Our culture has, of late, become rather fixated on the idea that every historical figure in our past should have anticipated how moral worldviews would evolve after his or her death. Now, clearly, this is impossible. Picasso and Hemingway, to take two great artists who were also generally terrible people, could not (and should not) have thought about how their work would be viewed decades hence. To do so would have made for rather less interesting work—art in the service of popular opinion, rather than art in the service of art.

Not that this distinction matters to contemporary progressives, who have embraced a peculiar cultural quest: whitewashing our history and purging it of anyone who did not conform with contemporary moral standards. This has led to what we might call the Great Erasure, which is an attempt to “correct” the allegedly benighted views of the past and “align” our culture with our new and “improved” moral standards. Thus the tearing down of monuments, the attempt to erase people like Bill Cosby from memory, and the insistence that art and history should always and everywhere be in the service of that most nebulous and vaguely defined of crusades: social justice.

This is rubbish, of course, and is nothing more than a dressed-up version of the Whig theory of history, but it seems to be terrifically persuasive rubbish. This is especially true in my hometown of Columbia, MO, where on May 14 Robert E. Lee Elementary School was officially renamed “Locust Street Expressive Arts Elementary School” by the Columbia Board of Education. (The school sits on Locust Street near the campus of the University of Missouri.) If that names strikes you as a mishmash of meaningless progressive buzzwords, well, you’re exactly right. The coverage in the Columbia Daily Tribune notes that there were “passionate arguments for and against the change,” but in the age of the Great Erasure the change was always a foregone conclusion.

Parents and citizens who spoke in favor of the name change argued, among other things: that naming a school after Lee was simply “preserving a legacy of white supremacy in this town”; that the name did not reflect the “diverse student population”; that “the man whose name is over the door fought to preserve slavery”; that the name “excited strong feelings and doesn’t promote welcoming and access”; that changing the name would “help the school be a more inclusive place for all students”; and, perhaps most oddly, that the change was needed to help “students to prepare for the future.”

Well. One can only imagine how difficult it has been for students to attend school in a building whose name “excited strong feelings.”

We could pick these arguments apart one by one, of course. We could explain Lee’s oft-noted abhorrence of slavery, for example, or expose the inherent hollowness of an “inclusion” that explicitly seeks to ban opposing views. We could note that the War was rarely as cut-and-dry as we’d like to think, or point out that labeling Lee a symbol of “white supremacy” reveals a shockingly shallow understanding of Lee, of supremacy, and of general history. But all these rebuttals require a firm grasp of nuance and, well—the Great Erasure brooks no nuance.

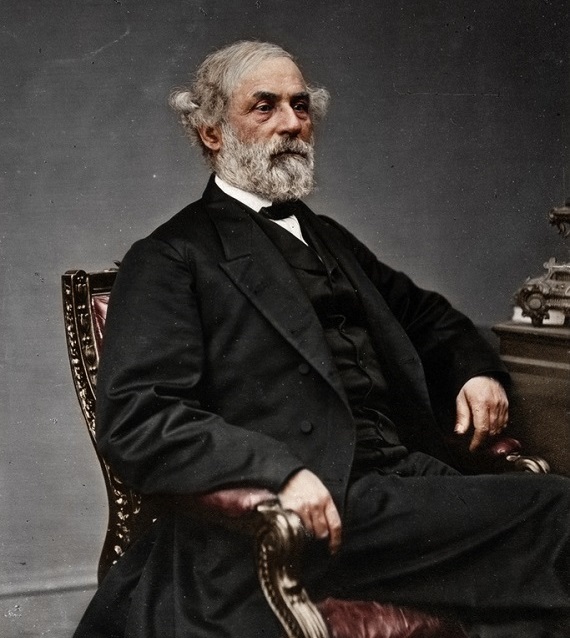

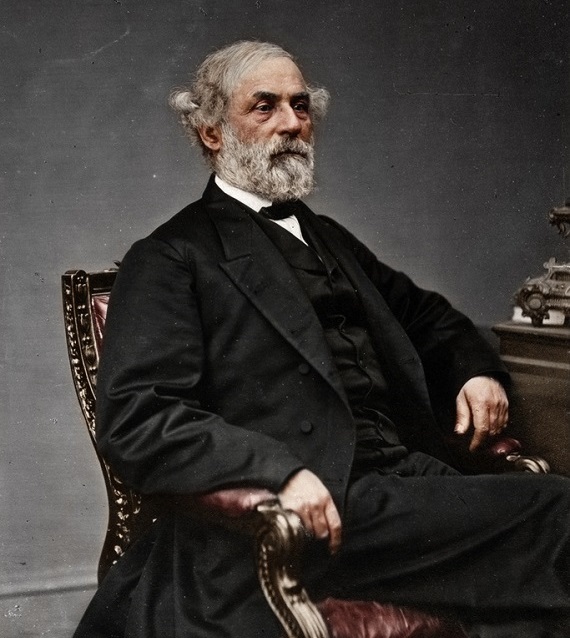

Being a native Columbian and a general admirer of Lee, the closest approximation we have of an American Seneca, I have followed the developments with some interest. It has been useful during all the Sturm und Drang to revisit the essay “Lee the Philosopher,” by Richard Weaver—the great midcentury man of letters and frequent chronicler of Southern history and culture.

