There was a little dog down the street from us named Streety. My brother and I hadn’t got our own dog yet; that was five or six months in the future. So, we had adopted Streety as our own–though many in the neighborhood had done the same. He belonged to an elderly gentleman (I think he was about 80, though as a six-year-old, it was difficult to guess ages) down the street named Mr. Worley. My mother said Mr. Worley’s wife had died the day after I was born and Mr. Worley had taken Streety in shortly afterwards.

Streety was all over the neighborhood, a friend to all, a large mutt of mixed ancestry. All of this was typical of small town Southern life. Not that Yankees didn’t have small towns, dogs or friends, but they weren’t stranger oriented, as they were more interested in what you did (money) as opposed to where you were from (family). Besides, Yankees don’t love dogs as much as they prefer to kick them. But I’m a bit away from the story.

Streety was friendly and dirty: both most of the time. He loved the drainage ditches in front of the houses and when it rained he was in Hog Heaven. Often in the summer we would join him in the water-swept ditches, attempting to ride on his back (his mixed ancestry had some big dog in him) down to the end of the street where the ditch emptied. A day later after the water subsided we would spot Streety back in the ditch, enjoying the mud—this was from Hog Heaven to Pig-in-Slop. My mother allowed us the first but not the second, though she had, in a minor way, adopted Streety, too.

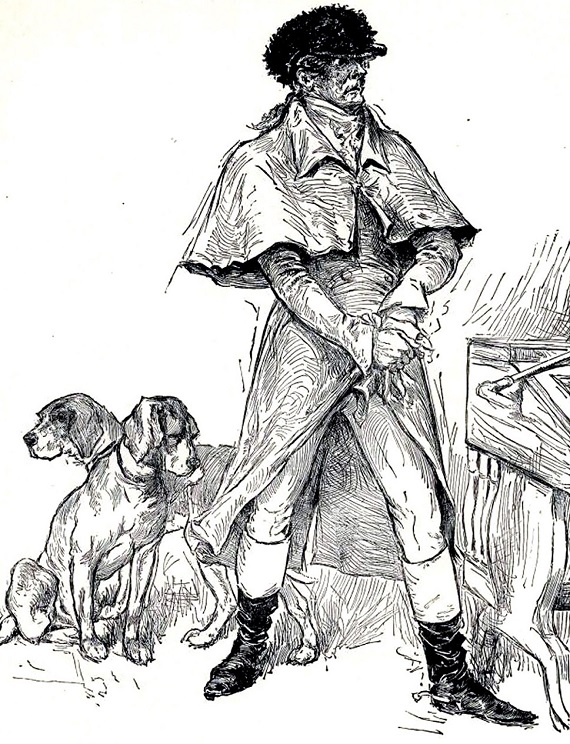

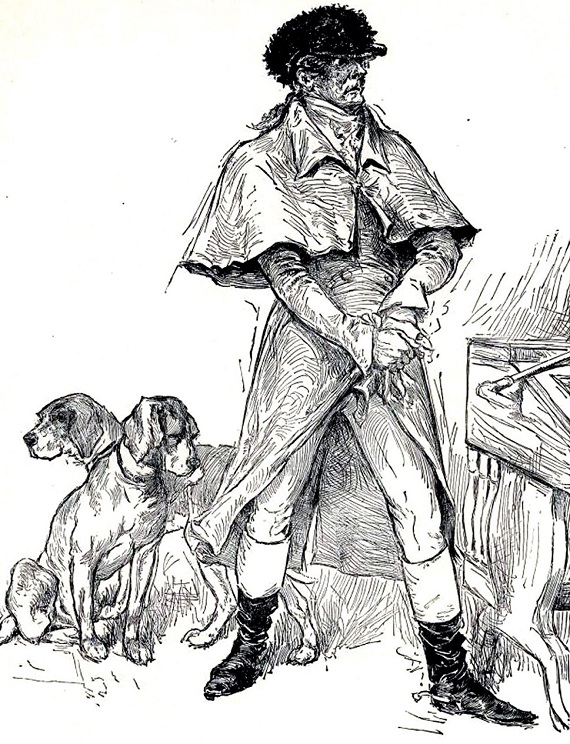

Streety sure loved Mr. Worley. We often saw Mr. Worley walk out onto his front porch and spread his arms as Streety bolted toward him, his front paws landing on the top of Mr. Worleys shoulders. Mr. Worley would turn his head to one side in order to avoid the face-on-slurp and lick. After a moment, Mr. Worley would sit in his chair and Streety would gather his 90 pounds or so at his feet, content just to be there, while Mr. Worley smoked his corn cob pipe. He was the only man I ever actually saw smoke a corn cob pipe in person.

Streety was so friendly and could size people up quickly that our neighborhood mailman actually brought Streety treats from time to time. Often Streety followed the mailman on his rounds, as if he were protecting him from some growling stray that might be about.

One day Streety was killed. A truck driver speeding down one of the neighborhood streets hit him broadside. He lay there bleeding from the mouth, his crumpled body twitching. But my friends and I knew the twitching was not a sign of life but of the end. We cried as much for Mr. Worley as for Streety I think. Mr. Worley walked slowly toward the street, his deliberate steps a sign he too knew Streety would never stand or run again. And we saw Mr. Worley rub his eye with the back of his hand. It was the first time I had seen a man cry.

As I got older I was to look back and remind myself that this was something coming to the South that would change its character to some extent. Cars and trucks racing through neighborhoods was not localism, not Southern.

I don’t know why, but though I saw Mr. Worley on the porch after that, I never again saw him smoke his pipe. My mother said that maybe he had quit smoking.

I thought maybe he had just quit.