otherwise. Indeed, these are essential clues.

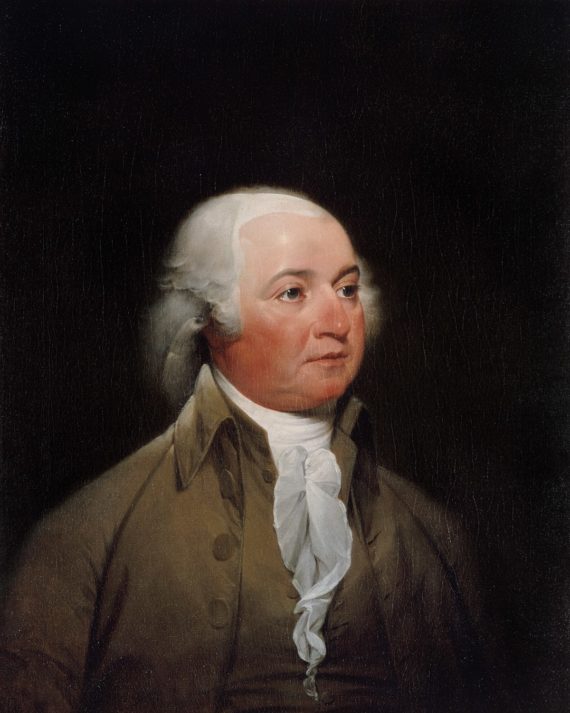

It was in fact Massachusetts and most authorities credit John Adams as the chief (or sole) author of the state’s 1780 constitution.[iii]

The Flexible New England Mind

What can this possibly mean? Well, for starters, it seems to mean that the same political actors could harbor a fierce commitment to the sovereignty of their own state while at other times working to extend their leadership and ideological-economic system over their co-states.

Adams himself illustrates the point nicely. In his third Novanglus Paper in 1774, he refers to the “the cordial, firm, radical, and indissoluble union of the colonies,”[iv] referring only to the unity of opinion in the colonies with respect to English policy, and not to any political arrangements among colonies that had not yet even declared independence. After independence, in the preliminary discussion of Articles of Confederation on August 1, 1776, Adams declared: “That the individuality of the colonies is a mere sound… The confederacy is to make us one individual only; it is to form us, like separate parcels of metal, into one common mass.”[v]

Yet as we have seen, the same Adams could write a constitution for Massachusetts in 1799 that hardly acknowledged the existence of the Confederation.

In the end – with the exception of the Hartford Convention of 1814 – Massachusetts and New England statesmen increasingly set their sights on domination of the union. This quest for the ring of power had its consequences, as Lewis P. Simpson puts it, such that “the moment of the New England nation’s victory over the southern nation was in truth also the moment of the defeat of New England.”[vi]

Postcolonial Studies appear to be both essential and perilous. Lasciate ogni speranza, voi ch’entrate.

[i] Edward Ingram, “Hegemony, Global Reach, and World Power: Great Britain’s Long Cycle,” in Colin Elman and Miriam Fendius Elman, eds., Bridges and Boundaries: Historians, Political Scientists, and the Study of International Relations (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 2001), 223-251.

[ii] After winning our independence, we cultivated a national style of bumptiousness, in contrast to the Australians who developed their famous Cultural Cringe.

[iii] “The Report of a Constitution, or Form of Government, for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts,” in

- Bradley Thompson, ed., The Revolutionary Writings of John Adams (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2000), 295-322.

[iv] Revolutionary Writings of John Adams, 169.

[v] Quoted in Thomas Jefferson, “Autobiography,” in Paul Leicester Ford, ed., The Works of Thomas Jefferson, I (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1904), 53.

[vi] Lewis P. Simpson, Mind and the American Civil War: A Meditation on Lost Causes (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1989), 73.