Weaver’s essay, published in the Georgia Review in 1948, seems depressingly prescient when he writes that people have always attempted to project their own agendas onto the stoic Lee. Because “the keynote of Lee’s character was simplicity,” and because Lee usually declined to discuss the War in hindsight, and because it “has proved tempting to picture him as a somewhat passive embodiment of the culture of his region,” we tend to make Lee into whatever our current culture wants him to be. He has become a kind of cultural palimpsest, with generation after generation rewriting his history and erasing what came before.

It must be maddening to those conducting the Great Erasure that Lee himself remained so silent on so much. Weaver notes that a central theme for Lee was “the counsel of patience and silence.” In what might be a description of the current debates over monuments and statues, Weaver writes that Lee “knew that the mind of a people at war is psychopathic, that it is subject to hysteria and hallucination, that often it cannot tell right from wrong or even friend from foe, that it is likely to prefer revenge to survival.”

Is this not what is happening now? Taking Lee’s name off a school building is a form of revenge: against history, against nuance and context, and, alas, against historical accuracy and deeper understanding. The forces of the Great Erasure have power, and as Weaver writes, “the touchstone of conduct is how one wields power over others.” They could have chosen inclusion; they could have chosen understanding and discussion. They chose revenge instead.

There is a wonderful quote from Goethe: “How can man learn to know himself? In the measure in which thou seekest to do thy duty shall thou know what is thee. But what is thy duty? The demand of the hour.” We become the people we are by our willingness to do what is demanded of us, even if we do not like it. Perhaps this includes discussing the less than rosy parts of our shared past in the name of true education. Lee, of course, famously believed duty to be the most sublime word in the language. Weaver called this Lee’s “tendency to see a thing in its moral relationships, to discipline the egoistic impulse, and to subordinate self to a communal ideal of conduct.”

Our current culture has neatly flipped this on its head. We are all egoistic impulse; we are all glorification of self. This is the dismal reign of identity politics, in which a student can be irreparably harmed, it seems, by simply seeing a name above the door which “excited strong feelings.” Perhaps Weaver is right that “the mind of a people, like that of an individual, may become so deranged with anger that it is simply not receptive to the realities. Because this psychopathic mentality cannot interpret objectively, it does not want to hear reason and may be offended by a proposal in proportion as it is reasonable.”

What we call identity politics Weaver called “sentimental humanitarianism,” which “manifestly does not speak the language of duty, but of indulgence [and believes] that obligations are tyrannies, and that wants, not deserts, should be the measure of what one gets.” To believe this is to place mankind in too central a role, and is to ignore the plain fact—understood by Lee, by Weaver, and by many millions of others—that “mortal wisdom is not to be compared to infinite wisdom… To assume that [man’s] light is always sufficient is pride.”

If the Board of Education had truly wished to educate, the members would have borne in mind this thought from Weaver: “Fully interpreted, Lee’s ‘duty’ is the means whereby freedom preserves itself by acknowledging responsibility.” Had Lee’s name been kept above the door, the school could have used it as a wonderful tool for acknowledging responsibility, and thereby for preserving freedom. Yes, they could say, we Americans have done terrible things in our past. No, we still aren’t sure how to balance our historical errors with our achievements. Yes, we used to cherish the memories of men we might now see as less than great. No, that does not give us the right to erase our shared cultural legacy. We all must live with what we have done. Erasing a monument does not erase the event that inspired it.

Alas, the students at the Locust Street Expressive Arts Elementary School will hear none of this. They will hear no word of the man who said that “Human virtue must be equal to human calamity.” They will study only the men and women we consider today to be winners, with no awareness that in a generation or two we will come to believe something else entirely—and the Great Erasure will begin anew.

We cannot rewrite the past any more than we can forget it. No wonder Weaver wrote that Lee’s postbellum mien was one of “settled sadness.” He saw, even as early as 1866, how people were trying to categorize him, pigeonhole him, label him. What a pity that a whole generation of students will know Lee not as a complex man, not as a nuanced man, and not, like all of us, as a flawed man. They will know him only as the man who was erased.